I hate the attention pressure that always comes with peering by way of a telescope on the night time sky—I’d relatively let a digicam seize the scene. But I’m too frugal to sink 1000’s of {dollars} into high-quality astrophotography gear. The Goldilocks answer for me is one thing that goes by the identify of electronically assisted astronomy, or EAA.

EAA occupies a center floor in novice astronomy: extra concerned than gazing by way of binoculars or a telescope, however not as difficult as utilizing specialised cameras, costly telescopes, and motorized monitoring mounts. I set about exploring how far I might get doing EAA on a restricted funds.

Electronically-assisted-astronomy pictures captured with my rig: the moon [top], the solar [middle], and the Orion Nebula [bottom] David Schneider

Electronically-assisted-astronomy pictures captured with my rig: the moon [top], the solar [middle], and the Orion Nebula [bottom] David Schneider

First, I bought a used Canon T6 DSLR on eBay. Because it had a broken LCD viewscreen and got here and not using a lens, it price simply US $100. Next, relatively than making an attempt to marry this digicam to a telescope, I made a decision to get a telephoto lens: Back to eBay for a 40-year-old Nikon 500-mm F/8 “mirror” telephoto lens for $125. This lens combines mirrors and lenses to create a folded optical path. So despite the fact that the focal size of this telephoto is a whopping 50 centimeters, the lens itself is simply about 15 cm lengthy. A $20 adapter makes it work with the Canon.

The Nikon lens lacks a diaphragm to regulate its aperture and therefore its depth of subject. Its optical geometry makes issues which are out of focus resemble doughnuts. And it might’t be autofocused. But these shortcomings aren’t drawbacks for astrophotography. And the lens has the large benefit that it may be targeted past infinity. This lets you modify the deal with distant objects precisely, even when the lens expands and contracts with altering temperatures.

Getting the main focus proper is without doubt one of the bugaboos of utilizing a telephoto lens for astrophotography, as a result of the deal with such lenses is sensitive and simply will get knocked off kilter. To keep away from that, I constructed one thing (primarily based on a design I discovered in a web-based astronomy discussion board) that clamps to the main focus ring and permits exact changes utilizing a small knob.

My subsequent buy was a modified gun sight to make it simpler to goal the digicam. The model I purchased (for $30 on Amazon) included an adapter that permit me mount it to my digicam’s scorching shoe. You’ll additionally want a tripod, however you should buy an enough one for lower than $30.

Getting the main focus proper is without doubt one of the bugaboos of utilizing a telephoto lens

The solely different {hardware} you want is a laptop computer. On my Windows machine, I put in 4 free applications: Canon’s EOS Utility (which permits me to regulate the digicam and obtain photographs immediately), Canon’s Digital Photo Professional (for managing the digicam’sRAW format picture information), the GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP) picture editor, and a program known asDeep Sky Stacker, which lets me mix short-exposure photographs to reinforce the outcomes with out having Earth’s rotation smash issues.

It was time to get began. But specializing in astronomical objects is more durable than you would possibly suppose. The apparent technique is to place the digicam in “live view” mode, goal it at Jupiter or a brilliant star, after which modify the main focus till the article is as small as doable. But it might nonetheless be arduous to know while you’ve hit the mark. I bought an enormous help from what’s often called a Bahtinov masks, a display screen with angled slats you briefly stick in entrance of the lens to create a diffraction sample that guides focusing.

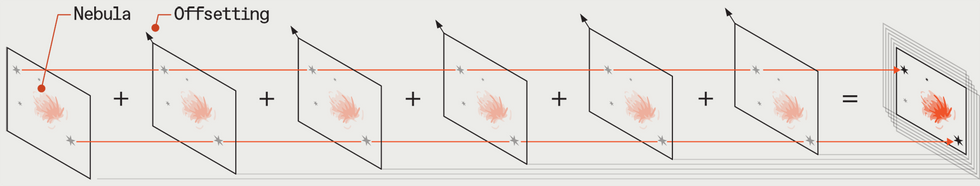

Stacking software program takes a collection of photographs of the sky, compensates for the movement of the celebrities, and combines the pictures to simulate lengthy exposures with out blurring.

Stacking software program takes a collection of photographs of the sky, compensates for the movement of the celebrities, and combines the pictures to simulate lengthy exposures with out blurring.

After getting some good pictures of the moon, I turned to a different straightforward goal: the solar. That required a photo voltaic filter, after all. Ibought one for $9 , which I minimize right into a circle and glued to a sweet tin from which I had minimize out the underside. My tin is of a measurement that slips completely over my lens. With this filter, I used to be in a position to take good photographs of sunspots. The problem once more was focusing, which required trial and error, as a result of methods used for stars and planets don’t work for the solar.

With focusing down, the following hurdle was to picture a deep-sky object, or DSO—star clusters, galaxies, and nebulae. To picture these dim objects very well requires a monitoring mount, which turns the digicam with the intention to take lengthy exposures with out blurring from the movement of the Earth. But I needed to see what I might do and not using a tracker.

I first wanted to determine how lengthy of an publicity was doable with my mounted digicam. A standard rule of thumb is to take the focal size of your telescope in millimeters and divide by 500 to provide the most publicity length in seconds. For my setup, that will be 1 second. A extra refined strategy, known as the NPF rule, components in extra particulars relating to your imaging sensor. Using anon-line NPF-rule calculator gave me a barely decrease quantity: 0.8 seconds. To be much more conservative, I used 0.6-second exposures.

My first DSO goal was the Orion Nebula, of which I shot 100 photographs from my suburban driveway. No doubt, I’d have executed higher from a darker spot. I used to be aware, although, to accumulate calibration frames—“flats” and “darks” and “bias images”—that are used to compensate for imperfections within the imaging system. Darks and bias photographs are straightforward sufficient to acquire by leaving the lens cap on. Taking flats, nonetheless, requires a fair, diffuse mild supply. For that I used a $17 A5-size LED tracing pad positioned on a white T-shirt protecting the lens.

With all these photographs in hand, I fired up the Deep Sky Stacker program and put it to work. The resultant stack didn’t look promising, however postprocessing in GIMP turned it right into a surprisingly detailed rendering of the Orion Nebula. It doesn’t examine, after all, with what anyone can do with a greater gear. But it does present the sorts of fascinating photographs you may generate with some free software program, an peculiar DSLR, and a classic telephoto lens pointed on the proper spot.

This article seems within the May 2024 print difficulty as “Electronically Assisted Astronomy.”