[ad_1]

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

In 1713, a cache of Roman cash was found in Transylvania, a number of of which bore the portrait and title of Sponsian—however there aren’t any historic information of a Roman emperor with that title. The cash largely have been dismissed as forgeries for greater than a century, however a re-analysis utilizing a wide range of physics-based strategies has yielded proof that they is perhaps genuine, in accordance with a current paper printed within the journal PLoS ONE. So Sponsian could have been an actual emperor in spite of everything.

One of the Sponsian cash is now within the Brukenthal National Museum in Sibiu, Romania; one other is a part of the Hunterian assortment on the University of Glasgow. “This has been a very thrilling undertaking for the Hunterian and we’re delighted that our findings have impressed collaborative analysis with museum colleagues in Romania,” mentioned co-author Jesper Ericsson, curator of numismatics on the Hunterian. “Not solely can we hope that this encourages additional debate about Sponsian as a historic determine, but additionally the investigation of cash referring to him held in different museums throughout Europe.”

Sponsian (or Sponsianus) appears to have been an obscure Roman army commander within the Roman province of Dacia, an remoted gold mining outpost that overlaps with modern-day Romania. Per the authors, he was almost definitely lively throughout a essential interval of unrest in the course of the third century CE. After the assassination of Emperor Severus Alexander—by his personal troops, no much less—the Roman Empire was besieged by barbarian invasions, peasant rebellions, civil wars, a pandemic (the Plague of Cyprian), and the rise of a number of usurpers vying for energy. Due to the ensuing forex debasement and financial collapse, by the 260s, there have been three competing states: the Gallic Empire, the Palmyrene Empire, and the Italy-centric Roman Empire caught between them. Things did not stabilize politically till Diocletian rose to energy and restructured the imperial authorities in 284.

Sponsian is so obscure that the cash bearing his title are the one concrete proof of his existence. At the time of their discovery, the cash have been deemed genuine. But doubts about their authenticity grew over time, and in 1868, French numismatist Henri Cohen declared the Sponsian cash to be “very poor high quality trendy forgeries”—probably the work of a Viennese forger who thought inventing an emperor would higher be a focus for collectors. So Sponsian, by extension, could by no means have existed. The cash have been heavier than typical, with inscriptions inconsistent with different Roman cash. Others have argued that there have been so many self-proclaimed rulers throughout that chaotic interval and their time in energy was so fleeting that the discrepancies should not be shocking.

P.N. Pearson et al., 2022/PLoS ONE

Co-author Paul Pearson of University College London spearheaded this newest undertaking—the primary time a Sponsian coin has been subjected to scientific evaluation. Pearson noticed images of the Hunterian coin whereas researching a e-book on the historical past of the Roman Empire in the course of the pandemic. He famous small scratches on the floor and thought this might be proof that the coin may need been in circulation since cash carried about in purses or pouches tended to get scratched.

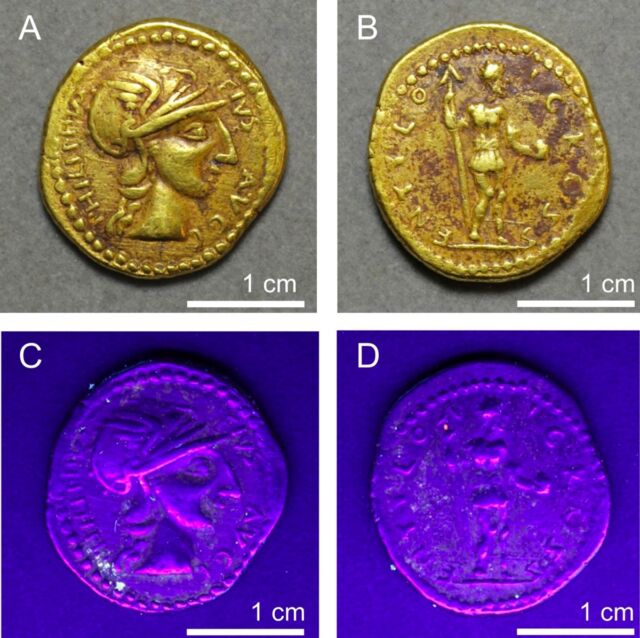

Pearson and his co-authors employed a spread of analytic strategies for 4 of the cash from that 18th-century cache within the Hunterian assortment, together with the Sponsian coin and cash inscribed with the names of Plautius, Philip the Arab, and Gordian III. (The cash as soon as belonged to 1 William Hunter, who seemingly acquired them from the property of a widely known Viennese antiquarian named Joseph de France.) Those strategies included traditional mild microscopy, ultraviolet imaging, scanning electron microscopy, and reflection mode Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. They did the identical for 2 different Roman cash whose authenticity had been confirmed for comparability functions.

The evaluation confirmed the presence of scratches and different indicators of damage and tear generally seen in real Roman cash. Further, the chemical evaluation indicated that every one 4 cash had been buried in soil for hundreds of years earlier than being uncovered to air. Based on the evaluation of Pearson et al., the Brukenthal National Museum has positioned a Sponsian coin on public show as a real artifact.

“I believe we have established with a very high degree of confidence that they are genuine,” Pearson instructed the Guardian, though he admitted that the query of Sponsian’s id was “more speculative.” However, the authors consider Sponsian could have assumed command as imperator (“supreme army commander) of Dacia when the inhabitants was reduce off from the remainder of the empire, surrounded by hostile enemies. Given their mining assets, Dacia might have minted their very own cash with Sponsian’s picture, which might have helped cement his authority and keep financial stability and social order till the realm was lastly evacuated between 271 and 275 CE.

The analysis has obtained blended responses from different consultants. Adrastos Omissi of the University of Glasgow instructed the Guardian that it was a “good piece of labor” and that he discovered the argument each for the existence of Sponsian and his function as a self-appointed ruler of Dacia fairly convincing, particularly since, on the time, “the bar for being an emperor was very low.” But Richard Abdy, curator of Roman and Iron Age coins at the British Museum, did not mince words about his skepticism. “They’ve gone full fantasy,” he instructed the Guardian. “It’s circular evidence. They’re saying because of the coin there’s the person, and the person therefore must have made the coin.”

DOI: PLoS ONE, 2022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0274285 (About DOIs).