[ad_1]

Imagine you’re scrolling via the photographs in your cellphone and also you come throughout a picture that in the first place you’ll be able to’t acknowledge. It seems to be like perhaps one thing fuzzy on the sofa; might it’s a pillow or a coat? After a few seconds it clicks — in fact! That ball of fluff is your buddy’s cat, Mocha. While a few of your photographs may very well be understood right away, why was this cat picture way more tough?

MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) researchers have been stunned to seek out that regardless of the essential significance of understanding visible knowledge in pivotal areas starting from well being care to transportation to family gadgets, the notion of a picture’s recognition issue for people has been nearly solely ignored. One of the most important drivers of progress in deep learning-based AI has been datasets, but we all know little about how knowledge drives progress in large-scale deep studying past that larger is best.

In real-world functions that require understanding visible knowledge, people outperform object recognition fashions although fashions carry out nicely on present datasets, together with these explicitly designed to problem machines with debiased pictures or distribution shifts. This drawback persists, partially, as a result of we’ve no steerage on absolutely the issue of a picture or dataset. Without controlling for the problem of pictures used for analysis, it’s arduous to objectively assess progress towards human-level efficiency, to cowl the vary of human talents, and to extend the problem posed by a dataset.

To fill on this data hole, David Mayo, an MIT PhD scholar in electrical engineering and laptop science and a CSAIL affiliate, delved into the deep world of picture datasets, exploring why sure pictures are tougher for people and machines to acknowledge than others. “Some pictures inherently take longer to acknowledge, and it is important to know the mind’s exercise throughout this course of and its relation to machine studying fashions. Perhaps there are complicated neural circuits or distinctive mechanisms lacking in our present fashions, seen solely when examined with difficult visible stimuli. This exploration is essential for comprehending and enhancing machine imaginative and prescient fashions,” says Mayo, a lead creator of a brand new paper on the work.

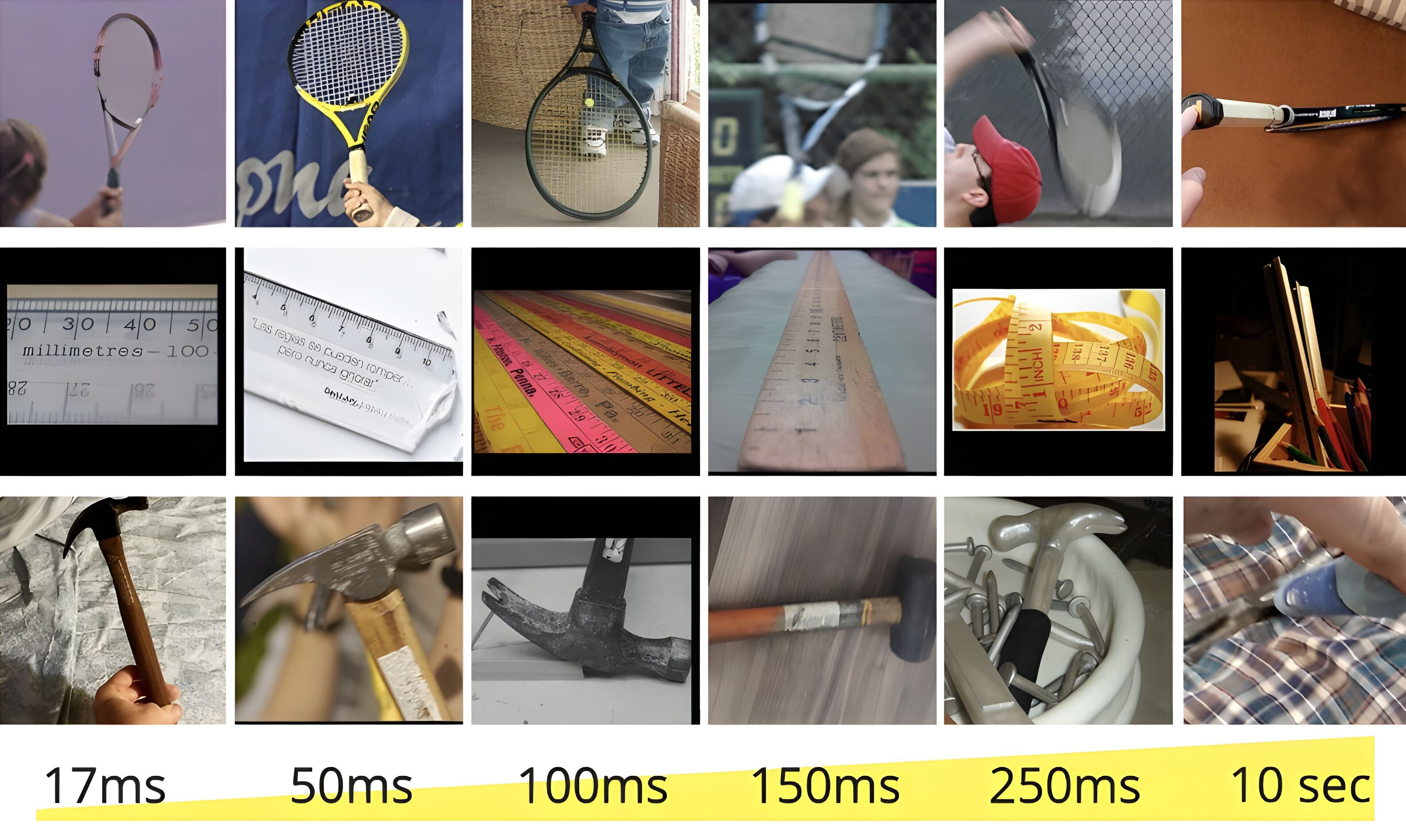

This led to the event of a brand new metric, the “minimum viewing time” (MVT), which quantifies the problem of recognizing a picture based mostly on how lengthy an individual must view it earlier than making an accurate identification. Using a subset of ImageWeb, a well-liked dataset in machine studying, and ObjectNet, a dataset designed to check object recognition robustness, the crew confirmed pictures to contributors for various durations from as brief as 17 milliseconds to so long as 10 seconds, and requested them to decide on the proper object from a set of fifty choices. After over 200,000 picture presentation trials, the crew discovered that current take a look at units, together with ObjectNet, appeared skewed towards simpler, shorter MVT pictures, with the overwhelming majority of benchmark efficiency derived from pictures which can be simple for people.

The venture recognized attention-grabbing traits in mannequin efficiency — significantly in relation to scaling. Larger fashions confirmed appreciable enchancment on easier pictures however made much less progress on tougher pictures. The CLIP fashions, which incorporate each language and imaginative and prescient, stood out as they moved within the course of extra human-like recognition.

“Traditionally, object recognition datasets have been skewed towards less-complex images, a practice that has led to an inflation in model performance metrics, not truly reflective of a model’s robustness or its ability to tackle complex visual tasks. Our research reveals that harder images pose a more acute challenge, causing a distribution shift that is often not accounted for in standard evaluations,” says Mayo. “We released image sets tagged by difficulty along with tools to automatically compute MVT, enabling MVT to be added to existing benchmarks and extended to various applications. These include measuring test set difficulty before deploying real-world systems, discovering neural correlates of image difficulty, and advancing object recognition techniques to close the gap between benchmark and real-world performance.”

“One of my biggest takeaways is that we now have another dimension to evaluate models on. We want models that are able to recognize any image even if — perhaps especially if — it’s hard for a human to recognize. We’re the first to quantify what this would mean. Our results show that not only is this not the case with today’s state of the art, but also that our current evaluation methods don’t have the ability to tell us when it is the case because standard datasets are so skewed toward easy images,” says Jesse Cummings, an MIT graduate scholar in electrical engineering and laptop science and co-first creator with Mayo on the paper.

From ObjectNet to MVT

A couple of years in the past, the crew behind this venture recognized a major problem within the area of machine studying: Models have been combating out-of-distribution pictures, or pictures that weren’t well-represented within the coaching knowledge. Enter ObjectNet, a dataset comprised of pictures collected from real-life settings. The dataset helped illuminate the efficiency hole between machine studying fashions and human recognition talents, by eliminating spurious correlations current in different benchmarks — for instance, between an object and its background. ObjectNet illuminated the hole between the efficiency of machine imaginative and prescient fashions on datasets and in real-world functions, encouraging use for a lot of researchers and builders — which subsequently improved mannequin efficiency.

Fast ahead to the current, and the crew has taken their analysis a step additional with MVT. Unlike conventional strategies that target absolute efficiency, this new method assesses how fashions carry out by contrasting their responses to the simplest and hardest pictures. The research additional explored how picture issue may very well be defined and examined for similarity to human visible processing. Using metrics like c-score, prediction depth, and adversarial robustness, the crew discovered that tougher pictures are processed otherwise by networks. “While there are observable trends, such as easier images being more prototypical, a comprehensive semantic explanation of image difficulty continues to elude the scientific community,” says Mayo.

In the realm of well being care, for instance, the pertinence of understanding visible complexity turns into much more pronounced. The skill of AI fashions to interpret medical pictures, akin to X-rays, is topic to the range and issue distribution of the pictures. The researchers advocate for a meticulous evaluation of issue distribution tailor-made for professionals, guaranteeing AI techniques are evaluated based mostly on knowledgeable requirements, somewhat than layperson interpretations.

Mayo and Cummings are presently taking a look at neurological underpinnings of visible recognition as nicely, probing into whether or not the mind displays differential exercise when processing simple versus difficult pictures. The research goals to unravel whether or not complicated pictures recruit further mind areas not sometimes related to visible processing, hopefully serving to demystify how our brains precisely and effectively decode the visible world.

Toward human-level efficiency

Looking forward, the researchers should not solely centered on exploring methods to boost AI’s predictive capabilities concerning picture issue. The crew is engaged on figuring out correlations with viewing-time issue as a way to generate tougher or simpler variations of pictures.

Despite the research’s vital strides, the researchers acknowledge limitations, significantly by way of the separation of object recognition from visible search duties. The present methodology does consider recognizing objects, leaving out the complexities launched by cluttered pictures.

“This comprehensive approach addresses the long-standing challenge of objectively assessing progress towards human-level performance in object recognition and opens new avenues for understanding and advancing the field,” says Mayo. “With the potential to adapt the Minimum Viewing Time difficulty metric for a variety of visual tasks, this work paves the way for more robust, human-like performance in object recognition, ensuring that models are truly put to the test and are ready for the complexities of real-world visual understanding.”

“This is a fascinating study of how human perception can be used to identify weaknesses in the ways AI vision models are typically benchmarked, which overestimate AI performance by concentrating on easy images,” says Alan L. Yuille, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Cognitive Science and Computer Science at Johns Hopkins University, who was not concerned within the paper. “This will help develop more realistic benchmarks leading not only to improvements to AI but also make fairer comparisons between AI and human perception.”

“It’s widely claimed that computer vision systems now outperform humans, and on some benchmark datasets, that’s true,” says Anthropic technical workers member Simon Kornblith PhD ’17, who was additionally not concerned on this work. “However, a lot of the difficulty in those benchmarks comes from the obscurity of what’s in the images; the average person just doesn’t know enough to classify different breeds of dogs. This work instead focuses on images that people can only get right if given enough time. These images are generally much harder for computer vision systems, but the best systems are only a bit worse than humans.”

Mayo, Cummings, and Xinyu Lin MEng ’22 wrote the paper alongside CSAIL Research Scientist Andrei Barbu, CSAIL Principal Research Scientist Boris Katz, and MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab Principal Researcher Dan Gutfreund. The researchers are associates of the MIT Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines.

The crew is presenting their work on the 2023 Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).