[ad_1]

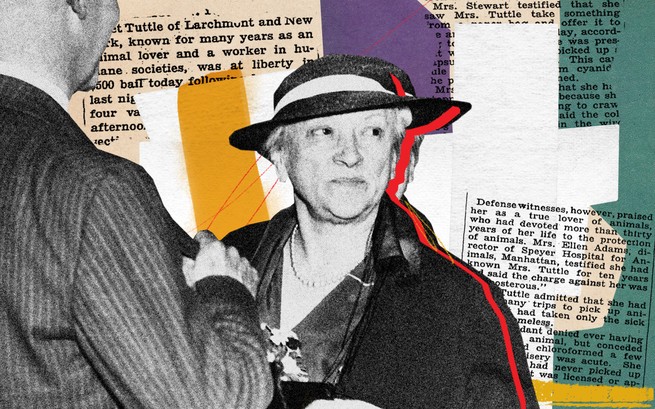

In a ritzy Park Avenue condominium, Juliet Tuttle posed in entrance of a birdcage, staring into the eyes of a parrot. She wore a sublime silk gown and a cloche hat. A photographer snapped an image, and shortly Tuttle appeared in newspapers across the nation underneath the headline “Not Afraid of Parrot Disease.”

The yr was 1930 and a panic had erupted over an sickness unfold by birds. Though just a few hundred Americans had caught the flu-like “parrot fever,” individuals have been so afraid of being contaminated that they wrung the necks of their very own pets. Tiny carcasses piled up in trash cans, the good blue-and-green wings mendacity limp among the many coal ash.

Tuttle insisted that the fears of contagion have been overblown, saying that she usually kissed her birds on their little beak. She appeared just like the form of daffy, kind-hearted widow who would at some point depart her fortune to her menagerie. And but seven years later, a tabloid dubbed her the “Eastchester Dog Poisoner” after she was caught in a New York suburb doling out suspicious tablets in doggie treats.

When I stumbled throughout an previous newspaper merchandise about Tuttle’s trial, I used to be drawn in by the paradox: Tuttle had been a widely known advocate for animals. Why would she have killed canine in such a ugly vogue? Eventually, I pieced collectively clues that had remained hidden for nearly 100 years. And that’s how I realized that Juliet Tuttle might have been essentially the most prolific pet killer on this nation’s historical past, an angel of loss of life who not solely poisoned canine but additionally hunted cats by means of the streets of New York City, bagging them up and snuffing them out.

As I write this, the Bowen Road Dog Poisoner is stalking the parks of Hong Kong, scattering meat laced with pesticides—the mysterious assaults have gone on for greater than 20 years, with no break within the case. It’s not taking place simply in Hong Kong: Dog poisoners are all over the place. In Berlin, individuals have been taping up indicators on bushes, telling tales of canine which have died in agony. And in Melbourne, canine homeowners have been just lately suggested to maintain their animals inside due to a rash of poisonings.

When I used to be a child in Maryland, a neighbor’s German shepherd ate a chunk of steak that somebody had thrown within the yard. The candy previous canine drooled for hours earlier than he died in convulsions. Soon different neighbors discovered lumps of meat of their yards too. Looking again now, I understand that my mother and father weren’t apprehensive a lot concerning the canine as they have been about us youngsters. “If you see anything in the grass, don’t touch it,” my mom lectured me, time and again. All that summer season, a low buzz of worry electrified the boggy warmth.

Dog poisoning isn’t simply concerning the canine. Somebody is sending a message: “It’s so easy to kill. You or your kids could be next.” The assaults can infect a whole metropolis with paranoia. Even so, pet poisoning is a little-studied crime. So who’re these criminals? And why do they do it?

The case of Juliet Tuttle gives some clues.

One spring day in 1937, Tuttle stepped out of her limousine in Eastchester, New York, and crept as much as two canine taking part in in a area. She extracted a small paper bag from her pocket and fed the canine by means of a fence. All the whereas, her personal canine, a Boston terrier carrying a inexperienced sweater, waited within the limousine.

A witness named Mrs. John Stewart noticed this unusual scene from a bus cease throughout the road. Hours later, a type of canine was useless and the opposite, violently unwell. And Mrs. Stewart’s personal Irish setter had died in her yard. Mrs. Stewart informed the police that she feared that anybody who would poison canine may additionally feed arsenic to the neighborhood kids.

Police detectives traced the limousine to a rustic dwelling in Larchmont and introduced the proprietor, Tuttle, and her chauffeur in for questioning. The chauffeur mentioned that he squired Tuttle out for drives round Westchester County every single day to feed canine. On the Saturday of the poisonings, he had pushed his employer round Eastchester and Edgewater Point in Mamaroneck. The police had acquired stories of sick and useless canine alongside that route; an English sheepdog that belonged to a girl in Edgewater was in important situation, and two different canine had been discovered floating in Crestwood Lake, close to Tuckahoe.

As the our bodies piled up, much more pet homeowners got here ahead with tales of mysterious deaths and disappearances. In the previous couple of months, the Eastchester Police Department had acquired stories of greater than 75 canine that had been poisoned or gone lacking. Suddenly all of these disconnected disasters shaped a sample, and the clues led again to the girl within the limousine. Police discovered a gelatin capsule close to the fence the place she fed canine; it contained cyanide.

And but Tuttle, “with flushed face and a harassed look in her eyes,” one account learn, protested to the police chief that she had “never poisoned an animal in her whole life.”

In reality, a number of years earlier than, Tuttle—then a high-ranking member of the Women’s League for Animals—had sounded the alarm a few supposed plague of cats swarming the streets of Lower Manhattan. She had bragged to the press that she had developed a system for capturing strays, bagging them up and executing them. At that point, she’d been going underneath her late husband’s title—Mrs. Charles A. Tuttle of Park Avenue. But in 1937, she was generally known as Juliet Tuttle of Larchmont. Perhaps nobody realized that the 2 Mrs. Tuttles have been the identical individual. As I pored over articles concerning the case, it appeared to me that none of her accusers had linked the dots between the Eastchester Dog Poisoner and the Mrs. Charles A. Tuttle who had devoted herself to the “mercifical” extermination of avenue cats.

I had questions, and I needed to carry them to the consultants. I wasn’t capable of finding any intellectuals who specialise in pet poisonings, so as an alternative I consulted with Deborah Blum, a journalist who has written extensively about human poisonings. Blum informed me that individuals who kill with poison are demographically completely different from most different killers—they’re extra more likely to be feminine. “Think Arsenic and Old Lace,” she mentioned. When girls homicide, “they choose poison about seven times as often as men,” she mentioned. And that is one purpose poisoners can evade detection—they are typically the great little previous girls whom nobody suspects.

Blum mentioned she thought the identical sample was more likely to apply to animal poisonings. Certainly nobody anticipated Juliet Tuttle, the self-professed animal lover, to have dedicated these crimes. When she was placed on trial in 1937, a reporter summed up the shock over the Eastchester Dog Poisoner turning out to be a decorous previous girl: “The accusation seemed so preposterous it was almost funny. Of all the men, women and children in the United States,” it appeared that “this nice old woman was the last person in the world who would hurt any animal,” and that “the authorities at Eastchester, NY, must be crazy.”

In her early 30s, Juliet had married Charles Tuttle—a Yale man who had based a New Haven newspaper and labored as a reporter earlier than falling unwell. Less than two years after the marriage, Charles died of tuberculosis. With her husband out of the image, Juliet reinvented herself as a social climber in Manhattan. She moved right into a Park Avenue condominium, summered in Westchester, and employed a dressmaker, maid, and chauffeur. She rose to prominence in New York animal-rights societies, showing in newspapers underneath the title Mrs. Charles A. Tuttle as a buddy to birds, utilizing the parrot-fever panic to vault herself into the general public eye.

One of her closest associates was one other widow, Helen—Mrs. George Bethune Adams—who ran town’s largest animal hospital. The New Yorker described Adams as a “spry, reticent lady who favors old-fashioned black serge dresses and Queen Mary hats.” Tuttle was many years youthful than her buddy, however she started dressing in the identical sober, vaguely British vogue. In the black costume of a grand dame, she grew to become a frontrunner within the New York Women’s League for Animals.

Cats had all the time been an important a part of town’s ecosystem, holding down the rat and mouse populations. And but in 1931, a newspaper reported that Tuttle had declared that town was “suffering from a plague of homeless, half-starved, abandoned cats, carriers of disease and a disgrace to humanity.” She painted an image of a furry tide that threatened to engulf town and solid herself because the compassionate euthanizer. She informed reporters that she spent “six days a week and about nine hours of each day” using round behind her limousine in an effort to scoop up “all the stray alley cats and homeless dogs she can find and [take] them where they receive care or merciful destruction.” With what seems like relish, she shared her technique for knocking out the cats: “She carries onion bags in her automobile,” the report acknowledged. “These bags she soaks thoroughly in catnip water before she starts on her tours. Once inside a bag, the cats were “bound for oblivion.”

Of course, catnip wouldn’t really knock out a cat. Tuttle would finally admit that she used chloroform. “The cats come out in great numbers at night,” Tuttle informed reporters attending a Women’s League for Animals assembly, “but even in the daytime I can find enough sick, injured and starving cats to fill the baskets in my car.”

Even as she launched herself as an officer of a company dedicated to defending animals, she was breaking a lot of the metropolis’s anti-cruelty legal guidelines. You definitely weren’t allowed to chop the lock on a door to somebody’s home or store, sneak into their property, and abduct all their cats, earlier than tossing them into the loss of life chamber on the Ellin Prince Speyer Hospital for Animals, New York’s first free animal hospital.

If you had been strolling down Lafayette Street in Lower Manhattan within the Thirties, you’d have marveled at that hospital, a five-story palace devoted to lavishing each kindness on pets. Walk by means of the entrance door—underneath the gilded signal that learn Women’s League for Animals—and up the steps, and you’d glimpse an working room custom-designed with a raise for horses. On the roof, a glass-domed room allowed canine to bask within the solar as they recovered from distemper. Also on the roof: the chambers the place the terminally unwell or harmful animals may very well be given a fast loss of life.

Tuttle operated proper out in plain sight, at a time when New York City had essentially the most superior animal-protection legal guidelines within the nation. The canine catchers of the previous had been abolished many years earlier. The New York Times explained a brand new animal-control legislation, generally known as Chapter 115, again in 1894: Strays could be put up for adoption and positioned in properties, whereas a number of “worthless” canine and cats—these too sick or aggressive to be pets—could be “put to death in as humane a manner as possible.”

The legislation put town right into a paradoxical bind: Now that it was unlawful to beat a canine to loss of life on the street or dump cages stuffed with stay animals into the East River, somebody needed to take accountability for the strays that couldn’t be adopted. And so animal-protection teams started pioneering the concept of a merciful or painless loss of life as one of many antidotes to struggling. When the canine or cat couldn’t be rehabilitated, it will be zapped by electrical energy, drugged to loss of life, or snuffed out in a fuel chamber. To common New Yorkers, this might have appeared like a cleaner, extra humane decision. But nonetheless, one imagines, they didn’t very similar to to consider the killings themselves. Groups such because the Humane Society and the Women’s League constructed execution chambers and hid them away, the place the general public would by no means see them.

A brand new concept was being invented within the twentieth century: that loss of life may very well be a medical process. It was the start of a dialog about physician-assisted suicide for individuals and a merciful loss of life for animals. In the Thirties, American euthanasia societies started pushing for legal guidelines that might give terminally unwell individuals the correct to die. It was each a really trendy concept and but additionally, from the beginning, twisted up with the racist and ableist concepts of the eugenics motion.

Into that new ethical twilight got here Mrs. Charles A. Tuttle, a.ok.a. Juliet, a.ok.a. the Eastchester Dog Poisoner.

When I described the Juliet Tuttle case to Deborah Blum, she mentioned Tuttle appeared like an “angel of death”—just like the form of serial killer who preys on (human) hospital sufferers. These killers usually use poison—or overdoses of medicines—as their weapon, they usually cover within the area between mercy and homicide. An instance: Donald Harvey claimed that he started nudging terminally unwell sufferers towards loss of life within the Seventies at a hospital in Kentucky the place he labored as a nurse’s aide as a result of, he mentioned, he hated to see them endure. Then, it appears, he grew to become so hooked on the ability rush that he bought from killing that he started concentrating on dozens of sufferers—and likewise poisoned his lover and a number of other neighbors. His yearning for the kill escalated. In 1987, he pleaded responsible to murdering 37 individuals, a lot of them by arsenic and cyanide poisoning.

Similarly, Juliet Tuttle represented herself as an angel of mercy who killed in an effort to stop animals from struggling. And she, too, grew to become extra reckless as time went on.

She started by abducting cats from speakeasies, resorts, and tenements—animals which may loosely be known as strays. Then she started to focus on pets. In 1934, a Brooklyn lady took Tuttle to court docket, accusing her of abducting a tabby named Topsy. Tuttle admitted to the choose that she had responded to an advert providing Topsy’s kittens for adoption; she mentioned she had borrowed Topsy whereas the kittens have been nonetheless nursing after which, tragically, Topsy had simply occurred to expire into visitors. The prosecuting legal professional declared prophetically that extra was behind this case than appeared. Nonetheless, the choose dominated Topsy’s loss of life an accident and “Mrs Tuttle walked majestically from the court, stepped into her luxurious limousine,” and swept off, in line with one reporter.

In addition to her condominium on Park Avenue, Tuttle owned a rustic dwelling in Larchmont. At some level, she moved her looking grounds to Westchester County and commenced concentrating on the purebred collies and shepherds that romped within the gardens of the wealthy. She grew to become increasingly brazen. And then she bought caught.

In June 1937, a mob of animal lovers swarmed the Eastchester courthouse, hoping to catch a glimpse of the notorious canine poisoner. Tuttle, then 65, swanned into court docket carrying her signature black costume, pearls, and white gloves. Her pinstriped lawyer escorted her to her seat. When it got here time to testify, Tuttle climbed up onto the stand and listed her bona fides—she had been a member of the Connecticut Humane Society, the Blue Cross Society in Larchmont, the New York Women’s League, and the New Rochelle Humane Society. She mentioned she’d been working to rescue canine and cats for greater than 35 years. Tuttle admitted that she had ordered her chauffeur to cease so she might method two canine in Larchmont, however she had solely needed to assist the collie as a result of it was caught in a fence. She definitely hadn’t fed the canine any poison.

The prosecuting legal professional identified that Tuttle had just lately purchased gelatin capsules at a drugstore that have been similar to these discovered on the scene of the crime. Tuttle admitted that she’d purchased the capsules, however solely as a result of she wanted to subdue animals in order that she might give them medical care. She had outfitted her limousine with canine biscuits and salmon, in addition to wire cat traps, onion luggage, and a bottle of chloroform.

The viewers within the courtroom broke out into astonished laughter at this level. Her testimony couldn’t have been extra incriminating. The temper within the room turned darker when a collection of eyewitnesses described her as a sadist. A girl named Mrs. Reisig, the top of the Larchmont Humane Society complaints division, mentioned that individuals had reported “cats, many of them valuable animals, disappearing all over Larchmont,” and that she’d realized that Mrs. Tuttle used to take cats to the police station to have them killed in a fuel tank there.

Two of Tuttle’s former chauffeurs informed the court docket that they’d stop as a result of they refused to collaborate in her cruelty. One driver mentioned he’d seen her poison a cat and abduct dozens of others to take them to the animal hospital and throw them immediately into the killing chamber. Another chauffeur described how Tuttle had wheedled a canine proprietor into handing over a collie after which snuffed it out.

The proof was damning sufficient that the choose levied the very best nice then allowable for animal cruelty—$500, the equal of about $10,000 right this moment. He might need locked her up, however she was thought of too previous to be price imprisoning.

So why on earth did she do it? Of course we’ll by no means know precisely what drove her, however I believe she might have craved reduction from the insufferable situation of being a no person. She was an growing old widow who’d as soon as been the chair of the Women’s League for Animals. But by the late Thirties, she was fading out of Manhattan society.

I think about her ordering her chauffeur to take her by means of essentially the most unique neighborhoods in Westchester, the place she might peer on the mansions with their excessive gates and guard homes. When she rolled down the automotive window, she might hear the pock of tennis balls and the squeals of kids in swimming swimming pools. Maybe it appealed to her, the concept that all she needed to do was drop a capsule in a yard and shortly the the individuals in these stunning homes could be shaking with terror and racked with tears.

Deborah Blum informed me that she’s generally amazed that so few individuals change into poisoners. She identified that all of us have easy accessibility to those homicide weapons—they’re in our garages and underneath our sinks. And but, intentional poisonings are uncommon. “It’s as if we have this universal pact not to poison each other,” she mentioned. “That is one of the few good check marks in our favor right now as a species.” The Juliet Tuttles of the world are an aberration.

I couldn’t discover a document of her loss of life, and so her ultimate years stay a thriller. But within the early Forties—after she was convicted and launched—newspapers have been issuing new warnings to pet homeowners in Westchester to maintain their canine and cats indoors as a result of a poisoner was on the free. “The poisoner is a sneaky and clever person,” the president of an area animal-rights group informed the press. “The only clue we have is that on one occasion in Bronxville an elderly woman in an automobile tried to coax animals up to her car and drove away hurriedly when detected.” The mysterious lady within the automotive reminded one reporter of Juliet Tuttle, the notorious Eastchester canine killer. She was, presumably, nonetheless at massive.

[ad_2]