[ad_1]

Osamu Dazai’s 75-year-old novel of alienation

This is an version of the revamped Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly information to the perfect in books. Sign up for it right here.

The lonely, alienated younger male narrator is a standard determine in literature throughout time and place. Readers encounter him within the unnamed, frenzied protagonist who stalks round Christiania in Knut Hamsun’s Hunger; in Leopold Bloom as he wanders James Joyce’s Dublin in Ulysses; and in J. D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, who ditches his boarding college for New York City. In Osamu Dazai’s 1948 cult-classic novel, No Longer Human, which turns 75 this 12 months, the protagonist Yozo Oba may deliver a few of these characters to thoughts as he whiles away his days in Nineteen Thirties Tokyo. Like a few of these different narrators, he’s adrift on this planet, espousing a “pessimistic view of social humanity,” my colleague Jane Yong Kim wrote this week.

First, listed here are three new tales from The Atlantic’s Books part:

Yozo struggles with conventions, dismisses the individuals who present him kindness, and relentlessly criticizes himself. The occasions in his life mimic main moments in Dazai’s personal, and the creator’s loss of life by suicide shortly earlier than No Longer Human’s publication has contributed to its fantasy. But finally, it’s the e book’s conversational tone—the singularity of that self-deprecating voice—that has made its repute, and stored it related in the present day.

In truth, the stress between what the lonely narrator says he needs and what he really wishes feels deeply modern. Reacting to the world with bemusement and criticism requires solely wit and statement; admitting a real want calls for vulnerability—you won’t get what you’ve requested for. Yozo can’t deliver himself to say that he wants different individuals, regardless that he clearly depends on mates to look after him or assist him get by in Tokyo. In that manner, Kim writes, Dazai’s works operate not simply as tales of estrangement, however as “modern portraits of human connection.”

The Cult Classic That Captures the Stress of Social Alienation

What to Read

I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself, by Marisa Crane

In Crane’s imaginative debut, prisons have been abolished, however punishment hasn’t, nor has surveillance. The authoritarian authorities offers individuals convicted of crimes a second, literal shadow, and extra in the event that they reoffend. These residents have restricted rights and assets, and endure quite a lot of social stigma. When the narrator Kris’s spouse dies giving start to their youngster, the child is penalized for inadvertently killing her mom. Kris, now each a widow and a brand new mother, has a second shadow too, so she and her daughter each turn into pariahs … Her bond along with her youngster grows: They study to embrace their shadows as a part of their lives, giving them names and enjoying with them … Kris slowly emerges from her morass of sorrow and builds connections with new mates and neighbors, intent on giving her daughter hope, gumption, and a group of people that gained’t fail her. — Ilana Masad

From our listing: What to learn while you need to reimagine household

Out Next Week

📚 All-Night Pharmacy, by Ruth Madievsky

Your Weekend Read

When Making Art Means Leaving the United States

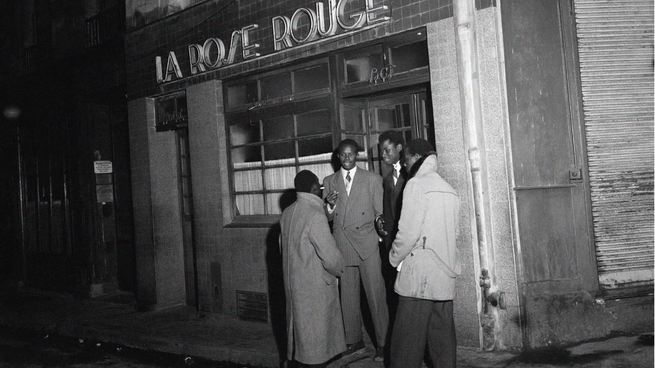

Tamara J. Walker describes the pillars of diasporic nightlife that earned elements of Nineteen Twenties Paris the nickname “French Harlem,” the place “patrons could dance to Martinican biguines, which derived from the folk songs of the enslaved, Senegalese orchestra tunes that included elements of Cuban music that traveled to African airways and migrated to France, and even some African American jazz” … With every story, Beyond the Shores builds a canon of Black artistic expression that crosses each temporal and geographic obstacles.

When you purchase a e book utilizing a hyperlink on this e-newsletter, we obtain a fee. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.