Imagine Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, draped in pristine white himations, walking into your local CrossFit box or SoulCycle class. Socrates, probably already asking the buff dude on the assault bike, “What is endurance, really?” Plato would be eyeing the perfect geometric forms of the kettlebells, and Aristotle would be taking notes on the ‘mean’ between lifting too little and tearing a rotator cuff.

It sounds like the setup to a bad joke, but if we look at modern fitness through the lens of these ancient philosophers, we might just discover that our Instagram-fueled pursuit of the perfect “summer body” is missing the point by about 2,400 years. They didn’t have pre-workout powder or fitness trackers, but they had some surprisingly sharp—and often hilarious—takes on why you should put down the phone and pick up a weight.

The Socratic Shame-Session: “No Man Has the Right to Be an Amateur”

Let’s start with Socrates, the original philosophical troll who loved nothing more than exposing people’s ignorance. If he saw you skipping leg day, he wouldn’t just judge you silently. Oh no. He’d corner you by the smoothie bar and deliver a verbal smackdown.

Socrates famously declared, “No man has the right to be an amateur in the matter of physical training. It is a shame for a man to grow old without seeing the beauty and strength of which his body is capable”. To him, neglecting your body wasn’t just a personal choice; it was a moral failing, a disgrace.

He’d look at our culture of convenience—door-dash, desk jobs, binging entire seasons in a weekend—and weep. In a dialogue recorded by his student Xenophon, Socrates chastises a young man in poor shape by saying, “You look as if you need exercise, Epigenes.” When the young man protests, “Well, I’m not an athlete,” Socrates unleashes a torrent of reasons that still sting today. He argues that being out of shape means you’re more likely to die disgracefully in war, be taken prisoner, be thought a coward, and generally live a life of misery. His ultimate point? The pain of training is “far lighter and far pleasanter” than the consequences of being unfit.

Socrates saw the body as essential for everything—even thinking. He noted that “grave mistakes may often be traced to bad health” and that a sick body could lead to loss of memory, depression, and discontent. So, the next time you blame “brain fog” for a mistake at work, remember: Socrates would probably tell you to go for a run first.

Plato’s Wrestling Match: The Egghead Who Could Bench You

Now, meet Plato. We picture him as the ultimate ivory-tower intellectual, but history tells a different story. The man was a jock. His real name was Aristocles, but his wrestling coach nicknamed him “Plato,” meaning “broad,” on account of his impressively wide, muscular shoulders. He wasn’t just playing around; he was good enough to compete at the Isthmian Games, a major athletic festival akin to the Olympics.

This gives his philosophy serious street cred. Plato wasn’t some skinny theorist preaching about a body he didn’t understand. He lived it. In his blueprint for the perfect society, The Republic, he insisted on a holistic education that trained the mind and the body equally for all citizens. He believed in “a sound mind in a sound body,” a concept that would later be perfectly captured by the Latin phrase mens sana in corpore sano.

But here’s the funny part for today’s fitness extremists: Plato was all about balance and temperance. He warned against overdoing it, comparing obsessive physical training to overdosing on music and poetry. He believed the goal was to tune the body and mind like a lyre, “adjusting the tension of each to the right pitch”. His ideal was to be so healthy you’d rarely need a doctor.

He’d look at the modern “grindset” guru doing two-a-days until he pukes and say, “My dude, you have thrown the harmony of your soul into chaos. Please, take a nap and read a dialogue.”

Aristotle’s Goldilocks Gym: Seeking the “Golden Mean” of Fitness

Then there’s Aristotle, the philosopher of the “Golden Mean”—the virtuous sweet spot between two extremes. Cowardice is one extreme, recklessness is the other; courage is the virtuous mean in the middle. He applied this same logic directly to fitness.

Aristotle didn’t idolize the hulking, one-rep-max powerlifter or the skeletal marathon runner. His ideal athlete was the pentathlete—the person who competed in five different events: discus, javelin, long jump, sprint, and wrestling. Why? Because the pentathlete struck the perfect balance. They were strong, but not overspecialized; they had endurance, but not at the complete expense of power. They were, in his words, “naturally adapted for bodily exertion and for swiftness of foot” and thus the most beautiful.

He’d walk into a gym today and be horrified by the segregation. “Why is that man only moving in slow, short motions near the mirror?” he’d ask of the bodybuilder. “And why is that woman running to nowhere on a spinning belt for an hour, achieving no tangible goal?” He’d point you to the person doing a workout that includes lifting, sprinting, and gymnastics—the modern CrossFitter or functional fitness enthusiast—and say, “There! That person understands kalokagathia!”

Kalokagathia is a fantastic Greek mashup word combining kalos (beautiful) and agathos (good). It represents the ideal harmony between a virtuous inner character and a capable, excellent outer form. For Aristotle, true fitness wasn’t just aesthetic; it was about being functionally good and beautiful, inside and out.

The Hippocratic Hangover: Let Food Be Thy Meme

We can’t talk Greek health without mentioning Hippocrates, the “Father of Medicine.” While not a philosopher in the same vein, his influence is the bedrock of our wellness culture. He championed the holistic view that health was a balance between the individual and their environment.

He’d be utterly baffled by our “wellness” industry. “You mean to tell me,” he’d sputter, “that you extract this ‘green juice’ at great cost, ship it in plastic, and drink it cold, rather than simply eating seasonal vegetables? And you call this progress?”

His most famous quote, “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,” is now plastered on every overpriced juice cleanse bottle. He’d probably sue for misuse of his good name. For Hippocrates and his followers, health promotion was straightforward: physical activity, good nutrition (figs and olive oil for athletes!), and a balanced mind. They even used music and theater as therapy, believing healing the soul healed the body. Imagine being prescribed a front-row seat to a tragedy at the Theatre of Epidaurus instead of a pill.

The Modern Temple of Gainz

So, what would these ancient Greeks think of our fitness world today?

- Socrates would be on social media, not posting thirst traps, but asking every influencer: “What is ‘fit’? Define your terms! Is your six-pack a sign of virtue or just a sign you’re dehydrated?” He’d see our obsession with metrics (steps, heart rate, calories) as a distraction from the true purpose: knowing and fulfilling our physical potential.

- Plato would warn us that our specialized, often obsessive routines are creating souls out of tune. He’d advocate for more “simple and flexible” training that leaves us independent and resilient.

- Aristotle would give a thumbs-up to functional fitness trends but would urge us to seek balance in all things—workouts, diet, rest. He’d remind us that “excessive and insufficient exercise destroy one’s strength” and that the right amount “produces, increases and preserves it”.

- Hippocrates would shake his head at our miracle cures and complex diets, pointing instead to moderation, whole foods, and the healing power of community and art.

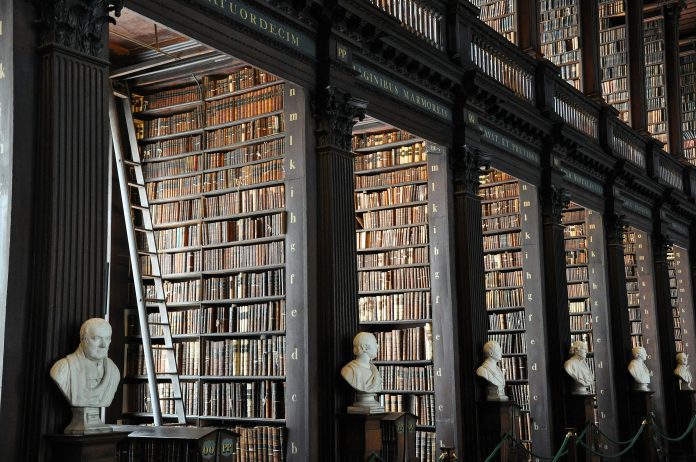

In the end, they’d all agree on one thing: the gym isn’t just a place to sculpt glutes for a photo. It’s a modern gymnasion—a training ground for the complete human being. It’s where we practice the ancient virtues of discipline (sophrosyne), excellence (arete), and the pursuit of human flourishing (eudaimonia).

So next time you lace up your trainers, remember: you’re not just going for a run. You’re on a philosophical odyssey, seeking your own personal kalokagathia. Just try not to pull a muscle while contemplating the meaning of it all.

by ERENE LAGOUROU