Welcome to Up for Debate. Each week, Conor Friedersdorf rounds up well timed conversations and solicits reader responses to 1 thought-provoking query. Later, he publishes some considerate replies. Sign up for the e-newsletter right here.

Question of the Week

What is essentially the most constructive approach for the press to cowl race if its aims embody precisely informing residents in regards to the previous and the current––regardless of how terrible or uncomfortable––and refraining from framing the information in methods which are needlessly polarizing or essentialist?

Send your responses to conor@theatlantic.com.

Conversations of Note

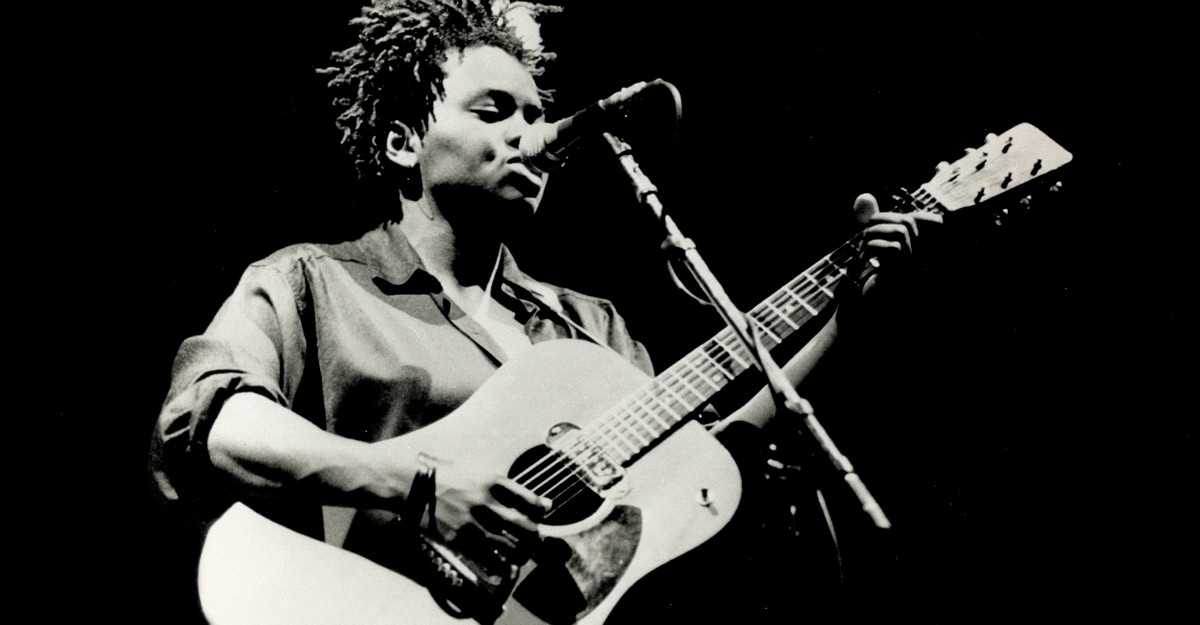

On April 6, 1988, the singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman launched a self-titled album that ranks among the many greatest debuts––hell, the very best albums––ever, largely due to the singles “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution,” the demo of which obtained her the document deal, and “Fast Car.” Summon each flawless lyric and guitar riff to your thoughts’s ear, or else go stream it now.

How simple was this album and its greatest hit single? Within its first two weeks, Tracy Chapman offered 1 million copies. It peaked at No. 1 on the U.S. Billboard 200. It has been licensed platinum six instances over. It was nominated for six Grammys, together with Album of the Year. Chapman received three: Best Contemporary Folk Album, Best New Artist, and Best Female Pop Vocal Performance for “Fast Car.” The album warranted famous person acclaim and riches for its theretofore unknown creator––and it obtained them from the beginning.

In a testomony to the music’s broad attraction and timelessness, Tracy Chapman and “Fast Car” additionally rocketed to No. 1 in a number of overseas international locations, and on occasion, when a brand new technology discovers it, lightning strikes once more. In 2011, “Fast Car” reached No. 4 on the U.Okay. Singles Chart when it was coated on Britain’s Got Talent. And this 12 months, when the nation singer Luke Combs launched a canopy of the tune, it rocketed to No. 1 on the Country Songwriters Chart. Shortly after, Chapman herself launched a press release to Billboard. “I never expected to find myself on the country charts, but I’m honored to be there,” she mentioned. “I’m happy for Luke and his success and grateful that new fans have found and embraced ‘Fast Car.’” Billboard stories that the duvet has earned Chapman roughly $500,000 in publishing royalties to date. Rolling Stone notes that she would be the first Black girl “to have the sole songwriting credit on a Number One country hit.”

Progress!

“Fast Car” is a gritty and heartbreaking tune that faucets into our shared humanity whereas exploring poverty, dependancy, hope, disappointment, and craving––listening to it, even for the thousandth time, one is reminded anew how robust so many have it proper now. And but the tune’s success is a feelgood story of outstanding artwork acknowledged and lavishly rewarded, repeatedly, whereas bringing individuals of all kinds collectively throughout cultures, nations, and generations.

Or is it?

Problematizing the “Fast Car” Story

Last week, the Washington Post Style-section reporter Emily Yahr printed an article titled “Tracy Chapman, Luke Combs and the Complicated Response to ‘Fast Car.’” Its focus is as follows:

To fairly a number of individuals, [the cover recording’s success] is trigger for yet one more celebration in Combs’s whirlwind journey as the style’s reigning megastar with 16 consecutive No. 1 hits. But it has additionally prompted a wave of sophisticated emotions amongst some listeners and within the Nashville music neighborhood. Although many are thrilled to see “Fast Car” again within the highlight and a brand new technology discovering Chapman’s work, it’s clouded by the truth that, as a Black queer girl, Chapman, 59, would have nearly zero probability of that achievement herself in nation music. The numbers are bleak: A latest research by knowledge journalist Jan Diehm and musicologist Jada Watson reported that fewer than 0.5 % of songs performed on nation radio in 2022 have been by girls of colour and LGBTQ+ artists. Watson’s earlier work exhibits that songs by girls of colour and LGBTQ+ artists have been largely excluded from radio playlists for many of the 20 years prior.

Very rapidly, the Post article grew to become a kind of polarizing mainstream-media tales that stokes eye-rolling and mockery on social media and podcasts, in addition to passionate defenses from individuals who regard the unfavourable responses as reactionary.

Here’s a pattern of Twitter reactions to the Post story:

Noah Smith: “Man just let people sing a song. Making every piece of entertainment into a race war is just utterly exhausting.”

Varad Mehta: “This is incoherent. Tracy Chapman’s not a country artist. So of course she’s not going to place on the country charts. And as everyone has pointed out, Chapman’s original did great on the pop and mainstream charts. Which is a lot better than doing well on the country charts.”

Nadia Gill: “Isn’t the takeaway that art is not to be emotionally possessed. That it can be universal. That a black lesbian and a straight white man may feel the same depth and story despite identity differences. What if we pushed that narrative.”

Free Black Thought: “A really great thing happens for an already deservedly successful black LGBT woman and all the @washingtonpost can do is talk about how no black person can ever make it in America.”

Into the Fray

I weighed in, too, reiterating a long-standing concern: Most information occasions could be framed in any variety of methods, and within the media right now, many journalists consider they advance social justice by selecting frames that heart the racial identities of their topics. However, the impact of so regularly emphasizing racial identification could be to extend interracial antagonism and bigoted othering, because the individuals least psychologically comfy with distinction are reaffirmed day by day of their false and pernicious conceit that folks of various races are “others” somewhat than “one of us.”

I’m notably involved about overemphasizing racial identification as a result of political-psychology analysis on individuals with a predisposition to authoritarianism exhibits that who they contemplate to be an “other” is definitely fairly malleable; everybody in society advantages when would-be authoritarians regard race as a much less salient attribute. But many progressives are so averse to that concern that they don’t even wrestle with the analysis literature underpinning it, as an alternative treating the priority itself as reactionary. The sociologist Victor Ray responded to my tweet: “A faction of reactionary centrists and conservatives downplay the importance of race in every corner of American life, ensuring traditional hierarchies are never challenged.”

To defenders of the Washington Post article extra usually, it was a well timed, necessary have a look at the factually simple dearth of queer Black girls in nation music, and the criticism of it confirmed that many Americans are reflexively averse to confronting racism, a lot in order that they lash out at anybody who tries to make clear racial inequity. And certain, some Americans are like that.

To me, nonetheless, it appears self-evident that, due to ongoing racial inequity, it’s attainable to speak too little about race and racism; however that, simply as certainly, as a result of race is a false and pernicious assemble of slavers and bigots, it’s attainable to raise its salience and to emphasise it an excessive amount of. What’s extra, a reflexive unwillingness to confront racism isn’t credibly behind all criticism of the left-identitarian strategy to discussing race, as handy as that uncharitable evaluation can be to the progressives whose strategy is being criticized.

Among critics of the Post article, many––together with me––have additionally printed and endorsed scores of journalistic efforts that spotlight racism and problem bigoted hierarchies. Why did the Post story vex individuals in a approach that so many different articles about race or racism didn’t? Here’s my greatest effort to elucidate my response––and insofar as you disagree, I hope you’ll push again by way of e mail.

Fitting Facts to Theory or Theory to Facts?

It might shock a few of you, at this level, to study that I’d be glad to learn a function on nation music because it intersects with race and sexual orientation. What are the small print of this fraught historical past? How many Black girls and what number of LGBTQ individuals are making an attempt to make it on the nation charts? How diversified are their experiences? The Post mentions that within the early twentieth century, Black singers “were filtered out of the genre.” Are Black girls getting rejected by style gatekeepers right now? Are they being steered elsewhere by managers or self-selecting out of the style due to discrimination, worry of prejudice, and/or advanced business issues? If one might select amongst totally different style charts, by way of status or attain or remuneration, which charts are thought-about by insiders to be the very best and the worst? To what diploma do patrons and streamers of nation music eat music in different genres? I’ve no robust priors on these and different fascinating questions and am open to any well-argued conclusion.

Now distinction that hypothetical article––interrogating advanced questions by marshaling information with nuance and arguing to a thought-about conclusion––with the Post article’s strategy to the topic. At its heart is the truth that only a few queer Black girls succeed on the nation charts. In place of nuanced reporting and evaluation on why that’s so, the story presumes that the success of the “Fast Car” cowl on the nation charts tells us one thing vital about that dearth of illustration, and though that vital factor isn’t exactly articulated, it has one thing to do with racism and the place of queer Black girls on the backside of the intersectional hierarchy.

In the Post article, one Black country-music singer-songwriter, Rissi Palmer, is quoted praising Tracy Chapman’s work, however we by no means hear from any queer or Black songwriters describing their very own experiences making an attempt to work in nation music, tales that might higher inform us in regards to the article’s core topic. Instead, we hear from cultural observers who share their emotions about what the Luke Combs cowl supposedly tells us. The author doesn’t push them to have interaction with apparent counters to their perspective. And we don’t hear from analysts with complicating or countervailing views. Why not embody a voice who regards the duvet as unproblematic?

The result’s a one-sided evaluation that begs loads of questions. I believe the backlash to the Post story is basically rooted in the truth that the success of a “Fast Car” cowl is an inapt peg for a narrative a few dearth of queer Black girls succeeding on the country-music charts. Chapman is a wildly profitable musician, she has by no means been a rustic singer, and nobody ever thought-about “Fast Car” a rustic tune. To select the “Fast Car” information peg for an exploration of queer Black exclusion forces the article to proceed not with actual tales of the dynamics of race and sexual orientation in nation music, however with speculative hypotheticals about the way it feels like identification capabilities.

Here, examples are helpful. Holly G, founding father of the Black Opry, a company for Black nation music singers and followers, is quoted telling the Post: “On one hand, Luke Combs is an amazing artist, and it’s great to see that someone in country music is influenced by a Black queer woman—that’s really exciting. But at the same time, it’s hard to really lean into that excitement knowing that Tracy Chapman would not be celebrated in the industry without that kind of middleman being a White man.” But can we “know” that Chapman wouldn’t be celebrated in a hypothetical the place she emerged right now and tried launching “Fast Car” on the nation charts? No extra, I believe, than we “knew” what would occur if the Black frontman of Hootie and the Blowfish reinvented himself as a rustic singer and coated the outdated customary “Wagon Wheel.” (Here’s a Billboard article about Darius Rucker stopping by the Country Music Hall of Fame and receiving a plaque to commemorate his cowl going platinum eight instances over.)

Another part of the Post story airs the speculative concern that Combs would possibly overshadow Chapman:

Jake Blount, an Afrofuturist people artist who has devoted his profession to learning music historical past and reinterpreting older songs, tweeted in regards to the concern of Chapman’s “legacy being overwritten in real-time.” He thought of how Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog” was consumed by Elvis Presley or how Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe McCoy’s “When the Levee Breaks” was overshadowed by Led Zeppelin, together with limitless different examples of the “White male genius” archetype that always receives credit score for songs by Black artists.

“When I wrote those tweets, people [replied] to me and said, ‘Oh, there’s no way anybody’s going to forget Tracy Chapman, she’s too big already.’ … And I hope that’s true, but I know how it’s played out before,” Blount mentioned. “We know Black visionaries who have created incredible, powerful, influential works … that have been forgotten and erased. It’s not malice from the White artists making derivative music based on theirs, but it’s how society works.”

Is that “how society works”? With full acknowledgment of the numerous Black recording artists short-shrifted by racism, our society has lengthy been a lot extra sophisticated than that. To cite one related instance, Whitney Houston’s cowl of “I Will Always Love You” has far overshadowed the unique Dolly Parton nation model. Sometimes, our society works that approach, too. And whereas I can think about a future case the place a white man data a canopy that overshadows a Black girl’s authentic tune, it appears apparent to me that on this case, there may be nearly zero probability that the Combs model of “Fast Car” will overshadow, and even remotely strategy in success, the Chapman model.

I used to be additionally struck by the newspaper’s parenthetical: “Chapman does not discuss her personal life, but writer Alice Walker has disclosed their relationship, which occurred in the 1990s.” To me, that solely underscores the weirdness of the article’s reliance on hypotheticals. So Chapman’s reported “queerness” would have given her nearly zero probability of succeeding within the Eighties nation music scene as a result of, someday in the subsequent decade, a well-known creator would out her as having had a same-sex relationship? Maybe! I don’t doubt that queer Black girls confronted prejudice in Eighties nation music. But Chapman’s sexuality was not being mentioned on the time. Moreover, Chapman didn’t face prejudice––certainly, she skilled nothing in any respect, good or dangerous––as a nation music recording artist, so why is that what I’m studying about within the Post? Isn’t there sufficient injustice on the planet with out speculating about hypothetical bygone oppressions?

A Difficult Calibration

Emily Yahr, the creator of the Post article, is taking unfair grief and abuse for misreadings of her thesis, as all the time occurs when articles go viral. What’s extra, the query of methods to greatest calibrate the relevance of race to information tales in a multiethnic democracy is massively troublesome to reply. Perspectives will differ, as will judgments in particular person situations, and totally different individuals are entitled to their opinions, which oughtn’t topic them to unconstructive digs or vilification.

But insofar as the concept behind this form of protection is that it advances social justice by speaking about racism––backlash be damned, as a result of speaking about racism is necessary––I’ve a query: In a world of solipsistic information customers, who report fatigue when any drawback is roofed usually, would possibly or not it’s greatest if journalism writ giant targeted its protection of racism on comparatively consequential real-world examples, somewhat than, for instance, the truth that some nation followers fear a Black girl’s model of “Fast Car” is perhaps overshadowed by a white man’s cowl, although the Black girl’s model stays rather more profitable proper now?

Ultimately I’m not averse to shut, uncomfortable, detailed journalism about racism––however I’m averse to speculative hypotheticals about racism that will have theoretically occurred, however didn’t, not less than after they come within the context of taking the inspiring and heartening historical past of a Black folk-rock artist succeeding tremendously in Eighties America and reframing her precise, ongoing success as a feel-dangerous story about how a lot much less profitable she would have been than a white man. Especially provided that Chapman is, in actuality, extra profitable than that white man, what sort of racism or racists are these speculative eventualities about Tracy Chapman diminishing? And we’d like not body identification in the best way this remaining excerpt from the Post story did:

Holly of the Black Opry mentioned that now can be a good time for Combs to ask a queer Black feminine artist to hitch him on tour or to supply his assist: “You used her art to enrich your career, and that opens you up to a little bit of responsibility giving back to the community.”

Set apart this corrosively zero-sum characterization of a canopy that benefitted Chapman, by her personal account. As I see it, Chapman, a singular and singularly gifted particular person, wrote “Fast Car,” not the Black neighborhood, or the queer neighborhood, or a collective encompassing all Black feminine artists. To me, Combs can be responsible of tokenization if he discovered a queer Black girl and mentioned, “I covered a song by someone with your skin tone and sexual orientation; want to join me on tour?” I might cheer affirmative efforts by profitable nation musicians to diversify their style, however the racecraft quoted above is incompatible with a world the place individuals of various races are equals in a beloved neighborhood, not “others.” At the identical time, I respect that Holly of the Black Opry is making an attempt to do good as she sees it, and I want her success in a lot of her challenge, not least as a result of I’m excited to see the primary Black feminine nation star.

That’s all for right now––see you subsequent week.

Thanks on your contributions. I learn each one that you simply ship. By submitting an e mail, you’ve agreed to allow us to use it—partly or in full—within the e-newsletter and on our web site. Published suggestions might embody a author’s full identify, metropolis, and state, until in any other case requested in your preliminary observe, and could also be edited for size and readability.