[ad_1]

During the Great Recession, public discourse in regards to the economic system underwent one thing of a Great Disappointment.

For a lot of the nation’s historical past, most Americans assumed that the longer term would deliver them or their descendants larger affluence. Despite periodic financial crises, the general story gave the impression to be considered one of progress for each stratum of the inhabitants. Those expectations had been largely borne out: The way of life loved by working-class Americans for a lot of the mid-Twentieth century, for instance, was far superior to that loved by prosperous Americans a era or two earlier.

But after the 2008 monetary disaster, these assumptions had been upended by a interval of intense financial struggling coupled with a newfound curiosity amongst economists within the subject of inequality. Predictions of financial decline took over the dialog. America, a rustic lengthy identified for its inveterate optimism, got here to dread the longer term—through which it now appeared that most individuals would have much less and fewer.

Three arguments supplied the mental basis for the Great Disappointment. The first, influentially superior by the MIT economist David Autor, was that the wages of most Americans had been stagnating for the primary time in dwelling reminiscence. Although the earnings of common Americans had roughly doubled as soon as each era for a lot of the earlier century, wage development for a lot of the inhabitants started to flatline within the Eighties. By 2010, it regarded as if poorer Americans confronted a future through which they might not count on any actual enchancment of their way of life.

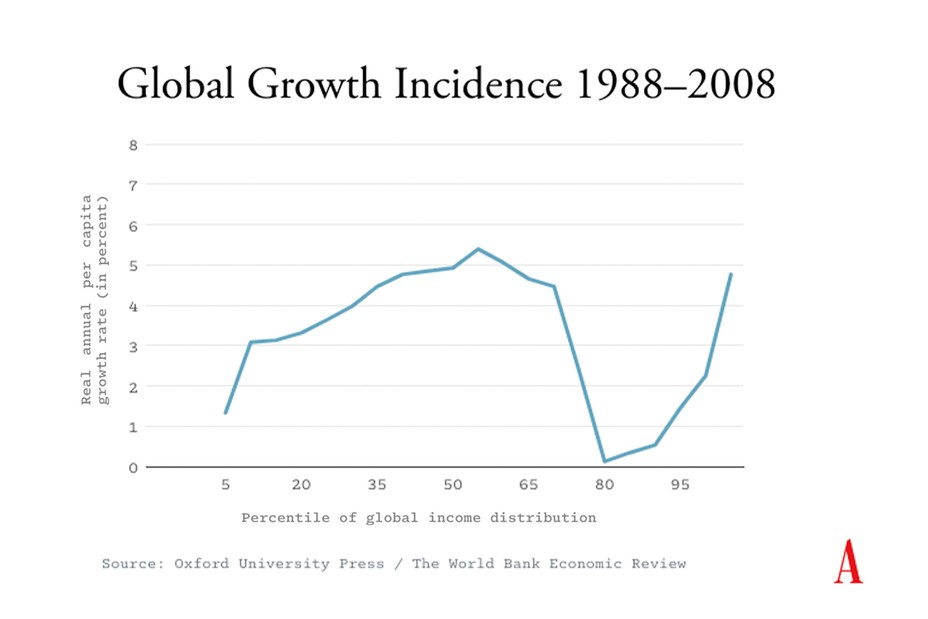

The second argument needed to do with globalization’s affect on the worldwide distribution of earnings. In a graph that got here to be often known as the “elephant curve,” the Serbian American economist Branko Milanović argued that the world’s poorest folks had been experiencing solely minor earnings development; that the center percentiles had been benefiting mightily from globalization; that these within the upper-middle section—which included many industrial employees and other people within the service business in wealthy international locations, together with America—had seen their incomes stagnate; and that the very richest had been making out like bandits. Globalization, it appeared, was a blended blessing, and a distinctly regarding one for the underside half of wage earners in industrialized economies such because the United States.

The remaining, and most sweeping, argument was in regards to the nature and causes of inequality. Even as a lot of the inhabitants was simply holding its personal in prosperity, the wealth and earnings of the richest Americans had been rising quickly. In his 2013 shock greatest vendor, Capital within the Twenty-First Century, the French economist Thomas Piketty proposed that this pattern was more likely to proceed. Arguing that the returns on capital had lengthy outstripped these of labor, Piketty appeared to recommend that solely a calamitous occasion akin to a serious battle—or a radical political transformation, which didn’t seem like on the horizon—might assist tame the pattern towards ever-greater inequality.

The Great Disappointment continues to form the best way many Americans take into consideration the present and future state of the economic system. But because the pandemic and the rise of inflation have altered the world economic system, the mental foundation for the thesis has begun to wobble. The causes for financial pessimism have began to look much less convincing than they as soon as had been. Is it time to revise the core tenets of the Great Disappointment?

One of the most distinguished labor economists within the U.S., Autor has over the previous decade supplied a lot of the proof concerning the stagnation of American employees’ incomes, particularly for these with no faculty diploma.

The U.S. economic system, Autor wrote in a extremely influential paper in 2010, is bifurcating. Even as demand for high-skilled employees rose, demand for “middle-wage, middle-skill white-collar and blue-collar jobs” was contracting. America’s economic system, which had as soon as supplied loads of middle-class jobs, was splitting right into a extremely prosperous skilled stratum and a big the rest that was changing into extra immiserated. The general end result, in accordance with Autor, was “falling real earnings for noncollege workers” and “a sharp rise in the inequality of wages.”

Autor’s previous work on the falling wages of a serious section of the American workforce makes it all of the extra notable that he now sounds much more optimistic. Because corporations had been desperately trying to find employees on the tail-end of the pandemic, Autor argues in a working paper printed earlier this yr, low-wage employees discovered themselves in a a lot better bargaining place. There has been a exceptional reversal in financial fortunes.

“Disproportionate wage growth at the bottom of the distribution reduced the college wage premium and reversed the rise in aggregate wage inequality since 1980 by approximately one quarter,” Autor writes. The massive winners of current financial traits are exactly these teams that had been unnoticed in previous a long time: “The rise in wages was particularly strong among workers under 40 years of age and without a college degree.”

Even after accounting for inflation, Autor reveals, the underside quarter of American employees has seen a major enhance in earnings for the primary time in years. The scholar who beforehand wrote in regards to the “polarization” within the U.S. workforce now concludes that the American economic system is experiencing an “unexpected compression.” In different phrases, the wealth hole is narrowing with stunning velocity.

Autor just isn’t the one main economist who is asking into doubt the underpinnings of the Great Disappointment. According to Milanović, his “elephant curve” proved so influential partially as a result of it confirmed fears many individuals had in regards to the results of globalization. His well-known graph was, he now admits, an “empirical confirmation of what many thought.” He is not so positive about that piece of typical knowledge.

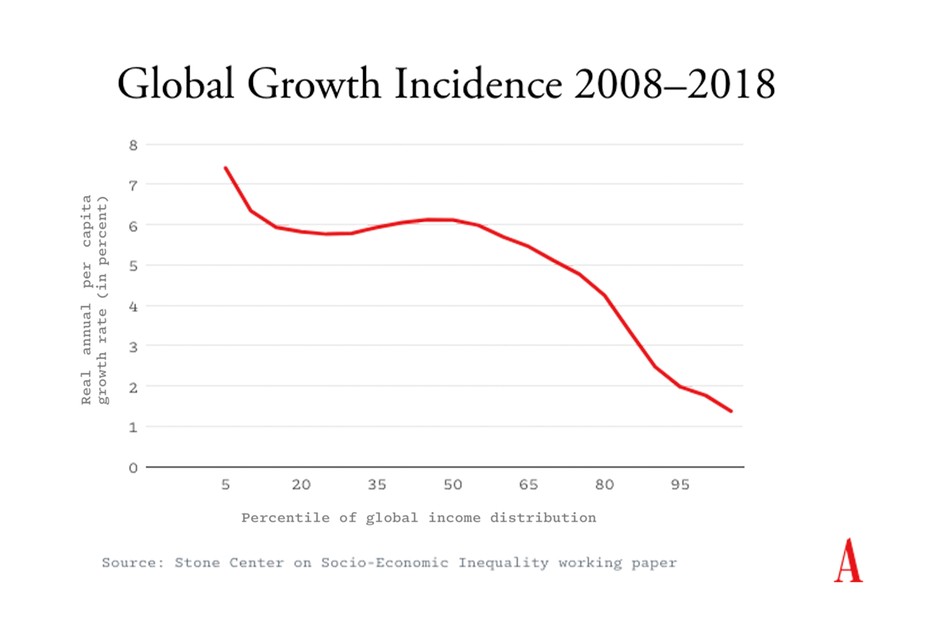

A couple of years in the past, Milanović got down to replace the unique elephant curve, which was primarily based on information from 1988 to 2008. The consequence got here as a shock—a constructive one. Once Milanović included information for an additional decade, to 2018, the curve modified form. Instead of the attribute “rise, fall, rise again” that had given the curve its viral title, its steadily falling gradient now appeared to color an easy and way more optimistic image. Over the 4 a long time he now surveyed, the incomes of the poorest folks on the earth rose very quick, these of individuals towards the center of the distribution pretty quick, and people of the richest reasonably sluggishly. Global financial circumstances had been enhancing for practically everybody, and, opposite to traditional knowledge, it was essentially the most needy, not essentially the most prosperous, who had been reaping the best rewards.

In a current article for Foreign Affairs, Milanović goes even additional. “We’re frequently told,” he writes, that “we live in an age of inequality.” But once you take a look at the newest international information, that seems to be false: In reality, “the world is growing more equal than it has been for over 100 years.”

To at the present time, Piketty stays the patron saint of the Great Disappointment. No thinker is invoked extra usually to justify the speculation. But even Piketty’s pessimistic analysis, made a decade in the past, has come to look a lot much less dire.

In half, it is because Piketty’s work has are available for criticism from different economists. According to at least one influential line of argument, Piketty mistook why returns on capital had been increased than returns to labor in lots of industrialized international locations within the a long time after World War II. Absent concerted stress to stop this, Piketty had argued, the character of capitalism would at all times favor billionaires and big companies over extraordinary employees. But in accordance with Matthew Rognlie, an economist at Northwestern University, Piketty’s rationalization for why inequality elevated throughout that interval was primarily based on a misinterpretation of the info.

The outsize returns on capital through the latter half of the Twentieth century, Rognlie argues, had been primarily as a result of large development in home costs in metropolitan facilities akin to Paris and New York. If returns on capital had been bigger than returns to labor over this era, the rationale was not a normal financial pattern however particular political components, akin to restrictive constructing codes. In addition, the principle beneficiaries weren’t the billionaires and massive companies on which Piketty targeted; reasonably, they had been the sorts of upper-middle-class professionals who personal the majority of housing inventory in main cities.

Economists proceed to debate whether or not such criticisms hit the mark. But at the same time as Piketty defended his work, he himself began to strike a extra optimistic word in regards to the long-term construction of the economic system. In his 2022 guide, A Brief History of Equality, he talks in regards to the rise of inequality as an anomaly. “At least since the end of the eighteenth century there has been a historical movement towards equality,” he writes. “The world of the 2020s, no matter how unjust it may seem, is more egalitarian than that of 1950 or that of 1900, which were themselves in many respects more egalitarian than those of 1850 or 1780.”

Like Autor and Milanović, Piketty appears to have concluded that the thesis of the Great Disappointment was, in key respects, flawed.

It could be untimely to place worries about stagnating incomes or rising inequality to relaxation. The three former prophets of doom all emphasize the position that social and political components play in shaping financial outcomes. As a consequence, they see current wage development for poorer Americans as prompted partially by the expansionary financial insurance policies that each Donald Trump and Joe Biden pursued in response to the pandemic.

Similarly, the massive positive aspects that a number of the poorest folks on the earth have made in current a long time derive partially from their governments’ efforts to make use of industrial coverage to form the affect of globalization on their international locations. Whether, as Piketty has argued, the returns on capital will in the long term outstrip the returns to labor depends upon political choices about taxation and redistribution, in regards to the energy of commerce unions and the foundations governing labor markets.

Recent excellent news about our financial prospects mustn’t lead us to conclusions that might shortly become overexuberant. But we must also keep away from perpetuating an instinctive pessimism that appears much less and fewer warranted. Although pessimism could appear good or shrewd, cynicism about our collective capacity to construct a greater world solely makes it tougher to win assist for the type of financial insurance policies we have to create that future.

Progressives generally appear to consider that they will mobilize folks by making the longer term look scary. But when voters really feel threatened, it’s often unscrupulous reactionaries who make unrealistic guarantees and scapegoat outsiders who profit. Wage stagnation and rising inequality are nonetheless actual risks about which we should stay vigilant—however the truth that a greater financial future has come to look a great deal extra achievable needs to be trigger for full-throated celebration.

[ad_2]