[ad_1]

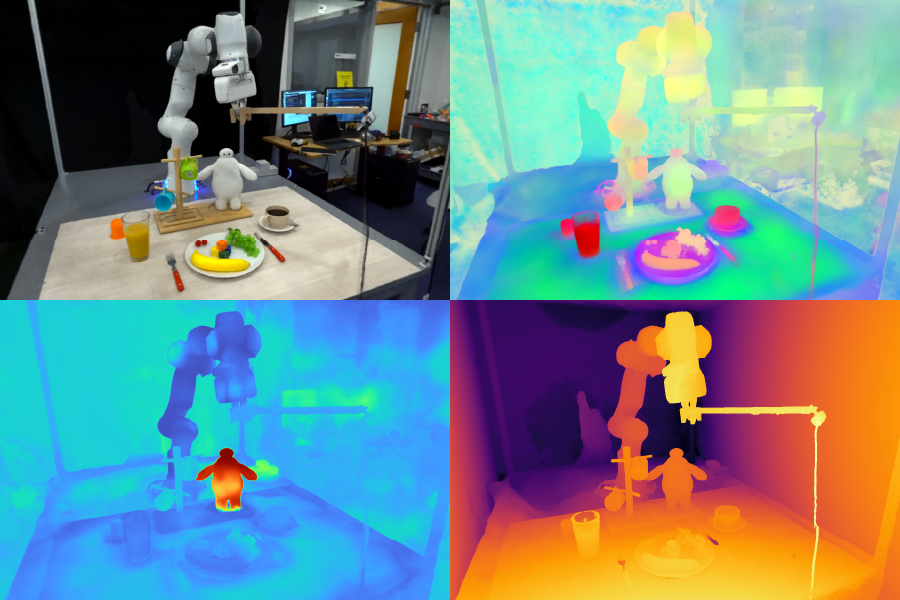

Feature Fields for Robotic Manipulation (F3RM) allows robots to interpret open-ended textual content prompts utilizing pure language, serving to the machines manipulate unfamiliar objects. The system’s 3D function fields could possibly be useful in environments that comprise hundreds of objects, resembling warehouses. Images courtesy of the researchers.

By Alex Shipps | MIT CSAIL

Imagine you’re visiting a good friend overseas, and also you look inside their fridge to see what would make for a terrific breakfast. Many of the gadgets initially seem overseas to you, with every one encased in unfamiliar packaging and containers. Despite these visible distinctions, you start to grasp what every one is used for and decide them up as wanted.

Inspired by people’ means to deal with unfamiliar objects, a bunch from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) designed Feature Fields for Robotic Manipulation (F3RM), a system that blends 2D photos with basis mannequin options into 3D scenes to assist robots establish and grasp close by gadgets. F3RM can interpret open-ended language prompts from people, making the strategy useful in real-world environments that comprise hundreds of objects, like warehouses and households.

F3RM provides robots the power to interpret open-ended textual content prompts utilizing pure language, serving to the machines manipulate objects. As a end result, the machines can perceive less-specific requests from people and nonetheless full the specified job. For instance, if a person asks the robotic to “pick up a tall mug,” the robotic can find and seize the merchandise that most closely fits that description.

“Making robots that can actually generalize in the real world is incredibly hard,” says Ge Yang, postdoc on the National Science Foundation AI Institute for Artificial Intelligence and Fundamental Interactions and MIT CSAIL. “We really want to figure out how to do that, so with this project, we try to push for an aggressive level of generalization, from just three or four objects to anything we find in MIT’s Stata Center. We wanted to learn how to make robots as flexible as ourselves, since we can grasp and place objects even though we’ve never seen them before.”

Learning “what’s where by looking”

The technique might help robots with selecting gadgets in giant achievement facilities with inevitable litter and unpredictability. In these warehouses, robots are sometimes given an outline of the stock that they’re required to establish. The robots should match the textual content supplied to an object, no matter variations in packaging, in order that clients’ orders are shipped appropriately.

For instance, the achievement facilities of main on-line retailers can comprise thousands and thousands of things, lots of which a robotic may have by no means encountered earlier than. To function at such a scale, robots want to grasp the geometry and semantics of various gadgets, with some being in tight areas. With F3RM’s superior spatial and semantic notion skills, a robotic might turn into simpler at finding an object, inserting it in a bin, after which sending it alongside for packaging. Ultimately, this is able to assist manufacturing unit staff ship clients’ orders extra effectively.

“One thing that often surprises people with F3RM is that the same system also works on a room and building scale, and can be used to build simulation environments for robot learning and large maps,” says Yang. “But before we scale up this work further, we want to first make this system work really fast. This way, we can use this type of representation for more dynamic robotic control tasks, hopefully in real-time, so that robots that handle more dynamic tasks can use it for perception.”

The MIT crew notes that F3RM’s means to grasp completely different scenes might make it helpful in city and family environments. For instance, the method might assist customized robots establish and decide up particular gadgets. The system aids robots in greedy their environment — each bodily and perceptively.

“Visual perception was defined by David Marr as the problem of knowing ‘what is where by looking,’” says senior creator Phillip Isola, MIT affiliate professor {of electrical} engineering and laptop science and CSAIL principal investigator. “Recent foundation models have gotten really good at knowing what they are looking at; they can recognize thousands of object categories and provide detailed text descriptions of images. At the same time, radiance fields have gotten really good at representing where stuff is in a scene. The combination of these two approaches can create a representation of what is where in 3D, and what our work shows is that this combination is especially useful for robotic tasks, which require manipulating objects in 3D.”

Creating a “digital twin”

F3RM begins to grasp its environment by taking footage on a selfie stick. The mounted digital camera snaps 50 photos at completely different poses, enabling it to construct a neural radiance area (NeRF), a deep studying technique that takes 2D photos to assemble a 3D scene. This collage of RGB images creates a “digital twin” of its environment within the type of a 360-degree illustration of what’s close by.

In addition to a extremely detailed neural radiance area, F3RM additionally builds a function area to reinforce geometry with semantic data. The system makes use of CLIP, a imaginative and prescient basis mannequin educated on a whole lot of thousands and thousands of photos to effectively be taught visible ideas. By reconstructing the 2D CLIP options for the photographs taken by the selfie stick, F3RM successfully lifts the 2D options right into a 3D illustration.

Keeping issues open-ended

After receiving a couple of demonstrations, the robotic applies what it is aware of about geometry and semantics to know objects it has by no means encountered earlier than. Once a person submits a textual content question, the robotic searches by the house of potential grasps to establish these most certainly to achieve selecting up the article requested by the person. Each potential possibility is scored primarily based on its relevance to the immediate, similarity to the demonstrations the robotic has been educated on, and if it causes any collisions. The highest-scored grasp is then chosen and executed.

To reveal the system’s means to interpret open-ended requests from people, the researchers prompted the robotic to choose up Baymax, a personality from Disney’s “Big Hero 6.” While F3RM had by no means been immediately educated to choose up a toy of the cartoon superhero, the robotic used its spatial consciousness and vision-language options from the inspiration fashions to resolve which object to know and easy methods to decide it up.

F3RM additionally allows customers to specify which object they need the robotic to deal with at completely different ranges of linguistic element. For instance, if there’s a steel mug and a glass mug, the person can ask the robotic for the “glass mug.” If the bot sees two glass mugs and one among them is crammed with espresso and the opposite with juice, the person can ask for the “glass mug with coffee.” The basis mannequin options embedded throughout the function area allow this degree of open-ended understanding.

“If I showed a person how to pick up a mug by the lip, they could easily transfer that knowledge to pick up objects with similar geometries such as bowls, measuring beakers, or even rolls of tape. For robots, achieving this level of adaptability has been quite challenging,” says MIT PhD pupil, CSAIL affiliate, and co-lead creator William Shen. “F3RM combines geometric understanding with semantics from foundation models trained on internet-scale data to enable this level of aggressive generalization from just a small number of demonstrations.”

Shen and Yang wrote the paper below the supervision of Isola, with MIT professor and CSAIL principal investigator Leslie Pack Kaelbling and undergraduate college students Alan Yu and Jansen Wong as co-authors. The crew was supported, partially, by Amazon.com Services, the National Science Foundation, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Office of Naval Research’s Multidisciplinary University Initiative, the Army Research Office, the MIT-IBM Watson Lab, and the MIT Quest for Intelligence. Their work can be introduced on the 2023 Conference on Robot Learning.

MIT News