[ad_1]

In the summer season of 1998, the road to get into Mecca on a Sunday evening may stretch from the doorway to the Tunnel nightclub on Manhattan’s twelfth Avenue all the best way to the top of the block; tons of of our bodies, clothed and barely clothed in Versace and DKNY and Polo Sport, vibrating with anticipation. Passing vehicles with their booming stereos, both scoping out the scene or trying to find parking, provided a preview of what was inside: the sounds of Jay-Z and Busta Rhymes and Lil’ Kim. These individuals weren’t ready simply to pay attention to music. They have been there to be half of it. To be within the room the place Biggie Smalls and Mary J. Blige had carried out. To be on the dance flooring when Funkmaster Flex dropped a bomb on the subsequent summer season anthem. They have been ready to be on the middle of hip-hop.

What they didn’t understand was that the middle of hip-hop had shifted. Relocated not simply to a different membership or one other borough, however to a beachfront property in East Hampton. Although Sundays on the Tunnel would endure for a number of extra years, nothing in hip-hop, or American tradition, would ever be fairly the identical once more.

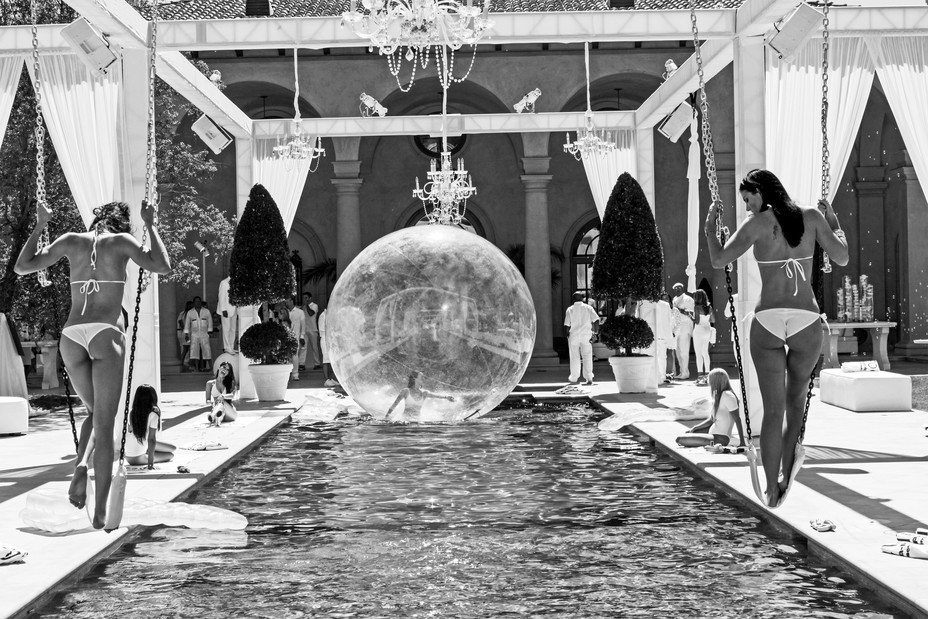

It’s been 25 years since Sean Combs, then referred to as Puff Daddy, hosted the primary of what would turn out to be his annual White Party at his house within the Hamptons. The home was all white and so was the gown code: not a cream frock or beige stripe to be seen. Against the cultural panorama of late-’90s America, the easy truth of a Black music government coming to the predominantly white Hamptons was offered as a spectacle. That summer season, The New York Times reported, “the Harlem-born rap producer and performer had played host at the Bridgehampton polo matches, looking dapper in a seersucker suit and straw boater. The polo-playing swells had invited him and he had agreed, as long as the day could be a benefit for Daddy’s House, a foundation he runs that supports inner-city children.”

To be clear, hip-hop was already a worldwide phenomenon whose booming gross sales have been achieved by means of crossover enchantment to white shoppers. Plenty of them have been out shopping for Dr. Dre and Nas CDs. Combs was well-known to hip-hop aficionados as an bold music mogul—his story of going from a Howard University dropout turned wunderkind intern at Uptown Records to a mega-successful A&R government there was the type of factor that made you marvel why you have been paying tuition. But to these younger white Americans, in 1998, he was simply the most recent rap sensation to ascend the pop charts. When Combs’s single “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down” hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 the 12 months earlier than, it was solely the tenth rap monitor to take action. The style was nonetheless seen as subversive—“Black music” or “urban music,” music that was made not for the polo-playing swells, however for the inner-city youngsters whom their charity matches benefited.

Hip-hop was born at a birthday celebration within the Bronx, a uncared for a part of a uncared for metropolis. The music and tradition that emerged have been formed by the distinctive mixture of Black and Puerto Rican individuals pushed, collectively, to the margins of society. It was our music. I used to be a Nuyorican woman in Brooklyn within the ’80s and ’90s; hip-hop soundtracked my life. If Casey Kasem was the voice of America, on my radio, Angie Martinez was the voice of New York.

When I went to school in Providence, I spotted all that I’d taken with no consideration. There was no Hot 97 to tune into. There have been no automotive stereos blasting something, a lot much less the most recent Mobb Deep. Hip-hop turned a care package deal or a telephone name to your greatest good friend from house: a solution to transcend time and area. It additionally turned a method for the few college students of shade to create group.

You might discover us, each Thursday, at Funk Night, dancing to Foxy Brown or Big Pun. Sundays, when the varsity’s alternative-rock station turned the airways over to what the trade termed “Black music” have been a day of revelry. Kids who got here again from a visit to New York with bootleg hip-hop mixtapes from Canal Street or off-the-radio recordings from Stretch Armstrong and Bobbito Garcia’s underground present have been lauded like pirates returning house with a bounty. We knew that hip-hop was many issues, however not static. We understood that it was going to evolve. What we weren’t maybe prepared for was for it to go really mainstream—to belong to everybody.

The media have been fast to anoint Combs a “modern-day Gatsby,” a moniker Combs himself appears to have relished. “Have I read The Great Gatsby?” he mentioned to a reporter in 2001. “I am the Great Gatsby.” It’s an apparent comparability—males of latest cash and sketchy pasts internet hosting their method into Long Island well mannered society—however a lazy one. Fitzgerald’s character used wealth to show that he might match into the old-money world. Combs’s White Party showcased his world; he invited his friends to step into his universe and play on his phrases. And, in doing so, he shifted the bigger tradition.

Would frat boys ever have rapped alongside to Kanye West with out the White Party? Would tech bros have purchased $1,000 bottles of $40 liquor and drunkenly belted out the lyrics to “Empire State of Mind”? Would Drake have headlined worldwide excursions? Would midwestern housewives be posting TikToks of themselves disinfecting counter tops to Cardi B songs? It’s onerous to think about {that a} single social gathering (that includes a Mister Softee truck) might redefine who will get to be a bona fide international pop star however, by all accounts, Puffy was no abnormal host.

The man had a imaginative and prescient. “I wanted to strip away everyone’s image,” Combs instructed Oprah Winfrey years after the primary White Party, “and put us all in the same color, and on the same level.” That the extent chosen was a playground for the white and rich was no accident. Upon closing a merger of his Bad Boy report label with BMG for a reported $40 million in 1998, he instructed Newsweek, “I’m trying to go where no young Black man has gone before.”

“It was about being a part of the movement that was a new lifestyle behind hip-hop,” Cheryl Fox instructed me. Now a photographer, she labored for Puffy’s publicist on the time of the primary White Party. The Hamptons, the all-white apparel: It was Puffy’s concept. But the white individuals, she mentioned, have been a publicity technique. “He was doing clubs, and he was doing parties that did not have white people,” she instructed me. “I brought the worlds together, and then I was like, ‘You got to step out of the music. You can’t just do everything music.’” She meant that he ought to broaden the visitor listing to incorporate actors and designers and financiers—the varieties of people that have been already flocking to the Hamptons.

In the top, “I had the craziest mix,” Combs instructed Oprah. “Some of my boys from Harlem; Leonardo DiCaprio, after he’d just finished Titanic. I had socialites there and relatives from down south.” Paris Hilton was there. Martha Stewart was there. “People wanted to be down with Puff,” Gwen Niles, a Bad Boy rep on the time, instructed me about that first social gathering. “People were curious: Who is this rap guy?”

Hip-hop was already widespread. The message the social gathering despatched was that hip-hop, and the individuals who made it, have been additionally “safe.”

Rap music was for therefore lengthy solid by white media as harmful, the sonic embodiment of lawlessness and violence. This narrative was so sticky that it saved hip-hop confined to the margins of popular culture regardless of its business success.

Hip-hop didn’t at all times assist itself out right here. Artists screwed up within the methods artists in all genres do—with drug addictions, outbursts, arrests—however when it got here to hip-hop, these transgressions have been used to strengthen cultural stereotypes. Misogyny had been embedded within the lyrics of hip-hop practically since its inception. A heartbreaking 2005 function by Elizabeth Méndez Berry in Vibe uncovered the real-world violence inflicted upon girls by a few of hip-hop’s most beloved artists, together with Biggie Smalls and Big Pun. Homophobia in hip-hop perpetuated anti-queer attitudes, significantly in communities of shade. And though lyrical battles have at all times been a factor, rhetorical fights by no means wanted to turn out to be lethal bodily ones.

This was the context wherein Puffy headed to the Hamptons. Though solely 28, he had baggage. While a younger government at Uptown in 1991, he had organized a star basketball recreation at CUNY’s City College to boost cash for AIDS charities. Tickets have been oversold, and a stampede left 9 individuals lifeless and plenty of extra injured. The tragedy stayed within the headlines for weeks. (Years later, Puffy would settle civil fits with victims.)

In 1993, Combs launched Bad Boy Records, with a roster of stars reminiscent of Biggie. The label met with quick success, but additionally controversy, after a taking pictures involving the California rapper Tupac Shakur embroiled Bad Boy in a contentious battle between East and West. By the spring of 1997, Biggie and Tupac have been lifeless—Biggie gunned down in Los Angeles in what seemed to be retribution for the killing of Tupac the 12 months earlier than. Biggie was shot whereas stopped at a pink mild; Combs was in one other automotive within the entourage. (Neither homicide has been solved.) That fall, Combs carried out “I’ll Be Missing You,” his tribute to Biggie, reside at MTV’s Video Music Awards. With a choir within the rafters, Combs danced by means of his grief. It was a second of rebirth, of reinvention. Combs and the gospel singers wore white.

To be clear, most of what Puffy was making as an artist and producer on this period was accessible to a white, prosperous fan base. These have been the type of tracks that sampled songs your dad and mom would have danced to, spliced and sped up so that you just needed to bounce to them now. Outside of “I’ll Be Missing You” and some songs about heartbreak, lots of the lyrics have been about getting, having, and spending cash.

But Puffy made attainable the crossover explosion of extra substantial artists reminiscent of Lauryn Hill and OutKast and Jay-Z, the primary era of hip-hop superstars.

You might additionally say that Puffy took a musical neighborhood—one which held historical past and heritage and layers of which means—and gentrified it. Cleaned it up for whiter, wealthier patrons to take pleasure in, individuals who had no concept of what the “old ’hood” was about. Both issues could be true.

The summer season of 1998 was additionally the summer season earlier than my final 12 months of faculty. Up in Providence, a neighborhood copycat to Hot 97 had cropped up and gained traction: WWKX, Hot 106, “the Rhythm of Southern New England.” Seemingly in a single day, the frat homes added DMX to their rotation. A classmate—a white socialite from the Upper East Side—got here again senior 12 months with field braids describing herself as an actual “hip-hop head.” Funk Night turned a campus-wide phenomenon, after which it ceased to exist. Nobody wanted a hip-hop evening when each evening was hip-hop evening.

In rap, the sensation was “I’m keeping it real. I’m gonna stay on this block,” Jay-Z recounts of this period within the Bad Boy documentary, Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop. “And our feeling was like, Yeah? I’ll see you when I get back.” Emotions round this ran scorching on the time—the concept hip-hop had left its true followers behind. But ultimately, extra of us have been joyful to see hip-hop conquer the world than have been grouching within the nook in regards to the good ol’ days.

In 2009, Puffy, by then referred to as Diddy, relocated his White Party to Los Angeles; hip-hop’s new mecca was the land of superstar. The vibe, in keeping with individuals who have been there, simply wasn’t the identical. But hip-hop itself was transferring on to greater and greater arenas. In 2018, hip-hop dominated streaming, and accounted for greater than 24 % of report gross sales that 12 months. That identical 12 months, Eminem headlined Coachella, Drake dominated the Billboard 100 for months, and Kendrick Lamar received a Pulitzer Prize.

Then one thing shifted once more. This 12 months isn’t simply the twenty fifth anniversary of the primary White Party. It’s the fiftieth anniversary of hip-hop itself. And though it’s come a good distance since Kool Herc deejayed a Bronx basement dance social gathering, the style seems to be struggling a midlife stoop.

For the first time in three a long time, no hip-hop single has hit No. 1 but this 12 months. Record gross sales are down. According to at least one senior music government I spoke with, who requested to stay nameless as a result of she wasn’t licensed to talk, festivals have been reluctant to e-book rappers as headliners since 2021. That’s the 12 months that eight individuals have been crushed to demise on the Astroworld Festival in Houston; two extra died later of their accidents. The performer Travis Scott was accused (pretty or unfairly) of riling up the group. (Coachella hasn’t had a real hip-hop headliner since Eminem.)

But the opposite query is: Which headliners would they even e-book? Kendrick Lamar is winding down his 2022 tour. Nicki Minaj doesn’t have a brand new album popping out till the autumn. Staple acts reminiscent of J. Cole most likely received’t launch an album this 12 months in any respect. Megan Thee Stallion, who obtained shot a number of years in the past and has been feeling burned out by the trade, is taking a break from music. As the legendary artists Too $hort and E-40 wrote on this journal, since 2018, hip-hop has seen not less than one rapper’s life a 12 months ended by violence. The careers of Gunna and Young Thug—two main acts on the rise—have stalled whereas they’ve been caught up in RICO costs in Atlanta. (Perhaps sensing a chance, Drake simply introduced {that a} new album and tour could be coming quickly.)

Recently, The New York Times ran an article about how the Hamptons have misplaced their cool. Too prosperous. Too outdated. Too out of contact. Maybe hip-hop, for the primary time, is affected by comparable doldrums. But obituaries to the style have been written earlier than. It’s solely a matter of time earlier than a brand new Gatsby exhibits up, able to throw a celebration.

[ad_2]