[ad_1]

Waipapa Taumata Rau/University of Auckland

There’s not often time to write down about each cool science-y story that comes our manner. So this yr, we’re as soon as once more operating a particular Twelve Days of Christmas sequence of posts, highlighting one science story that fell by way of the cracks in 2022, every day from December 25 by way of January 5. Today: Scientists in New Zealand and Australia created tiny metallic snowflakes.

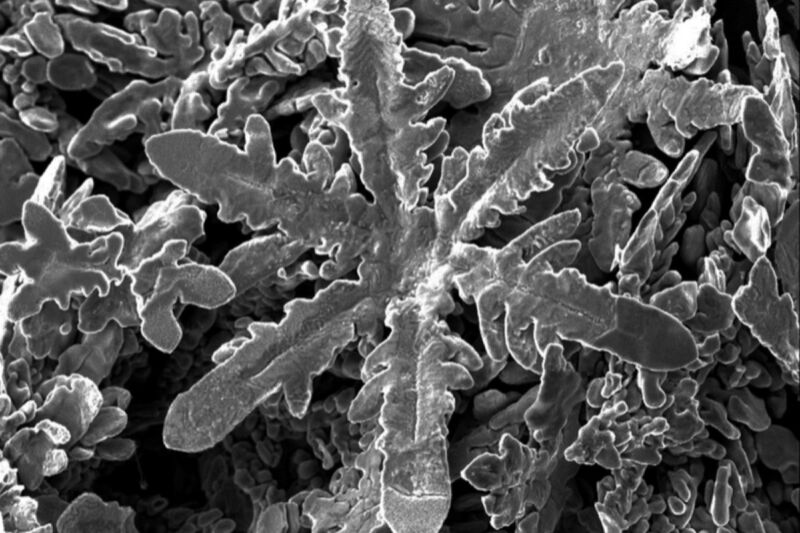

Scientists in New Zealand and Australia had been conducting atomic-scale experiments with numerous metals dissolved in liquid solvent of gallium once they observed one thing uncommon: several types of metallic self-assembled into totally different shapes of crystals—with zinc creating tiny metallic snowflakes. They described their leads to a paper printed earlier this month within the journal Science.

“In contrast to top-down approaches to forming nanostructure—by cutting away material—this bottom-up approaches relies on atoms self-assembling,” mentioned co-author Nicola Gaston of University of Auckland. “This is how nature makes nanoparticles, and is both less wasteful and much more precise than top-down methods. There’s also something very cool in creating a metallic snowflake!”

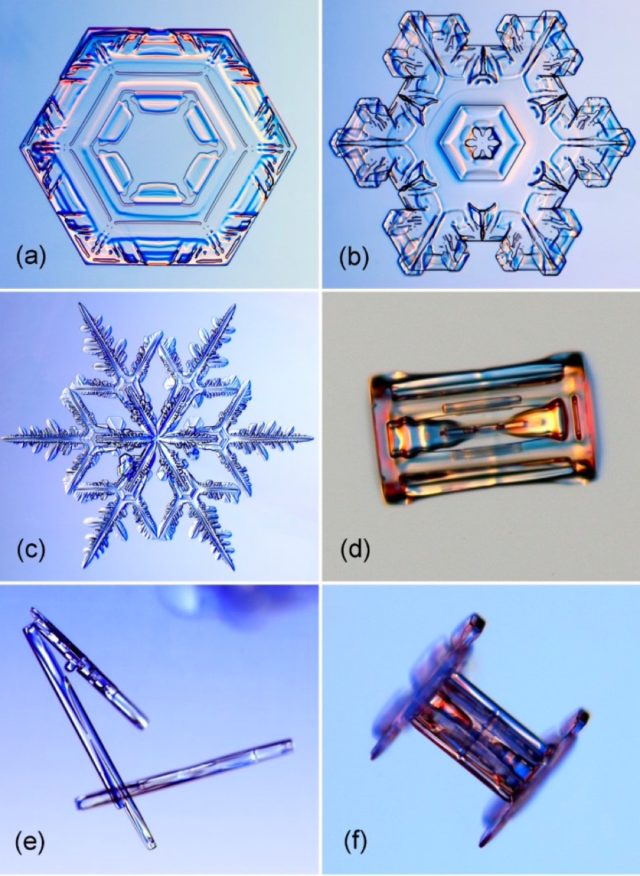

Snowflakes are the perfect recognized instance of crystal progress, at the least among the many common populace. It’s lengthy been recognized that beneath sure situations, water vapor can condense straight into tiny ice crystals, normally forming the form of a hexagonal prism (two hexagonal “basal” faces and 6 rectangular “prism” faces). But that crystal additionally attracts extra cooled water drops within the air. Branchings sprout out from the only crystals’ corners to kind snowflakes of more and more advanced shapes.

The shapes of snowflakes and snow crystals have lengthy fascinated scientists, like Johannes Kepler, who took a while away from his star-gazing in 1611 to publish a brief paper entitled “On the Six-Cornered Snowflake.” He was intrigued by the truth that snow crystals at all times appear to exhibit a six-fold symmetry. Some 20 years later, Rene Descartes waxed poetical after observing a lot rarer 12-sided snowflakes, “so completely fashioned in hexagons and of which the six sides had been so straight, and the six angles so equal, that it’s unattainable for males to make something so precise.” He contemplated how such a wonderfully symmetrical form might need been created, and ultimately arrived at a fairly correct description of the water cycle, including that “they had been obliged to rearrange themselves in such a manner that every was surrounded by six others in the identical airplane, following the abnormal order of nature.”

Robert Hooke’s Micrographia, printed in 1665, contained a number of sketches of snowflakes he noticed beneath his microscope. But no one carried out a very systematic research of snow crystals till the Nineteen Fifties, when a Japanese nuclear physicist named Ukichiro Nakaya recognized and cataloged all the foremost varieties of snow crystals. Nakaya was the primary particular person to develop synthetic snow crystals within the laboratory. In 1954 he printed a ebook on his findings: Snow Crystals: Natural and Artificial.

Watch a snowflake “develop” into an intricate crystal construction. Credit: Kenneth Libbrecht

Thanks to Nakaya’s pioneering work, we all know that sure atmospheric situations, like temperature and humidity, can affect a snowflake’s form. Star-like shapes kind at -2 levels Celsius and -15 levels Celsius, whereas columns kind at -5 levels Celsius and once more at round -30 levels Celsius. And the upper the humidity, the extra advanced the form. If the humidity is very excessive, they will even kind into lengthy needles or giant skinny plates.

Kenneth Libbrecht, a physicist at Caltech, has been learning and photographing the formation of snowflakes for greater than 20 years. And like Nakaya, he additionally creates his personal snowflakes within the lab, fastidiously utilizing a small paintbrush to switch the fragile buildings to a glass slide, taking photos with a digital digital camera mounted on a high-resolution microscope. He has documented the numerous sorts of snow crystals over the all these years, culminating in a 540-page monograph that has been referred to as a tour de power of snowflake physics.

Most just lately, in 2019, Libbrecht developed what he termed a “semi-empirical” mannequin of the atomic processes at work to clarify why there are two major varieties of snowflakes: the long-lasting flat star, with both six or 12 factors, and a column, typically sandwiched by flat caps and typically resembling a bolt from a ironmongery store. Libbrecht wished to discover exactly what adjustments with the shifts in temperature. His mannequin incorporates a phenomenon referred to as surface-energy-driven molecular diffusion. Per Quanta:

A skinny, flat crystal (both plate-like or starlike) kinds when the sides rope in materials extra shortly than the crystal’s two faces. The burgeoning crystal will unfold outward. However, when its faces develop sooner than its edges, the crystal grows taller, forming a needle, hole column or rod. According to Libbrecht’s mannequin, water vapor first settles on the corners of the crystal, then diffuses over the floor both to the crystal’s edge or to its faces, inflicting the crystal to develop outward or upward, respectively. Which of those processes wins as numerous floor results and instabilities work together relies upon totally on temperature.

Kenneth Libbrecht

With this newest work, Gaston and her colleagues prolonged the analogy of ice snowflakes to metals. They dissolved samples of nickel, copper, zinc, tin, platinum, bismuth, silver, and aluminum in gallium, which turns liquid at simply above room temperature, making it a superb liquid solvent for the experiments. Once every thing cooled, the metallic crystals fashioned however the gallium remained liquid. They had been capable of extract the metallic crystals by decreasing the floor pressure of the gallium solvent—achieved through a mixture of electrocapillary modulation and vacuum filtration—and punctiliously documented the totally different morphologies of every.

Next they performed simulations of the molecular dynamics to find out why totally different metals produced in another way formed crystals: cubes, rods, hexagonal plates, and within the case of zinc, a snowflake construction. They discovered that all of it comes all the way down to the interactions between the atomic construction of the metals and the liquid gallium. “What we are learning is that the structure of the liquid gallium is very important,” mentioned Gaston. “That’s novel because we usually think of liquids as lacking structure or being only randomly structured.”

DOI: Science, 2022. 10.1126/science.abm2731 (About DOIs).

Listing picture by Waipapa Taumata Rau/University of Auckland

[ad_2]