[ad_1]

I’m standing on prime of 100 meters of ice, watching a drone crisscross the Slakbreen glacier on Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, greater than 600 kilometers north of the mainland. I’m a part of a group testing Peregrine—a fixed-wing unmanned aerial car (UAV) geared up with miniaturized ice-penetrating radar, which may picture the glacial ice all the way in which right down to the bedrock beneath.

It’s –27 °C, dipping beneath –40 °C with wind chill—effectively beneath the working temperature of many of the business tools we introduced for this expedition. Our telephones, laptops, and cameras are quickly failing. The final of our computer systems that’s nonetheless working is sitting on prime of a small heating pad inside its personal little tent.

Harsh because the climate is right here, we intend for Peregrine to function in even harder circumstances, repeatedly surveying the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. These nice plenty retailer sufficient water to lift world sea stage by 65 meters ought to they soften completely. Although neither ice sheet is anticipated to soften fully anytime quickly, their unbelievable scale makes even small adjustments consequential for the way forward for our planet. And the information that Peregrine will collect will assist scientists to know how these vital areas will reply to local weather change.

Thomas Teisberg, {an electrical} engineering Ph.D. candidate at Stanford University, launches Peregrine at Norway’s Slakbreen glacier.

Getting beneath the floor

Scientists have lengthy checked out adjustments within the floor peak of ice sheets, utilizing knowledge collected from satellite-borne laser altimeters. This knowledge has come largely from

ICESat, launched in 2003, and its successor, ICESat-2, launched in 2018. With info from these NASA satellites, scientists measure the change in elevation, which they use to deduce the web influence of floor processes similar to snowfall and melting and the charges at which the ice sheets launch icebergs into the ocean.

These measurements are essential, to make sure, however laser altimetry gives no direct details about what’s occurring beneath the floor, together with how the ice deforms and the way it slides over the underlying rock.

And as we attempt to perceive how ice sheets are responding to new local weather extremes, these processes are key. How will adjustments in temperature influence the speed at which ice deforms beneath its personal weight? To what extent will liquid water reaching the underside of a glacier lubricate its mattress and trigger the ice to slip quicker into the ocean?

Getting solutions to those questions requires seeing beneath the floor. Enter ice-penetrating radar (IPR), a expertise that makes use of radio waves to picture the inner layers of glaciers and the mattress beneath them. Unlike different extra labor-intensive strategies, similar to drilling bore holes or establishing arrays of geophones to gather seismic knowledge, IPR programs from their earliest days have been flown on plane.

Peregrine lands after a take a look at flight in Norway.

In the Nineteen Sixties, as a part of a global collaboration, a U.S. Navy Lockheed C-130 Hercules transport was transformed into an IPR-data-collection plane. The challenge (which I’ll focus on in a bit of extra element in a confirmed that it was attainable to quickly accumulate this kind of knowledge from even essentially the most distant components of Antarctica. Since then, IPR devices have gotten higher and higher, as has the technique of analyzing the information and utilizing it to foretell future sea-level rise.

Meanwhile, although, the plane used to gather the information have modified comparatively little. Modern devices are sometimes flown on de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otters, that are two-engine turboprops, or Basler BT-67s, that are modified Douglas DC-3s. (Some Baslers flying missions in Antarctica right this moment flew World War II missions of their previous life.) And whereas help for these operations varies by nation, the demand for brand new knowledge is outpacing the power of crewed plane to gather it—not less than with a price ticket that doesn’t put it out of attain for all however essentially the most well-funded operations.

Collecting such knowledge right this moment simply shouldn’t be that tough.

That’s why I and different college students in Dustin Schroeder’s

Stanford Radio Glaciology lab are growing a number of novel ice-penetrating radar programs, together with Peregrine.

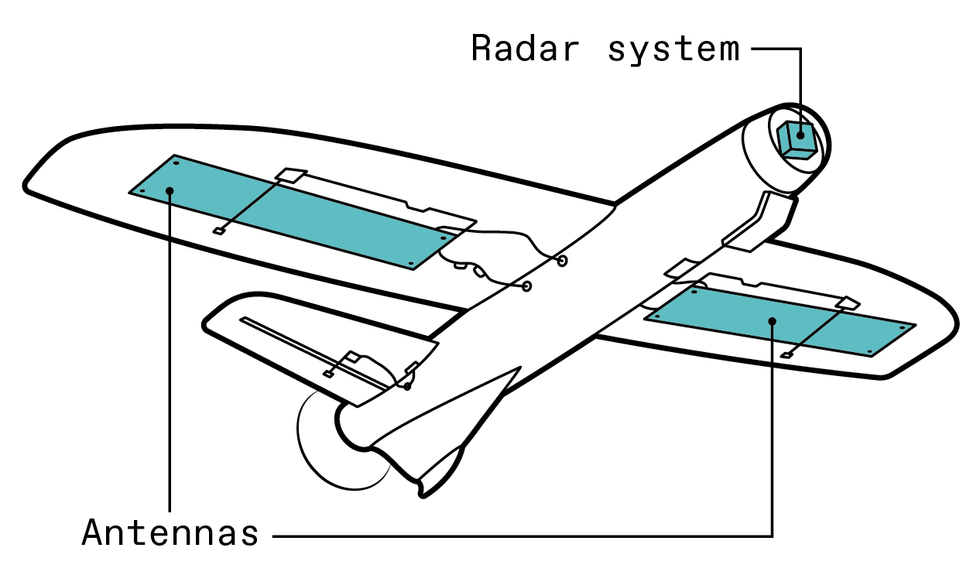

Peregrine is a modified UAV carrying a miniaturized ice-penetrating radar that we designed round a software-defined radio. The radar system weighs beneath a kilogram—featherweight in contrast with typical IPR programs, which take up complete tools racks in crewed plane. The complete bundle—drone plus radar system—prices just a few thousand {dollars} and packs right into a single ruggedized case, concerning the measurement of a big checked bag.

But to really perceive why we felt we have to get Peregrine out into the world now, you must know a bit concerning the historical past of knowledge gathering with ice-penetrating radar.

A satellite tv for pc failure creates a possibility for radar

The first large-scale IPR surveys of Antarctica started within the late Nineteen Sixties when a gaggle of American, British, and Danish geoscientists mounted a set of radar antennas beneath the wings of a C-130. Predating GPS, the challenge recorded flight paths utilizing inside navigation programs and identified floor waypoints. The system recorded radar returns utilizing a cathode-ray tube modified to scan over a passing reel of optical movie, which the researchers supplemented with handwritten notes. This effort produced tons of of rolls of movie and stacks of notebooks.

After the challenge led to 1979, numerous nationwide applications started finishing up regional surveys of each Antarctica and Greenland. Although they have been initially restricted in scope, these applications grew and, crucially, started to gather digitized knowledge tagged with GPS coordinates.

The Slakbreen glacier, situated on Norway’s Svalbard archipelago [enlarged view] within the coldest a part of the nation, was chosen for testing Peregrine as a result of it was unlikely to include liquid water, which might intrude with imaging of the bedrock beneath.

The Slakbreen glacier, situated on Norway’s Svalbard archipelago [enlarged view] within the coldest a part of the nation, was chosen for testing Peregrine as a result of it was unlikely to include liquid water, which might intrude with imaging of the bedrock beneath.

In the late 2000s, IPR surveying obtained an sudden increase. ICESat misplaced one laser altimeter after simply 36 days of knowledge assortment in 2003, and by late 2009 all of the satellite tv for pc’s lasers had stopped working. Laser altimetry’s issues would appear to have no connection to aircraft-based IPR surveys. But with ICESat-2 nonetheless years away from launching and a good political atmosphere for public earth-science funding within the United States, NASA organized

Operation IceBridge, a large-scale aircraft-based marketing campaign to cowl the laser-altimetry knowledge hole in Greenland and Antarctica.

Although the first objective was gathering laser altimetry, the usage of plane as a substitute of satellites meant that different devices could possibly be simply added. At the time, two U.S. establishments—

the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics and the Center for Remote Sensing and Integrated Systems (CReSIS) on the University of Kansas—had been growing improved IPR devices, so IPR was able to get on board.

Between 2009 to 2019, the plane of Operation IceBridge flew greater than 350,000 kilometers over the Antarctic whereas gathering IPR knowledge. During this similar interval, the

National Science Foundation’s Investigating the Cryospheric Evolution of the Central Antarctic Plate (ICECAP) program funded greater than 250,000 kilometers of extra Antarctic IPR knowledge.

Operation IceBridge enabled an enormous soar within the quantity of IPR knowledge collected worldwide. While different organizations all over the world additionally gathered and proceed to collect IPR knowledge, significantly

the British Antarctic Survey and the Alfred Wegener Institute, IceBridge took U.S.-led knowledge assortment from being nearly negligible in most years to being the primary supply of knowledge whereas the challenge was in operation.

As Peregrine climbs into the air over the Slakbreen glacier, the system’s purple antennas are clearly seen beneath the wings.Eliza Dawson

As Peregrine climbs into the air over the Slakbreen glacier, the system’s purple antennas are clearly seen beneath the wings.Eliza Dawson

In 2018, IceSat-2 launched, heralding the tip of Operation IceBridge. Some IPR surveying continued, however the price of knowledge assortment since 2018 has considerably lagged the scientific demand for such observations.

Adding to the necessity for higher ice-monitoring instruments is a current shift in the kind of IPR knowledge that scientists see as essential. Historically, these radar measurements have been used to determine the thickness of the ice above its mattress of rock or sediment.

Bed topography, with some exceptions, doesn’t change on time scales related to folks. So gathering this sort of IPR knowledge might typically be a one-time—or not less than rare—train, ending as soon as sufficient knowledge was gathered to construct a sufficiently detailed map of the mattress of a glacier or ice sheet.

But the depth of the ice to the mattress isn’t the one essential info hidden beneath the floor. For one, IPR knowledge reveals inside layering within the ice attributable to adjustments within the composition of the snow that fell. The form of those inside layers gives hints concerning the present and previous flows of the ice.

![Red and green solid lines, and a black dotted line, on a white background [left]. A black and white image that looks like a strip of paper bent to form a rough S-shape.](https://spectrum.ieee.org/media-library/red-and-green-solid-lines-and-a-black-dotted-line-on-a-white-background-left-a-black-and-white-image-that-looks-like-a-stri.jpg?id=34762242&width=980) Peregrine flew a sample [left, red line] spanning an space roughly 0.6 sq. kilometers over the Tellbreen glacier, additionally on the Svalbard archipelago. The drone’s ice-penetrating radar mapped the bottom beneath the glacier and likewise the layers inside it. The 3-D visualization [right] created from the information reveals these layers as faint strains and the bedrock as a brighter line.

Peregrine flew a sample [left, red line] spanning an space roughly 0.6 sq. kilometers over the Tellbreen glacier, additionally on the Svalbard archipelago. The drone’s ice-penetrating radar mapped the bottom beneath the glacier and likewise the layers inside it. The 3-D visualization [right] created from the information reveals these layers as faint strains and the bedrock as a brighter line.

Left: Chris Philpot; supply: Stanford Radio Glaciology Lab; Right: Thomas Teisberg

Scientists may also take a look at the reflectivity of the mattress, which may reveal the probability of liquid water being there. And the presence of water may give indications concerning the temperature of the encircling ice. The presence of water performs an important function in how briskly a glacier flows, as a result of water can lubricate the bottom of the glacier, inflicting extra speedy sliding and, consequently, quicker mass loss.

All of those are dynamic observations that will change on an annual and even seasonal foundation. So having only one radar survey each few years isn’t going to chop it.

Gathering extra frequent knowledge utilizing simply crewed flights is tough—they’re costly and logistically difficult, and, in harsh environments, they put folks in danger. The essential query about the way to change crewed plane is which course to go—up (a constellation of satellites) or down (a fleet of UAVs)?

A handful of satellites might present world protection and frequent repeat measurements over a few years, but it surely isn’t the perfect platform for ice-penetrating radar. To get the identical energy per unit space on the floor of the ice as a 1-watt transmitter on a UAV flying at an altitude of 100 meters, a satellite tv for pc in orbit at 400 kilometers would want a roughly 15-megawatt transmitter—that’s greater than thrice the utmost energy for which

SpaceX’s Starlink satellites have been licensed by the Federal Communications Commission.

Another problem is litter. Imagine you might have an antenna that emits energy primarily inside a 10-degree cone. You’re making an attempt to look at the underside of the ice sheet 1.5 km beneath the ice floor, however there’s a mountain vary 35 km away. From 400 km up, that mountain vary can also be being illuminated by your antenna and reflecting power again rather more strongly than the echo from the underside of the ice sheet, which is attenuated by the 1.5 km of ice it handed by every approach.

At the opposite finish of the spectrum of choices are UAVs, flying even nearer to the ice than crewed plane can. Researchers have been within the potential of UAV-borne radar programs for imaging ice for not less than a decade. In 2014, CReSIS fielded a 5-meter-wingspan radio-controlled plane with a miniaturized model of its IPR system. The design made intelligent use of the present wing geometry to supply low-frequency antennas, albeit with a small bandwidth that restricted knowledge high quality.

Since this pathfinding demonstration, a lot of the analysis focus has shifted to higher-frequency programs, generally known as

snow radars, designed to picture the close to floor to higher perceive mountain snowpacks, snow cowl on sea ice, and the layering construction within the prime few meters of ice sheets. CReSIS has examined its snow radar on a small autonomous helicopter; extra lately, it partnered with NASA and Vanilla Unmanned to fly its snow radar on an enormous 11-meter-wingspan UAV that may keep aloft for days at a time.

There’s nonetheless a necessity, although, for IPR imaging by ice sheets, with a excessive sufficient bandwidth to differentiate inside layers and a price ticket that enables for widespread use.

Enter Peregrine

The software-defined radio and different electronics that make up the ice-penetrating radar, shielded to keep away from interference with GPS alerts, sits within the nostril.Chris Philpot

The software-defined radio and different electronics that make up the ice-penetrating radar, shielded to keep away from interference with GPS alerts, sits within the nostril.Chris Philpot

Here’s the place Peregrine is available in. The challenge was began in 2020 to construct a smaller and extra inexpensive system than these tried beforehand, now made attainable by advances in fixed-wing UAVs and miniaturized electronics.

We knew we couldn’t do the IPR with off-the-shelf programs. We needed to begin with a clean slate to develop a system that was small and light-weight sufficient to suit on a reasonable UAV.

We determined to make use of software-defined radio (SDR) expertise for our radars as a result of these RF transmitters and receivers are extremely customizable and shift a lot of the complexity of the system from {hardware} to software program. Using an SDR, a whole radar system can match on a couple of small circuit boards.

From the beginning, we seemed past our first challenge, growing software program constructed on prime of

Ettus’s USRP Hardware Driver software programming interface, which can be utilized with quite a lot of software-defined radios, ranging in value from US $1,000 to $30,000 and in mass from tens of grams to a number of kilograms.

Thomas Teisberg huddles over a laptop computer laptop, partly shielded from the chilly by a small tent [left]. The tripod helps the radio used to speak with the drone. Later, Teisberg carries Peregrine again to the group after a take a look at flight [right]. The testing was carried out as a part of a field-based course supplied by the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS).

Thomas Teisberg huddles over a laptop computer laptop, partly shielded from the chilly by a small tent [left]. The tripod helps the radio used to speak with the drone. Later, Teisberg carries Peregrine again to the group after a take a look at flight [right]. The testing was carried out as a part of a field-based course supplied by the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS).

Eliza Dawson

We added a Raspberry Pi single-board laptop to manage our software-defined radio. The Raspberry Pi additionally connects to a community of temperature sensors, in order that we might make sure nothing in our system will get too sizzling or too chilly.

The SDR itself has two sides to it, one for transmitting the radar sign and one for receiving the echoes, every connecting to our custom-made antennas by amplifiers and filters. This complete system weighs a bit of beneath 1 kilogram.

Those antennas have been difficult to design. IPR antennas require comparatively low frequencies (as a result of increased frequencies are extra considerably attenuated by ice) and have comparatively vast bandwidths (to attain enough vary decision). Normally, these standards would imply a big antenna, however our small UAV couldn’t deal with a giant, heavy antenna.

I began by contemplating a normal bowtie antenna, a sort generally utilized in ground-based radar programs. The preliminary design was far too massive to suit even one antenna, a lot much less two, on our little UAV. So utilizing a digital mannequin of the antenna, I adjusted the geometry to search out a suitable compromise between measurement and efficiency, not less than in response to the simulation software program I used to be utilizing.

I additionally constructed a number of prototypes alongside the way in which to know how actual antenna efficiency may differ from my simulations. The first of these I constructed from copper tape reduce and pasted onto sheets of plastic. The later and ultimate variations I fabricated as printed circuit boards. After a couple of iterations, I had a working antenna that could possibly be mounted flat beneath every wing of our diminutive plane.

For the drone, we began with a equipment for an X-UAV Talon radio-controlled aircraft, which included a foam fuselage, tail meeting, and wings. We knew that each piece of conductive materials within the plane would have an effect on the antenna’s efficiency, maybe in undesirable methods. Tests confirmed that the carbon-fiber spar between the wings and the wires to the servo motors in every wing have been creating problematic conductive paths between the antennas, so we changed the carbon-fiber spar with a fiberglass one and added ferrite beads on the servo wiring to behave as low-pass filters.

Fighting noisy alerts

I believed we have been prepared. But after we took our UAV out to a area close to our lab, we found that we couldn’t get a GPS repair on the drone when the radar system was energetic. After some preliminary confusion, we found the supply of the interference: our system’s USB 3.0 interface. To clear up this drawback, I designed a plastic field to surround the

Raspberry Pi and the SDR, 3D-printed it, and wrapped it in a skinny layer of copper tape. That shielded the troublesome USB circuitry sufficient to maintain it from interfering with the remainder of our system.

Finally, we have been in a position to fly our tiny radar drone over a dry lakebed on the Stanford campus. Although our system can not picture by dust, we have been in a position to get a powerful reflection off the floor, and at that time we knew we had a working prototype.

![A man sits at a desk, one hand on computer keyboard and one hand on a mouse, looking at two computer displays. A copper colored box, that would fit in a hand, sits on the desk in front of the displays. [top] A computer visualization in two dimensions, in shades of purple, black, and yellow. Labels indicate u201cdistance to reflector,u201d u201cdistance,u201d and u201cpower.u201d](https://spectrum.ieee.org/media-library/a-man-sits-at-a-desk-one-hand-on-computer-keyboard-and-one-hand-on-a-mouse-looking-at-two-computer-displays-a-copper-colored.jpg?id=34785453&width=980) Thomas Teisberg critiques among the knowledge recorded by Peregrine. The small field on his desk with wires hooked up is a part of Peregrine’s payload, a bundle that features a software-defined radio, a Raspberry Pi, and different electronics wrapped in copper shielding. In this two-dimensional tracing of the information [above], the floor of the ice and form of the bedrock are clearly seen. Top: Thomas Tesiberg; Above: Mai Bui

Thomas Teisberg critiques among the knowledge recorded by Peregrine. The small field on his desk with wires hooked up is a part of Peregrine’s payload, a bundle that features a software-defined radio, a Raspberry Pi, and different electronics wrapped in copper shielding. In this two-dimensional tracing of the information [above], the floor of the ice and form of the bedrock are clearly seen. Top: Thomas Tesiberg; Above: Mai Bui

We carried out our first real-world assessments six months later, on Iceland’s Vatnajökull ice cap, because of the assistance and generosity of native collaborators at

the University of Iceland and a grant from NASA. That was a great place, as a result of on occasion, a close-by volcanic eruption spews volcanic materials often called tephra over the floor of the ice cap. That tephra ultimately will get buried beneath new snow and kinds a layer beneath the floor. We figured these strata would function a superb stand-in for the inner layering present in ice in Greenland and Antarctica. Although an abundance of liquid water within the comparatively heat Vatnajökull ice prevented our system from probing greater than tens of meters beneath the floor, these tephra layers have been obvious in our radar soundings.

But these first trials didn’t go uniformly effectively. After one among our take a look at flights, I found that the information we had collected was nearly completely noise. We examined each part and cable, till I discovered the defend on one of many coaxial cables had damaged and was solely intermittently making a connection. With a spare cable and a beneficiant software of sizzling glue, we have been in a position to full the remainder of our testing.

For our subsequent spherical of assessments, we have been aiming to picture bedrock beneath a glacier, not simply inside layers. And that’s why, in March of this yr, we ended up on a glacier within the coldest a part of Norway, the place liquid water throughout the ice was much less more likely to intrude with our measurements. There we have been in a position to picture the mattress of the glacier, as a lot as 150 meters beneath the floor the place we have been flying. Crucially, we additionally satisfied ourselves that our system will work correctly within the harsh environments we count on it to face in Antarctica and Greenland.

A drone fleet throughout Antarctica

Our current system is comparatively small. It was designed to be cheap and moveable in order that analysis groups can simply carry it alongside on expeditions to far-flung spots. But we additionally wished it to function a testbed for a bigger UAV-borne IPR system with an operational vary of about 800 km, one that’s cheap sufficient to be completely deployed to Antarctic analysis stations. With the 11 present analysis stations as bases, not less than one member of such a drone fleet might entry practically each a part of coastal Antarctica. Though bigger and dearer than our unique Peregrine, this next-generation UAV will nonetheless be far cheaper and simpler to function than crewed airborne programs are.

Operating a bigger UAV, a lot much less a fleet of them, is past what a couple of Ph.D. college students alone can moderately do, so we’re launching a collaborative effort between

Stanford University, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and Lane Community College, in Eugene, Ore., to get this new platform off the bottom. If all goes effectively, we’re hoping we are able to have IPR UAVs surveying the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets inside three years. Doing so would little doubt assist scientists learning the responses of Earth’s ice sheets to local weather change. With completely deployed UAVs in a position to cowl most areas of energetic research, requests for brand new knowledge could possibly be fulfilled inside days. Surveys could possibly be repeated at frequent intervals over dynamic areas. And when speedy and unpredictable occasions happen, such because the collapse of an ice shelf, a UAV could possibly be deployed to collect real-time radar knowledge.

Such observations are simply not attainable right this moment. But Peregrine and its successors might make that attainable. Having the power to gather this sort of radar knowledge would assist glaciologists resolve basic uncertainties within the physics of ice sheets, enhance projections of sea-level rise, and allow higher resolution making about mitigations and variations for Earth’s future local weather.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

[ad_2]