[ad_1]

Coming up with a brief checklist of books that seize the expertise of siblinghood is like attempting to find out the right names for six horses you’ve by no means met, or cooking a romantic dinner for a stranger with a number of undisclosed meals allergic reactions—an oddly private, high-stakes job. Every household is radically totally different in methods which are opaque to outsiders; the nuances of my relationship with my sibling might shed little mild in your relationship with yours.

In some methods, these bonds are like another: Mutual vulnerability, belief, and experiences can construct intimacy, although there isn’t a assure that that closeness will final. Yet the distinctive feeling of sharing mother and father, or of rising up collectively, makes this relationship in contrast to another. For many people, our hyperlinks with our siblings would be the longest of our lives. My mother and father all however superglued my brother and me collectively after we have been youngsters, insisting {that a} day might come when all now we have is one another.

My forthcoming novel, All-Night Pharmacy, is about two sisters with a detailed however poisonous bond, navigating addictions to prescribed drugs and to one another. I’ve at all times been drawn to books that seize a sure spirit of siblinghood: specifically, how our siblings can really feel much less like folks freely roaming the world than like extensions of our personal our bodies—a necessary organ or a wound, maybe each. These six books converse to the complexity of getting siblings, in all its rapture and mess.

If I Survive You, by Jonathan Escoffery

Escoffery’s debut assortment of linked tales is a story of biting sibling rivalry and a transferring household saga in regards to the immigrant expertise and dwelling between cultures in Miami. Our American-born protagonist, Trelawny, clashes together with his Jamaican-born older brother, Delano, of their disparate pursuits of monetary stability, parental love, and masculinity. Delano, the clear favourite, follows in his father’s footsteps by supporting his spouse and kids as a landscaper, whereas Trelawny pursues a university schooling. But after the recession, Trelawny’s diploma fails to guard him from dwelling out of his automotive and dealing a slew of precarious jobs (predatory constructing administration, Craigslist sexual race play). Escoffery is a wordsmith who retains us laughing at the same time as he runs his characters via capitalism’s meat grinder. “Oh, thank god,” Trelawny thinks upon receiving yet one more dying menace at work—this time within the type of an nameless drawing of a lynched man—and realizing it’s addressed to “El Jefe”: “I handed the paper to my manager and said, ‘It’s for you.’” When the siblings’ fortunes are flipped, Trelawny should resolve whether or not to be a greater brother to Delano than he’s been to him. The selection is a bitter one, laced with that exact ache that solely bone-deep disappointment engenders.

Black Aperture, by Matt Rasmussen

“Nothing ever absolutely has to happen,” Rasmussen writes on this poetry assortment, which circles the circumstances and aftermath of his brother’s suicide. “When our hero sits / on the edge of his bed contemplating the pistol / on his nightstand, you have to believe he might / not use it.” It’s a bitter paradox: We need to think about a world the place the gun may not fireplace, at the same time as Black Aperture reminds us that it might probably and can. Rasmussen resists schmaltz at each flip, choosing language so sharp and spare that you possibly can by no means accuse him of reaching for pathos. The poem “Reverse Suicide” inverts the sequence of occasions on the day of the suicide, echoing how trauma replays in our minds in surreal loops: “Each snowflake stirs before / lifting into the sky as I / learn you won’t be dead.” We don’t get a transparent sense of the connection the speaker and his brother had whereas he was alive. But the e book’s second poem, “After Suicide,” tells us the whole lot we have to know: “I wanted to put my finger / into the hole / feel the smooth channel / he escaped through.” The speaker’s acknowledgment that his brother wanted to flee his physique, coupled together with his need to review—or jam—the bullet gap anyway, smacked me like a brick.

Normal Family, by Chrysta Bilton

This memoir’s beautiful premise someway manages to not overshadow its beautiful prose. Bilton and her sister have been raised by a zany lesbian mom, who paid a good-looking stranger she met at a hair salon to donate his sperm to her. Bilton’s father, regardless of promising to not donate sperm to anybody else, secretly goes on to make his dwelling as one of many California Cryobank’s most requested donors. Bilton’s half siblings most likely quantity within the a whole lot, and she or he describes assembly 35 of them in her vibrant curler coaster of a e book. Her unpredictable however always-loving mom falls in with a number of cults, pyramid schemes, and addictions which have Bilton and her sister oscillating between dwelling in mansions with a menagerie of unique pets and straddling homelessness. There are completely ludicrous superstar encounters, anecdotes that push the nature-versus-nurture debate to extremes, and a bevy of unearthed household secrets and techniques (Bilton’s mom lastly spills the beans about Bilton’s half siblings after discovering that her daughter could also be courting her half brother). Normal Family will, in the perfect method, depart you questioning what both of these phrases really means.

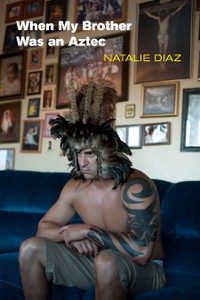

When My Brother Was an Aztec, by Natalie Diaz

In a 2015 dialog with the poetry-interview web site Divedapper, Diaz stated, “You can’t tell the truth because nobody will believe the truth if we tell it to them.” She advises her college students to reimagine their tales to permit the reader to raised glimpse their fact—from a slant. The fact, in Diaz’s case, highlights the colourful personalities she grew up with within the Fort Mojave Indian Village in Needles, California. Her debut poetry assortment, a few lady navigating need and the fracturing of her household as her brother falls deeper into meth dependancy, makes use of the fantastical to discover the tenderness and violence of affection in its many types. Judas; Mojave Barbie; and the half-man, half-hummingbird god Huitzilopochtli are among the many e book’s many supporting characters. Diaz’s signature darkish humor captures the absurdity of caring for somebody you’re dropping in actual time: “This is my brother and I need a shovel / to love him,” Diaz writes, shortly earlier than imagining his funeral. That’s adopted by half three of the e book, which comprises among the most sensual, aching odes to an unnamed beloved I’ve ever learn (“there is no apple, / there is only this woman / who is a city of apples, / there is only me licking the juice / from the streets of her palm”). I used to be shocked to study that Diaz was suggested to chop the items about need. When we finally return to the brother, we achieve this with the love poems’ reminder that, past our ache, there may be nonetheless a tomorrow.

All My Puny Sorrows, by Miriam Toews

This is the funniest e book you’ll ever examine a beloved sibling’s unquenchable need to finish her personal life. Toews’s tragicomic novel follows the narrator, Yoli, and her internationally acclaimed pianist sister, Elf, as they navigate an unresolvable deadlock: “She wanted to die and I wanted her to live and we were enemies who loved each other,” Toews writes. The sisters have been shut since their Mennonite childhood, throughout which, the narrator notes, “therapy was seen as lower even than bestiality because at least bestiality is somewhat understandable in isolated farming communities.” Where Black Aperture ruminates on the speaker’s powerlessness to stop his sibling’s suicide, All My Puny Sorrows affords its protagonist a daunting invitation. Elf asks Yoli to take her to a Swiss clinic that might help in ending her life, and Yoli should then resolve whether or not serving to Elf die can be the final word act of devotion. Off-kilter humor apart, All My Puny Sorrows is clear-eyed in its articulation of fierce sibling love. “I’m relieved that Elf wants her glasses,” Yoli thinks after certainly one of Elf’s suicide makes an attempt. “That there is something she wants to see.”

Win Me Something, by Kyle Lucia Wu

Wu’s enthralling debut novel follows a 24-year-old Chinese American lady named Willa, who makes a dwelling nannying Bijou, the 9-year-old daughter of a rich white household in New York. Willa’s mother and father divorced and began new households when she was a toddler, and Willa grew up feeling like a vestige of their previous lives. Willa’s unstated resentment over being deserted retains her relationship along with her three half siblings distant. Their absence is a gap in her life, and her tender take care of her cost—a proxy sister—is deeply affecting. Bijou’s household turn out to be surrogates for the loving and affluent dwelling life Willa was denied, however the match is awkward, as they’re clueless about Willa’s experiences with racism and their very own whiteness. Win Me Something reminds us that the narratives we inform ourselves may be simply as maladaptive as they’re self-protective. Wu masterfully implicates Willa in her failure to craft the life she longs for with out denying the traumas that result in her inaction. When, towards the top of the novel, Willa accepts her half sister’s invitation to have lunch, she realizes, “Maybe it wasn’t that everyone else was more loved, but that everyone else tried. Or that if you knew you were loved, it was easier to try.”

When you purchase a e book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.