[ad_1]

Image/Shutterstock.com

By Angharad Brewer Gillham, Frontiers science author

‘Social loafing’ is a phenomenon which occurs when members of a workforce begin to put much less effort in as a result of they know others will cowl for them. Scientists investigating whether or not this occurs in groups which mix work by robots and people discovered that people finishing up high quality assurance duties noticed fewer errors after they had been informed that robots had already checked a chunk, suggesting they relied on the robots and paid much less consideration to the work.

Now that enhancements in expertise imply that some robots work alongside people, there’s proof that these people have discovered to see them as team-mates — and teamwork can have detrimental in addition to optimistic results on individuals’s efficiency. People generally chill out, letting their colleagues do the work as a substitute. This is known as ‘social loafing’, and it’s widespread the place individuals know their contribution gained’t be observed or they’ve acclimatized to a different workforce member’s excessive efficiency. Scientists on the Technical University of Berlin investigated whether or not people social loaf after they work with robots.

“Teamwork is a mixed blessing,” mentioned Dietlind Helene Cymek, first writer of the examine in Frontiers in Robotics and AI. “Working together can motivate people to perform well but it can also lead to a loss of motivation because the individual contribution is not as visible. We were interested in whether we could also find such motivational effects when the team partner is a robot.”

A serving to hand

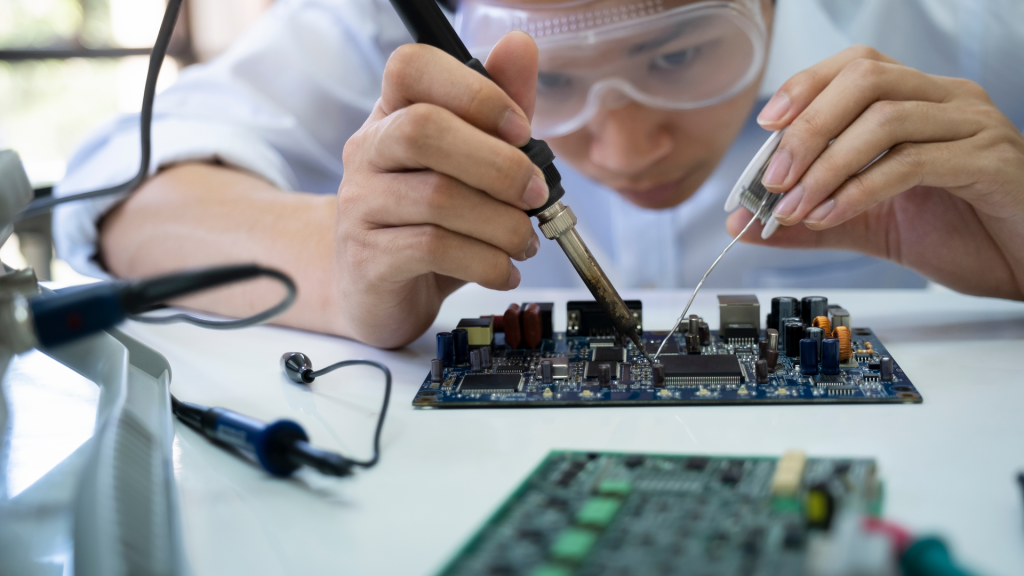

The scientists examined their speculation utilizing a simulated industrial defect-inspection job: circuit boards for errors. The scientists supplied photographs of circuit boards to 42 contributors. The circuit boards had been blurred, and the sharpened photographs might solely be seen by holding a mouse software over them. This allowed the scientists to trace contributors’ inspection of the board.

Half of the contributors had been informed that they had been engaged on circuit boards that had been inspected by a robotic known as Panda. Although these contributors didn’t work straight with Panda, that they had seen the robotic and will hear it whereas they labored. After inspecting the boards for errors and marking them, all contributors had been requested to charge their very own effort, how chargeable for the duty they felt, and the way they carried out.

Looking however not seeing

At first sight, it regarded as if the presence of Panda had made no distinction — there was no statistically vital distinction between the teams when it comes to time spent inspecting the circuit boards and the world searched. Participants in each teams rated their emotions of duty for the duty, effort expended, and efficiency equally.

But when the scientists regarded extra intently at contributors’ error charges, they realized that the contributors working with Panda had been catching fewer defects later within the job, after they’d already seen that Panda had efficiently flagged many errors. This might replicate a ‘looking but not seeing’ impact, the place individuals get used to counting on one thing and have interaction with it much less mentally. Although the contributors thought they had been paying an equal quantity of consideration, subconsciously they assumed that Panda hadn’t missed any defects.

“It is easy to track where a person is looking, but much harder to tell whether that visual information is being sufficiently processed at a mental level,” mentioned Dr Linda Onnasch, senior writer of the examine.

The experimental set-up with the human-robot workforce. Image equipped by the authors.

Safety in danger?

The authors warned that this might have security implications. “In our experiment, the subjects worked on the task for about 90 minutes, and we already found that fewer quality errors were detected when they worked in a team,” mentioned Onnasch. “In longer shifts, when tasks are routine and the working environment offers little performance monitoring and feedback, the loss of motivation tends to be much greater. In manufacturing in general, but especially in safety-related areas where double checking is common, this can have a negative impact on work outcomes.”

The scientists identified that their check has some limitations. While contributors had been informed they had been in a workforce with the robotic and proven its work, they didn’t work straight with Panda. Additionally, social loafing is difficult to simulate within the laboratory as a result of contributors know they’re being watched.

“The main limitation is the laboratory setting,” Cymek defined. “To find out how big the problem of loss of motivation is in human-robot interaction, we need to go into the field and test our assumptions in real work environments, with skilled workers who routinely do their work in teams with robots.”

Frontiers Journals & Blog