[ad_1]

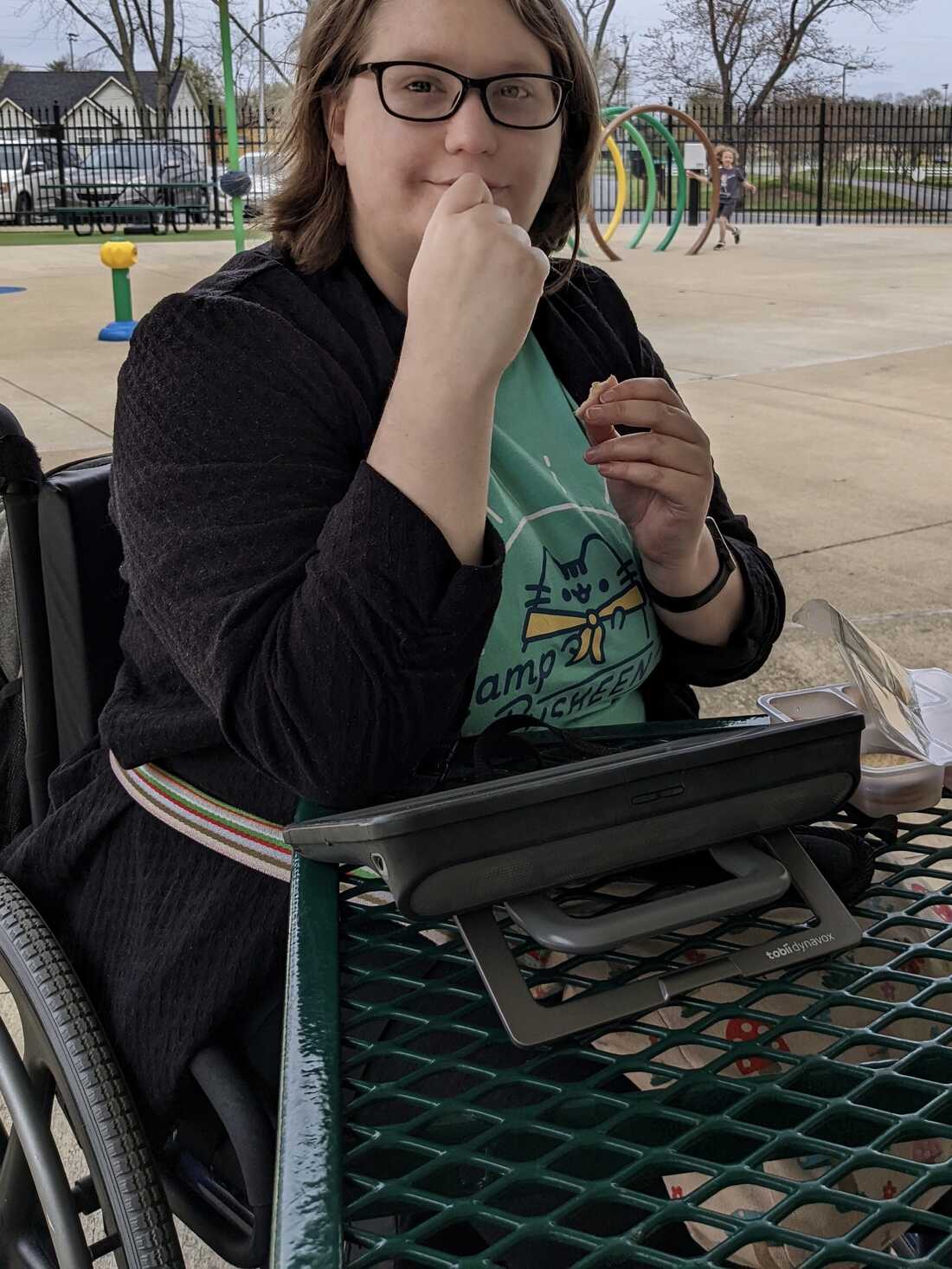

Courtney Johnson, who has autism and a number of continual sicknesses, lives comparatively independently. Her grandparents and buddies have helped her entry social providers. Still, she says, “serious about the longer term is a bit terrifying to me.”

Tristan Lane

conceal caption

toggle caption

Tristan Lane

Courtney Johnson, who has autism and a number of continual sicknesses, lives comparatively independently. Her grandparents and buddies have helped her entry social providers. Still, she says, “serious about the longer term is a bit terrifying to me.”

Tristan Lane

Thinking concerning the future makes Courtney Johnson nervous.

The 25-year-old blogger and faculty pupil has autism and several other continual sicknesses, and with the assist of her grandparents and buddies, who assist her entry a posh community of social providers, she lives comparatively independently in Johnson City, Tenn.

“If one thing occurs to them, I’m not sure what would occur to me, particularly as a result of I’ve issue with navigating issues that require extra purple tape,” she says.

Johnson says she hasn’t made plans that might guarantee she receives the identical stage of assist sooner or later. She particularly worries about being taken benefit of or being bodily harmed if her household and buddies can not help her — experiences she’s had up to now.

“I like with the ability to know what to anticipate, and serious about the longer term is a bit terrifying to me,” she says.

Johnson’s state of affairs is not distinctive.

25% of U.S. adults dwell with a incapacity

Experts say many individuals with mental and developmental disabilities don’t have long-term plans for when relations lose the flexibility to assist them get entry to authorities providers or to take care of them instantly.

Families, researchers, authorities officers, and advocates fear that the shortage of planning — mixed with a social security web that is filled with holes — has set the stage for a disaster wherein individuals with disabilities can not dwell independently of their communities. If that occurs, they might find yourself caught in nursing properties or state-run establishments.

“There’s simply potential for an amazing human toll on people if we do not resolve this downside,” says Peter Berns, CEO of the Arc of the United States, a nationwide disability-rights group.

About 25% of adults within the U.S. dwell with a incapacity, in accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly 75% of Americans with disabilities dwell with a household caregiver, and about 25% of these caregivers are 60 or older, in accordance with the Center on Developmental Disabilities on the University of Kansas.

Any care plan must be ‘a dwelling doc, as a result of issues change’

But solely about half of households that take care of a beloved one with disabilities have made plans for the longer term, and a good smaller portion have revisited these plans to make sure they’re updated, says Meghan Burke, an affiliate professor of particular training on the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign.

“Engaging in it as soon as is nice, proper? But you possibly can’t solely interact in it as soon as,” she says. “It’s a dwelling doc, as a result of issues change, individuals change, circumstances change.”

Burke’s analysis has discovered a number of obstacles to planning for the longer term: monetary constraints, reluctance to have arduous conversations, hassle understanding authorities providers. Creating plans for individuals with disabilities is also a posh course of, with many questions for households to reply: What are their kin’ well being wants? What actions do they get pleasure from? What are their needs? Where will they dwell?

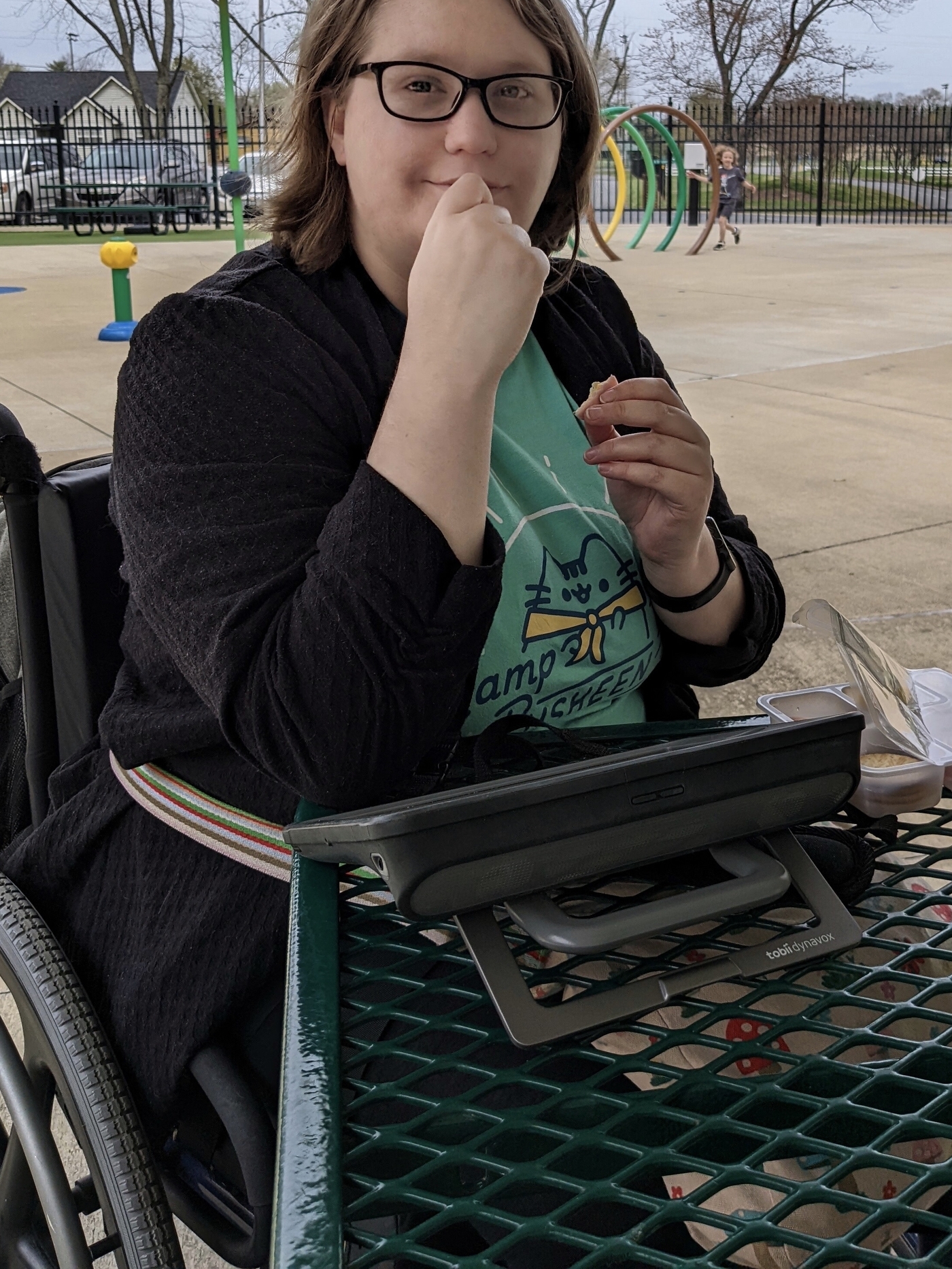

Rob Stone was born with a situation that restricts a lot of his motion. His mom, Jeneva, says her household has been “flummoxed” by the method of planning for the longer term. They simply need to ensure that Rob could have a say in the place he lives and the care he receives.

rahfoard

conceal caption

toggle caption

rahfoard

Rob Stone was born with a situation that restricts a lot of his motion. His mom, Jeneva, says her household has been “flummoxed” by the method of planning for the longer term. They simply need to ensure that Rob could have a say in the place he lives and the care he receives.

rahfoard

Burke has firsthand expertise answering these questions. Her youthful brother has Down syndrome, and he or she expects to develop into his main caregiver sooner or later — a state of affairs she stated is widespread and spreads the work of caregiving.

“This is an impending intergenerational disaster,” she stated. “It’s a disaster for the ageing mother and father, and it is a disaster for his or her grownup offspring with and with out disabilities.”

Nicole Jorwic, chief of advocacy and campaigns for Caring Across Generations, a nationwide caregiver advocacy group, says the community of state and federal packages for individuals with disabilities could be “extraordinarily sophisticated” and is filled with holes. She has witnessed these gaps as she has helped her brother, who has autism, get entry to providers.

“It’s actually troublesome for households to plan when there is not a system that they will depend on,” she says.

Advocates see a continual underinvestment in Medicaid incapacity providers

Medicaid pays for individuals to obtain providers in dwelling and group settings by packages that adjust state to state. But Jorwic says there are lengthy waitlists. Data collected and analyzed by KFF exhibits that queue is made up of a whole bunch of 1000’s of individuals throughout the nation. Even when individuals qualify, Jorwic provides, hiring somebody to assist could be troublesome due to persistent employees shortages.

Jorwic says extra federal cash may shorten these waitlists and enhance Medicaid reimbursements to well being care suppliers, which may assist with workforce recruitment. She blames continual underinvestment in Medicaid incapacity providers for the shortage of obtainable slots and a dearth of staff to assist individuals with disabilities.

“It’s going to be costly, however that is 4 many years of funding that ought to have been finished,” she says.

Congress just lately put about $12.7 billion towards enhancing state Medicaid packages for home- and community-based providers for individuals with disabilities, however that cash might be out there solely by March 2025. The Build Back Better Act, which died in Congress, would have added $150 billion, and funding was omitted of the Inflation Reduction Act, which grew to become legislation this summer season, to the disappointment of advocates.

Jeneva Stone’s household in Bethesda, Md., has been “flummoxed” by the long-term planning course of for her 25-year-old son, Rob. He wants advanced care as a result of he has dystonia 16, a uncommon muscle situation that makes shifting practically unattainable for him.

“No one will simply sit down and inform me what will occur to my son,” she says. “You know, what are his choices, actually?”

A particular financial savings account and plan in place for ‘supported decision-making’

Stone says her household has finished some planning, together with establishing a particular wants belief to assist handle Rob’s belongings and an ABLE account, a kind of financial savings account for individuals with disabilities. They’re additionally working to provide Rob’s brother medical and monetary energy of legal professional and to create a supported decision-making association for Rob to ensure he has the ultimate say in his care.

“We’re making an attempt to place that scaffolding in place, primarily to guard Rob’s means to make his personal selections,” she says.

Alison Barkoff is principal deputy administrator for the Administration for Community Living, a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Her company just lately launched what she known as a “first ever” nationwide plan, with a whole bunch of actions the private and non-private sectors can take to assist household caregivers.

“If we do not actually suppose and plan, I’m involved that we may have individuals ending up in establishments and different sorts of segregated settings that would and may have the ability to be supported in the neighborhood,” says Barkoff, who notes that these outcomes may violate the civil rights of individuals with disabilities.

She says her company is working to handle the shortages within the direct care workforce and within the provide of reasonably priced, accessible housing for individuals with disabilities, in addition to the shortage of disability-focused coaching amongst medical professionals.

Evan Woody has wanted round the clock care since his mind harm and lives along with his mother and father in Dunwoody, Ga. His father, Philip, says his household has some plans in place for Evan’s future, however one query continues to be unanswered: Where will Evan dwell when he can not dwell along with his mother and father?

Philip Woody

conceal caption

toggle caption

Philip Woody

Evan Woody has wanted round the clock care since his mind harm and lives along with his mother and father in Dunwoody, Ga. His father, Philip, says his household has some plans in place for Evan’s future, however one query continues to be unanswered: Where will Evan dwell when he can not dwell along with his mother and father?

Philip Woody

But ending up in a nursing dwelling or different establishment won’t be the worst end result for some individuals, says Berns, who factors out that individuals with disabilities are overrepresented in jails and prisons.

A step-by-step information to developing with the fitting plan

Berns’ group, the Arc provides a step-by-step planning information and has compiled a listing of native advocates, attorneys, and assist organizations to assist households. Berns says that ensuring individuals with disabilities have entry to providers — and the means to pay for them — is just one a part of a superb plan.

“It’s about social connections,” Berns says. “It’s about employment. It’s about the place you reside. It’s about your well being care and making selections in your life.”

Philip Woody feels as if he has ready fairly effectively for his son’s future. Evan, 23, lives along with his mother and father in Dunwoody, Ga., and wishes round the clock assist after a fall as an toddler resulted in a major mind harm. His mother and father present a lot of his care.

Woody says his household has been saving for years to supply for his son’s future, and Evan just lately acquired off a Medicaid waitlist and is getting assist to attend a day program for adults with disabilities. He additionally has an older sister in Tennessee who desires to be concerned in his care.

But two massive questions are plaguing Woody: Where will Evan dwell when he can not dwell at dwelling? And will that setting be one the place he can thrive?

“As a dad or mum, you’ll maintain your youngster in addition to you possibly can for so long as you possibly can,” Woody says. “But then no person after you go away will love them or take care of them the way in which that you just did.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nationwide, editorially impartial program of the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF).