[ad_1]

A

t the small elementary faculty in Jouy-sous-les-Côtes, in northeastern France, Gisèle Marc knew the rumor about her: that her mother and father weren’t her actual mother and father, and her actual mom will need to have been a whore. It was the late Nineteen Forties, simply after the battle, a time when whispered tales like this one handed from mother and father to youngsters. Women who had been mentioned to have slept with occupying troopers—“horizontal collaborators”—had their heads shaved and had been publicly shamed by offended crowds. In the schoolyard, youngsters jeered at those that had been mentioned to be born of “unknown fathers.”

The concept that Gisèle may need been deserted by somebody of in poor health reputation made her terribly ashamed. At the age of 10, she gathered her braveness and confronted her mom, who instructed her the reality: We adopted you once you had been 4 years previous; you spoke German, however now you’re French. Gisèle and her mom hardly talked about it once more.

Gisèle discovered her adoption file, hidden in a drawer in her mother and father’ room, and once in a while she snuck a take a look at it. It contained little data. When she was 18, she burned it on the range. “I said to myself, If I want to live, I have to get rid of all this,” she instructed me.

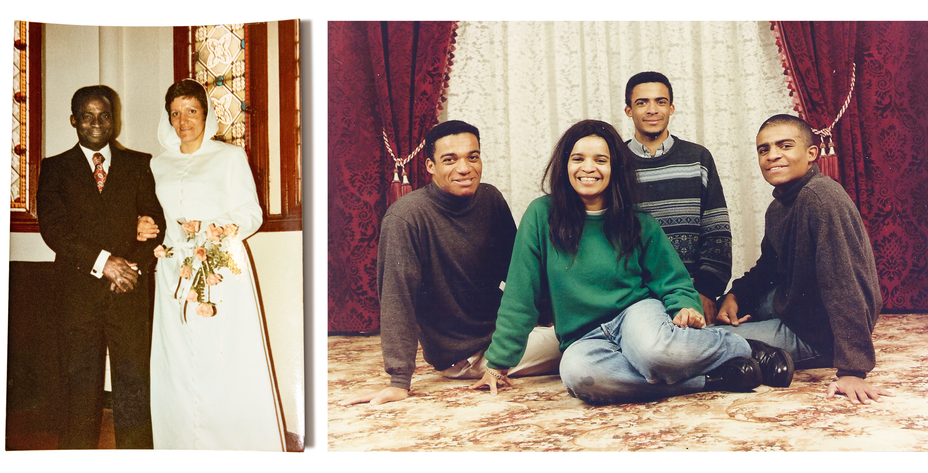

Gisèle is 79 now, and she or he doesn’t remorse burning the papers. For a time, she was capable of put apart questions on her origins. At 17, she took a job in a youngsters’s house and hospital and realized she had discovered her calling. She spent her profession working primarily in day-care facilities, and ultimately based her personal. In 1972, she married Justin Niango, a chemistry pupil from the Ivory Coast. They purchased an previous resort simply behind Stanislas Square in Nancy and turned it right into a home.

I visited Gisèle there in June. It was straightforward to think about the colourful household life that when happened inside: her youngsters—Virginie, Gabriel, Grégoire, and Matthieu—operating up and down the steps and enjoying devices of their rooms. At faculty, they had been typically the one Black children of their class. Gisèle has a variety of tales concerning the merciless feedback made via the years; all of the tales finish along with her confronting the offender.

Gisèle held off on telling her youngsters that she had been adopted, as a result of she was fearful that the revelation may weaken their bonds along with her mother and father. Sometimes, although, the key “burned a bit.” She knew she would share it will definitely.

When her mom died, in 2004, she gathered her youngsters and instructed them. They had been shocked, and requested questions whose solutions she didn’t know.

After years of denial, Gisèle longed to search out these solutions. She remembered the title and hometown that had been listed in her burned adoption file: Gisela Magula, born in Bar-le-Duc, in northeastern France. She began her analysis there, and went on to write down to the Arolsen Archives, the worldwide middle on Nazi persecution, in Germany, to ask if there was any point out of her within the group’s intensive information.

In March 2005, Gisèle acquired a reply: She had not been born in Bar-le-Duc in spite of everything, however close to Liège, Belgium, in a Nazi maternity house on the Château de Wégimont. That house and others prefer it had been arrange by the SS, an elite corps of Nazi troopers, below the umbrella of the Lebensborn affiliation, via which the regime sought to encourage the delivery of infants of “good blood” with a view to hasten its final purpose of Aryan racial purity.

Everything Gisèle believed about herself wavered. The household she’d spent her grownup life defending in opposition to racism, she realized, descended from one in all historical past’s darkest racial tasks.

N

azism was an ideology of destruction, one which held as its main goal the elimination of “inferior races.” But one other, equally fervent facet of the Nazi credo was targeted on an imagined type of restoration: As quickly as they got here to energy, the Nazis got down to produce a brand new technology of pure-blooded Germans. The Lebensborn affiliation was a key a part of this plan. Established in 1935 below the auspices of the SS, it was meant to encourage procreation amongst members of the Aryan race by offering birthing moms with consolation, monetary assist, and, when mandatory, secrecy. The affiliation’s headquarters had been in Munich, within the former villa of the author Thomas Mann, who had left Germany in 1933. In 1936, it opened its first maternity house, in close by Steinhöring.

The SS was overseen by Heinrich Himmler, who hoped that its elite troopers would function a racial vanguard for a revitalized Germanity. “As far as the value of our blood and the numbers of our population are concerned, we are dying out,” he mentioned in a 1931 handle to the SS. “We are called upon to establish foundations so that the next generation can make history.” An agronomist by coaching, Himmler supervised this endeavor with a stage of consideration that bordered on voyeurism; initially, all SS leaders’ marriage purposes needed to be referred to him. All had been anticipated to breed: Four youngsters was thought-about “the minimum amount … for a good sound marriage.” Himmler had no drawback with childbearing exterior marriage, and criticized the Catholic Church’s hostility towards illegitimate births. Raising “illegitimate or orphaned children of good blood” must be an “accepted custom,” Himmler wrote. In 1939, he issued an order that known as on members of the SS to procreate wherever they may, together with with girls to whom they weren’t married.

According to Himmler, the Lebensborn houses had been meant “primarily for the brides and wives of our young SS men, and secondarily for illegitimate mothers of good blood.” But the latter had been, in observe, a majority. Far from the eyes of the world, single moms might give delivery in Lebensborn houses and, in the event that they wished to, abandon their infants, who would obtain one of the best care earlier than being positioned in an adoptive household—as long as the organic mother and father met the racial standards (pictures of each had been required). Early candidates needed to meet a top requirement, and needed to show their racial and medical health going again two generations. The German historian Georg Lilienthal discovered that originally, lower than half of the ladies who utilized had been accepted.

Lebensborn staff took word of how the moms behaved throughout childbirth, and required them to breastfeed their youngsters if they may. “The woman has her own battlefield,” Adolf Hitler mentioned in 1935. “With every child she brings into the world, she fights her battle for the nation.”

The girls additionally acquired a each day “ideological education,” based on the historian Lisa Pine. Some of the infants got a non-Christian first title by Lebensborn workers in a ceremony impressed by previous Nordic customs. Under a Nazi flag and a portrait of the fürher, in entrance of a congregation, the grasp of ceremonies would maintain an SS dagger over the new child and recite this creed: “We take you into our community as a limb of our body. You shall grow up in our protection and bring honor to your name, pride to your brotherhood, and inextinguishable glory to your race.” Through this ceremony, they believed, the kid turned a member of the SS clan, ceaselessly linked to the Reich.

By October 11, 1943, when Gisèle was born, there have been about 16 Lebensborn services all through Nazi-occupied Europe. She arrived 4 days too late to have Himmler as her godfather; the Reichsführer personally sponsored the youngsters who shared his birthday, October 7.

One afternoon final spring, I sat with Gisèle in her lounge, dozens of paperwork and images unfold out earlier than us. A brief lady whose white hair is shot via with a streak of brown, Gisèle is without delay reserved and simple, with a wry humorousness. “Himmler really bungled with me,” she joked, referencing her marriage to an African man and their mixed-race household.

Gisèle rejects the concept there’s a connection between her profession and her early years spent in a really completely different form of day care—she selected her path, in spite of everything, lengthy earlier than she knew the place she had actually come from.

Still, she doesn’t decrease the truth that her life story is inextricable from the historical past of Nazism. She has typically questioned how her origins may form what she calls her “internal memory”: She has all the time been terribly afraid of army vans, trains, and leather-based boots. She can not bear to listen to infants crying; at her day care, she would typically depart her workplace to consolation the little ones. She worries, too, that she someway handed one thing evil on to her youngsters via her genes.

An opportunity encounter helped Gisèle hint her origins. Just a few months after her mom’s demise, simply as she started her analysis, her cousin went to a funeral the place a tall man with blond hair gave a eulogy for the departed, a trainer who had believed in him. The man, Walter Beausert, talked about his arrival in France as a toddler, in a convoy from Germany. Gisèle’s cousin, who was sufficiently old to recollect Gisèle’s adoption and knew that she’d come from Germany, struck up a dialog with Beausert after the funeral. Her cousin questioned whether or not Gisèle may need been in the identical convoy.

Beausert was a Lebensborn baby. A decade earlier, he had been the primary individual in France to testify concerning the Lebensborn, in a 1994 tv report on his quest all through Europe to search out the place he was born. Gisèle’s cousin put her in contact with Beausert, who quickly helped Gisèle recuperate her personal historical past.

The story that Gisèle has pieced collectively remains to be stuffed with holes, however she now is aware of the id of her organic mom. Marguerite Magula was a Hungarian lady who immigrated to Brussels along with her mother and father and sister in 1926. Marguerite ultimately went to Germany to work, along with her mom and sister, in a garment manufacturing facility in Saarbrücken. When she bought pregnant, in 1943, she ran away and returned to Brussels. Dorothee Schmitz-Köster, the creator of Lifelong Lebensborn: The Desired Children of the SS and What Became of Them, instructed me that by then, the Lebensborn program had considerably loosened its standards: A fervent perception in National Socialism might make up for being brief, as Marguerite was, although an Aryan certificates, a well being certificates, and a certificates of hereditary well being had been nonetheless necessary for each mother and father.

Gisèle’s emotions towards Marguerite have modified over time. When she realized from the Steinhöring archives that some moms had searched for his or her youngsters after the battle, making an attempt to get them again, Gisèle got here to hate her. “She never sought me out,” Gisèle mentioned. “I have no compassion, nothing; quite the opposite. That’s not a mother.” A postwar doc denying Marguerite’s request for Hungarian citizenship (she and her sister had been then stateless) mentions her “bad life.” Had Gisèle and Marguerite met, perhaps she might have defined. But Marguerite died in 2001, only a few years earlier than Gisèle started her search.

Gisèle has been much less curious concerning the id of her father; she imagines him because the stereotype of an SS officer—undoubtedly “a bastard.”

In 2009, Gisèle met a half brother, Claude, born after the battle, who was raised by Marguerite. They nonetheless go to one another once in a while. Claude, she mentioned, describes their mom as having mistreated him. He as soon as instructed Gisèle she was fortunate to not have grown up with their mom.

L

ike Gisèle, Walter Beausert owed the invention of his origins to likelihood. At the delivery of his first daughter, Valérie, in 1966, the midwife stared at Beausert, then 22 years previous. Behind his helmet of straight blond hair, she observed his light-blue eyes—one in all them was a glass eye that by no means closed—and remembered the 17 babies who had arrived by practice on the hospital in Commercy in 1946. “I think you come from Germany,” she mentioned to him. It confirmed one thing Walter had all the time suspected.

Walter was the one baby in that convoy to France by no means to have been adopted. He grew up in youngsters’s houses and have become a guarded, powerful teenager. Unusually for a Lebensborn baby, Beausert was circumcised. He by no means knew why. “My father was obsessed with the search for his family. He looked for his mother all his life,” Walter’s daughter Valérie, now 56, instructed me once we met at an previous art-nouveau brasserie in Nancy.

In 1994, whereas filming the tv report concerning the Lebensborn, Walter traveled to the location of the previous Lebensborn house on the Château de Wégimont, the place he heard from locals a few lady named Rita, a Lebensborn cook dinner, who had had a child boy named Walter. As German troopers tried to take Walter away from Rita, the story went, he was dropped and his left eye was injured. This was the lead the grown-up Walter had been ready for—Rita, he got here to consider, was his mom.

“Except that’s not true,” Valérie mentioned. “We met this Rita; we know who this Walter is. He’s not my father. But he didn’t want to hear anything about it. He said Rita had a second child who was also named Walter. I told him, ‘This doesn’t make any sense.’ His denial was pathological.”

Valérie, who has the identical light-blue eyes and straight blond hair as her father, was known as a “sale boche”—“dirty Kraut”—at college throughout her childhood, simply as her father had been known as a “white rat.” In 1986, Valérie fell in love with a person who was a refugee from Vietnam. “My son’s father was the first person of color in our village,” she mentioned. “But for me it was a nonissue. I felt like an outsider myself.”

Their son, Lâm, was born with one brown eye and one blue eye. One eye—the blue one—offered with a deficiency. The physician recognized a congenital abnormality that might trigger blindness, which Valérie additionally carried and had handed on to him. Her father’s glass eye, she realized, was not the results of an damage in any respect. “When my son had to undergo an operation, I told my father, ‘You see, it is congenital.’” Her father was outraged, Valérie recalled: “Nonsense! You can’t say that!”

It wasn’t simply that Walter wished to consider that his glass eye was the results of his organic mom’s wrestle to guard him from German troopers; he was additionally afraid of illness, of being “a carrier of defects,” Valérie mentioned, and went to nice lengths to show his superior power and stoicism. One day, whereas he was chopping wooden, his pal’s chainsaw ripped via a trunk, reducing each of Walter’s calves to the bone. Walter made himself two tourniquets and drove house. Valérie remembers him strolling up the steps as if nothing had occurred, each legs bloody, and calmly asking her to name an ambulance.

Walter discovered others’ fragility insufferable. When his spouse, Valérie’s mom, was recognized with most cancers, Valérie typically stored him out of her room. “He would tell her, ‘You have to fight; you must eat; that’s how you get better.’ It was a form of psychological abuse.”

To Valérie, this trait in her father was a troubling echo of the Nazi emphasis on bodily superiority. “A young German must be as swift as a greyhound, as tough as leather, and as hard as Krupp steel,” Hitler proclaimed in 1935. Lebensborn youngsters born with circumstances akin to Down syndrome, cleft lip, or clubfoot had been thrown out of the houses, or killed.

Sometimes Valérie worries about what she, and her son, may need inherited from her father. “When I see some of my son’s character traits—a little tough, a little authoritarian—which could belong to my father but also to me, I always have this fleeting anxiety: Did we pass along something of the Lebensborn?”

I

n the summer season of 1945, Life journal printed a report, with footage by the photographer Robert Capa, on the “super babies” of a Lebensborn house. “The Hohenhorst bastards of Himmler’s men are blue-eyed, flaxen-haired and pig fat,” one caption learn. “Too much porridge, plenty of sunlight have made this Nazi baby in hand-knitted suit and bootees so fat and healthy that he completely fills his over-sized carriage,” learn one other. “Grown pig fat under care and overstuffing Nazi nurses, they now pose to the Allies a problem yet to be solved.” The tone provides an thought of the extent of resentment that Americans and Europeans felt in 1945 towards those that had been spared the battle’s horrors—even toddlers.

But not all Lebensborn infants had been blue-eyed, flaxen haired, and even, for that matter, “pig fat.” Likely due to the shortage of bonding with a single caregiver, some youngsters had been developmentally delayed. Medical exams carried out after the battle point out that Walter was underweight. A doc from French social staff describes Gisèle as having had tantrums upon her arrival in France.

For Gisèle and her fellow Lebensborn youngsters, the Allies’ liberation of Belgium marked the start of a journey—in wicker cradles wedged at the back of army vans—via a devastated Europe. In The Factory of Perfect Children, the French journalist Boris Thiolay recounts that German troopers in retreat left the Lebensborn house close to Liège on September 1, 1944, with about 20 toddlers. After a number of stops in Germany and Poland, the youngsters discovered themselves on the very first Lebensborn, in Steinhöring. Walter Beausert had ended up there too.

In Steinhöring, SS officers had been crammed along with youngsters and pregnant girls from different establishments that had been now closed. Boxes of paperwork cluttered the corridors of the maternity ward, the place girls continued to present delivery.

When the information of Hitler’s demise broke, officers burned as many paperwork as they may. Thiolay describes the objectives of this purge: “The birth registers, the identity of the children, the fathers, the organization chart, the names of the people in charge: everything must disappear. The evidence of the Lebensborn’s very existence must be removed.” But the Nazis’ obsession with paperwork made absolutely expunging the information an not possible job—there have been too many.

Just a few days after Hitler’s demise, a small detachment of U.S. troopers arrived in Steinhöring, and the youngsters modified fingers: The Americans had been accountable for them now.

Later in 1945, Gisèle and Walter had been transferred to Kloster Indersdorf, 9 miles from Dachau, the place they had been housed in a Twelfth-century monastery that had been requisitioned by the U.S. Army for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) to make use of as a reception middle for displaced youngsters. There, the Lebensborn youngsters lived along with survivors: Jewish youngsters who had made it out of the focus camps, in addition to Eastern and Central European gentile youngsters who had been pressured laborers in the course of the battle.

The older youngsters had been inspired to assist the youthful ones. An image exhibits three small blond women gently combing infants’ hair and spoon-feeding them as in the event that they had been enjoying with dolls. Another picture exhibits a gaggle of infants on a checkered comforter below the watch of the American social employee Lillian Robbins and a Sister of Mercy. In the nook, sitting on the ground away from the opposite toddlers, is little Walter, one eye closed, smiling on the photographer.

The UNRRA workers tried to search out the youngsters’s surviving relations, if there have been any, although some youngsters had no recorded id. Some got an approximate delivery date. This was maybe what occurred with Walter Beausert, whose official date of delivery falls on a suspicious, although in fact doable, date: January 1, 1944. His birthplace was unknown, however, possible as a result of he was believed to have beforehand lived at a Lebensborn house in France, UNRRA workers determined to ship him there from Indersdorf.

As for younger Gisela, her file confirmed that she was born in “Wégimont” (omitting the château’s full title), which workers believed to be a French city. She joined Walter within the convoy sure for the Meuse area of France, whose inhabitants had by no means recovered from World War I. Gisela turned Gisèle, and her life as a French baby started.

W

ere they “survivors,” these toddlers who owed their existence to Nazi delivery coverage, who ate recent fruit and porridge whereas different infants had been gassed or starved to demise?

On October 10, 1947, in Nuremberg, 4 Lebensborn leaders appeared earlier than a particular American army tribunal as a part of the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials, which prosecuted ancillary Nazi leaders. Three fees had been introduced in opposition to them: crimes in opposition to humanity, battle crimes, and membership in a legal group. Three out of the 4 leaders had been discovered responsible of the third cost. But the tribunal established that the Lebensborn had been solely a “welfare institution.” The youngsters, subsequently, weren’t thought-about victims.

Until the Nineteen Seventies, Lebensborn houses had been handled as a rumor, or described as stud farms the place SS males mated with racially chosen girls. The first guide to be printed about Lebensborn got here out in France in 1975 and contributed to this misunderstanding by suggesting that the “nurses” had been actually chosen to be breeding moms. Georg Lilienthal wrote the primary educational work on this system, in 1986.

In the 9 years this system lasted, not less than 9,200 youngsters had been born within the houses. Some 1,200 had been born in Norway, which had probably the most SS maternity houses exterior Germany. After the battle, these youngsters, together with girls who had been suspected of getting had affairs with German troopers, had been ostracized. Some of those girls had been even interned in camps. France had just one Lebensborn house, which operated for lower than a yr, so Lebensborn youngsters there have been far much less more likely to be acknowledged as such.

In 2011, Gisèle and Walter traveled to Indersdorf to affix the annual commemoration held there by former residents of UNRRA’s reception middle; Gisèle described the organizers as “Jewish children,” simply as she nonetheless refers to herself as a “child of the Lebensborn.” “It was extraordinary” to be included within the ceremony, she instructed me. While she was in Indersdorf, she went to go to Dachau twice. She felt she wanted to confront what she may need believed in had she been raised in an SS household.

Together, Gisèle and Walter began the Association for the Memory of Child Victims of the Lebensborn in 2016, an effort to encourage public recognition of Lebensborn youngsters as victims of battle.

Walter, for his half, turned obsessive about gaining acceptance from the Jewish neighborhood. He studied the Torah and recognized as a Zionist. “He used to celebrate Jewish holidays,” Valérie remembers. “His Jewish friends were a great help to my father. To tell him, ‘You are also a victim, Walter’ was the greatest gift.”

He died in 2021, sporting a Star of David round his neck. He had been sick, and dwelling in a retirement house. Just a few days earlier, for the primary time in his life, he had admitted that perhaps Rita was not his mom.

Valérie has stored a comb that also comprises her father’s hair. One day, she hopes to search out out what secrets and techniques his DNA may include.

G

isèle’s husband, Justin, died 15 years in the past, however she nonetheless spends almost each winter in Africa, in his village, the place she is “famous,” she mentioned, partly as a result of residents noticed her on TV, in a phase concerning the Lebensborn.

At house in Nancy, she retains {a photograph} of her organic mom on show, although she doesn’t take a look at it a lot anymore. “It’s my heritage. I don’t want to forget that I was born from this woman,” she instructed me. All she desires now could be for her story to be instructed. “I’m modest,” she joked. “I want the whole world to know about it.”

Her son Gabriel married a German lady, and her grandchildren converse German, a language she has utterly forgotten. “It shows that history goes on,” she mentioned. Her son Matthieu is engaged on a guide concerning the Lebensborn, and along with his spouse, Camille, he wrote a play concerning the youngsters’s story. Recently, I attended a studying at a small theater in Paris. I watched Gisèle, seated subsequent to her daughter Virginie, as she watched her personal story acted out.

“They say history is written by the victors,” one actor mentioned. “But most of all, it’s written by the adults.” Gisèle discreetly dried her tears behind her glasses.