[ad_1]

In 1979 the Macintosh private pc existed solely because the pet thought of Jef Raskin, a veteran of the Apple II workforce, who had proposed that Apple Computer Inc. make a low-cost “appliance”-type pc that may be as straightforward to make use of as a toaster. Mr. Raskin believed the pc he envisioned, which he referred to as Macintosh, may promote for US $1000 if it was manufactured in excessive quantity and used a robust microprocessor executing tightly written software program.

Mr. Raskin’s proposal didn’t impress anybody at Apple Computer sufficient to convey a lot cash from the board of administrators or a lot respect from Apple engineers. The firm had extra urgent considerations on the time: the key Lisa workstation undertaking was getting beneath manner, and there have been issues with the reliability of the Apple III, the revamped model of the extremely profitable Apple II.

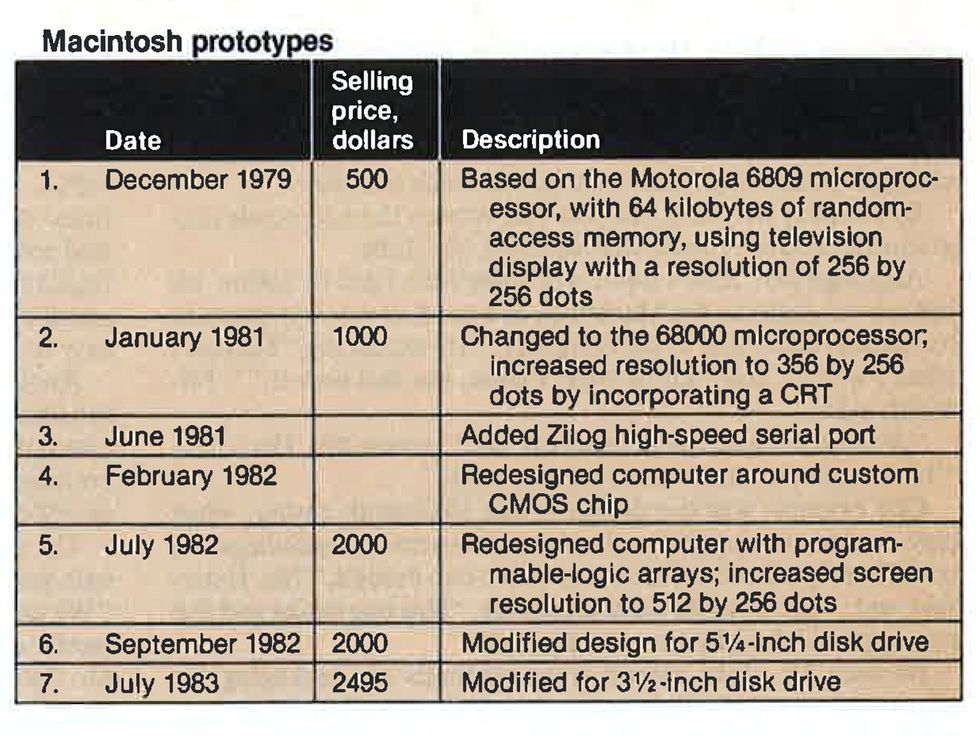

Although the percentages appeared towards it in 1979, the Macintosh, designed by a handful of inexperienced engineers and programmers, is now acknowledged as a technical milestone in private computing. Essentially a slimmed-down model of the Lisa workstation with lots of its software program options, the Macintosh bought for $2495 at its introduction in early 1984; the Lisa initially bought for $10,000. Despite criticism of the Macintosh—that it lacks networking capabilities ample for enterprise purposes and is awkward to make use of for some duties—the pc is taken into account by Apple to be its most vital weapon within the battle with IBM for survival within the personal-computer enterprise.

From the start, the Macintosh undertaking was powered by the devoted drive of two key gamers on the undertaking workforce. For Burrell Smith, who designed the Macintosh digital {hardware}, the undertaking represented a chance for a relative unknown to reveal excellent technical skills. For Steven Jobs, the 29-year-old chairman of Apple and the Macintosh undertaking’s director, it provided an opportunity to show himself within the company world after a short lived setback: though he cofounded Apple Computer, the corporate had declined to let him handle the Lisa undertaking. Mr. Jobs contributed comparatively little to the technical design of the Macintosh, however he had a transparent imaginative and prescient of the product from the start. He challenged the undertaking workforce to design one of the best product attainable and inspired the workforce by shielding them from bureaucratic pressures throughout the firm.

Burrell Smith and the Early Mac Design

Mr. Smith, who was a repairman within the Apple II upkeep division in 1979, had grow to be hooked on microprocessors a number of years earlier throughout a go to to the electronics-industry space south of San Francisco often known as Silicon Valley. He dropped out of liberal-arts research on the Junior College of Albany, New York, to pursue the chances of microprocessors—there isn’t something you may’t do with these issues, he thought. Mr. Smith later turned a repairman in Cupertino, Calif., the place he spent a lot time learning the cryptic logic circuitry of the Apple II, designed by firm cofounder Steven Wozniak.

Mr. Smith’s dexterity within the store impressed Bill Atkinson, one of many Lisa designers, who launched him to Mr. Raskin as “the man who’s going to design your Macintosh.” Mr. Raskin replied noncommittally, “We’ll see about that.”

However, Mr. Smith managed to study sufficient about Mr. Raskin ‘s conception of the Macintosh to whip up a makeshift prototype using a Motorola 6809 microprocessor, a television monitor, and an Apple II. He showed it to Mr. Raskin, who was impressed enough to make him the second member of the Macintosh team.

But the fledgling Macintosh project was in trouble. The Apple board of directors wanted to cancel the project in September 1980 to concentrate on more important projects, but Mr. Raskin was able to win a three-month reprieve.

Meanwhile Steve Jobs, then vice president of Apple, was having trouble with his own credibility within the company. Though he had sought to manage the Lisa computer project, the other Apple executives saw him as too inexperienced and eccentric to entrust him with such a major undertaking, and he had no formal business education. After this rejection, “he didn’t like the dearth of management he had,” famous one Apple government. “He was looking for his niche.”

Mr. Jobs took an interest within the Macintosh undertaking, and, presumably as a result of few within the firm thought the undertaking had a future, Mr. Jobs was made its supervisor. Under his path, the design workforce turned as compact and environment friendly because the Macintosh was tobe—a gaggle of engineers working at a distance from all of the conferences and paper-pushing of the company mainstream. Mr. Jobs, in recruiting the opposite members of the Macintosh workforce, lured some from different firms with guarantees of doubtless profitable inventory choices.

The Macintosh undertaking “was known in the company as ‘Steve’s folly.’”

With Mr. Jobs on the helm, the undertaking gained some credibility among the many board of administrators—however not a lot. According to at least one workforce member, it was identified within the firm as “Steve’s folly.” But Mr. Jobs lobbied for a much bigger price range for the undertaking and received it. The Macintosh workforce grew to twenty by early 1981.

The choice on what kind the Macintosh would take was left largely to the design group. At first the members had solely the fundamental ideas set forth by Mr. Raskin and Mr. Jobs to information them, in addition to the instance set by the Lisa undertaking. The new machine was to be straightforward to make use of and cheap to fabricate. Mr. Jobs needed to commit sufficient cash to construct an automatic manufacturing facility that may produce about 300 000 computer systems a yr. So one key problem for the design group was to make use of cheap components and to maintain the components depend low.

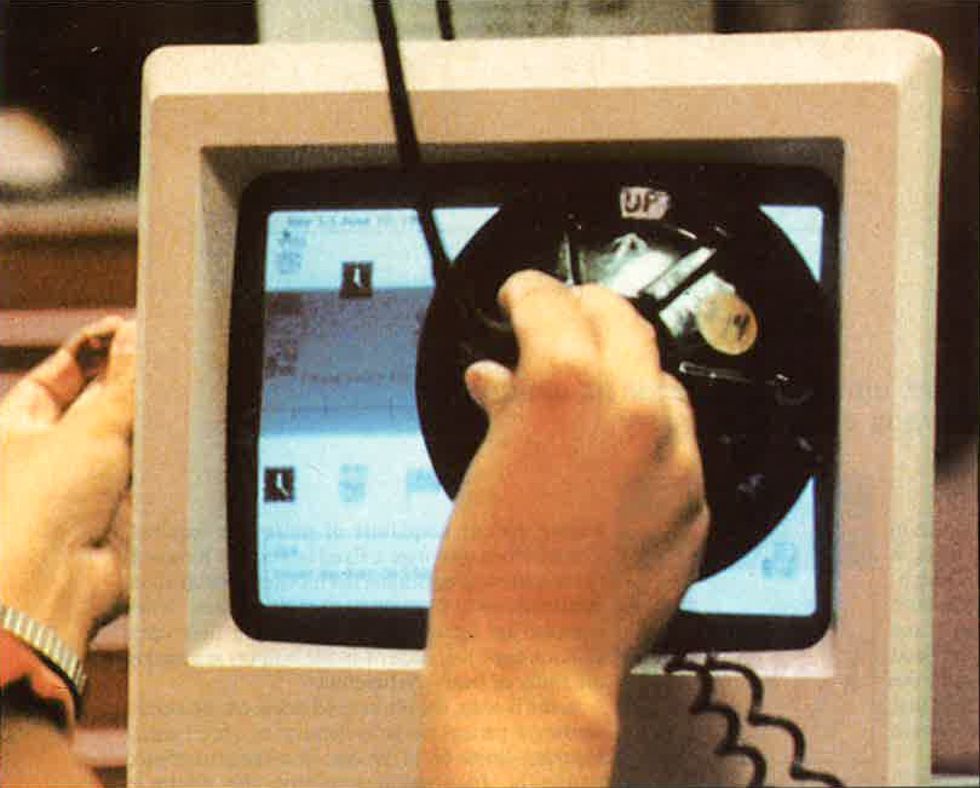

Making the pc straightforward to make use of required appreciable software program for the user-computer interface. The mannequin was, in fact, the Lisa workstation with its graphic “windows” to show concurrently many various applications. “Icons,” or little footage, have been used as an alternative of cryptic pc phrases to symbolize a collection of applications on the display screen; by transferring a “mouse,’’ a box the size of a pack of cigarettes, the user manipulated a cursor on the screen. The Macintosh team redesigned the software of the Lisa from scratch to make it operate more efficiently, since the Macintosh was to have far less memory than the 1 million bytes of the Lisa. But the Macintosh software was also required to operate quicker than the Lisa software, which had been criticized for being slow.

Defining the Mac as the Project Progressed

The lack of a precise definition for the Macintosh project was not a problem. Many of the designers preferred to define the computer as they went along. “Steve allowed us to crystallize the problem and the solution simultaneously,” recalled Mr. Smith. The methodology put pressure on the design workforce, since they have been frequently evaluating design alternate options. “We were swamped in detail,” Mr. Smith mentioned. But this fashion of working additionally led to a greater product, the designers mentioned, as a result of that they had the liberty to grab alternatives through the design stage to boost the product.

Such freedom wouldn’t have been attainable had the Macintosh undertaking been structured within the standard manner at Apple, in line with a number of of the designers. “No one tried to control us,” mentioned one. “Some managers like to take control, and though that may be good for mundane engineers, it isn’t good if you are self-motivated.”

Central to the success of this methodology was the small, intently knit nature of the design group, with every member being chargeable for a comparatively massive portion of the entire design and free to seek the advice of different members of the workforce when contemplating alternate options. For instance, Mr. Smith, who was effectively acquainted with the value of digital parts from his early work on decreasing the price of the Apple II, made many selections concerning the economics of Macintosh {hardware} with out time-consuming consultations with buying brokers. Because communication amongst workforce members was good, the designers shared their areas of experience by advising one another within the working phases, fairly than ready for a closing analysis from a gaggle of producing engineers. Housing all members of the design workforce in a single small workplace made speaking simpler. For instance, it was easy for Mr. Smith to seek the advice of a buying agent concerning the worth of components if he wanted to, as a result of the buying agent labored in the identical constructing.

Andy Hertzfeld, who transferred from the Apple II software program group to design the Macintosh working software program, famous, “In lots of other projects at Apple, people argue about ideas. But sometimes bright people think a little differently. Somebody like Burrell Smith would design a computer on paper and people would say. ‘It’ll never work.’ So instead Burell builds it lightning fast and has it working before the guy can say anything.”

“When you have one person designing the whole computer, he knows that a little leftover gate in one part may be used in another part.”

—Andy Herzfeld

The closeness of the Macintosh group enabled it to make design tradeoffs that may not have been attainable in a big group, the workforce members contended. The interaction between {hardware} and software program was essential to the success of the Macintosh design, utilizing a restricted reminiscence and few digital components to carry out complicated operations. Mr. Smith, who was in command of the pc’s complete digital {hardware} design, and Mr. Herzfeld turned shut buddies and sometimes collaborated. “When you have one person designing the whole computer,” Mr. Hertzfeld noticed, “he knows that a little leftover gate in one part may be used in another part.”

To promote interplay among the many designers, one of many first issues that Mr. Jobs did in taking up the Macintosh undertaking was to rearrange particular workplace house for the workforce. In distinction to Apple’s company headquarters, recognized by the corporate brand on an indication on its well-trimmed garden, the workforce’s new quarters, behind a Texaco service station, had no signal to establish them and no itemizing within the firm phone listing. The workplace, dubbed Texaco Towers, was an upstairs, low-rent, plasterboard-walled, “tacky-carpeted” place, “the kind you’d find at a small law outfit,’’ according to Chris Espinosa, a veteran of the original Apple design team and an early Macintosh draftee. It resembled a house more than an office, having a communal area much like a living room, with smaller rooms off to the side for more privacy in working or talking. The decor was part college dormitory, part electronics repair shop: art posters, beanbag chairs, coffee machines, stereo systems, and electronic equipment of all sorts scattered about.

“Whenever a competitor came out with a product, we would buy and dismantle it, and it would kick around the office.”

—Chris Espinosa

There have been no set work hours and initially not even a schedule for the event of the Macintosh. Each week, if Mr. Jobs was on the town (usually he was not), he would maintain a gathering at which the workforce members would report what that they had executed the earlier week. One of the designers’ sidelines was to dissect the merchandise of their opponents. “Whenever a competitor came out with a product, we would buy and dismantle it, and it would kick around the office,” recalled Mr. Espinosa.

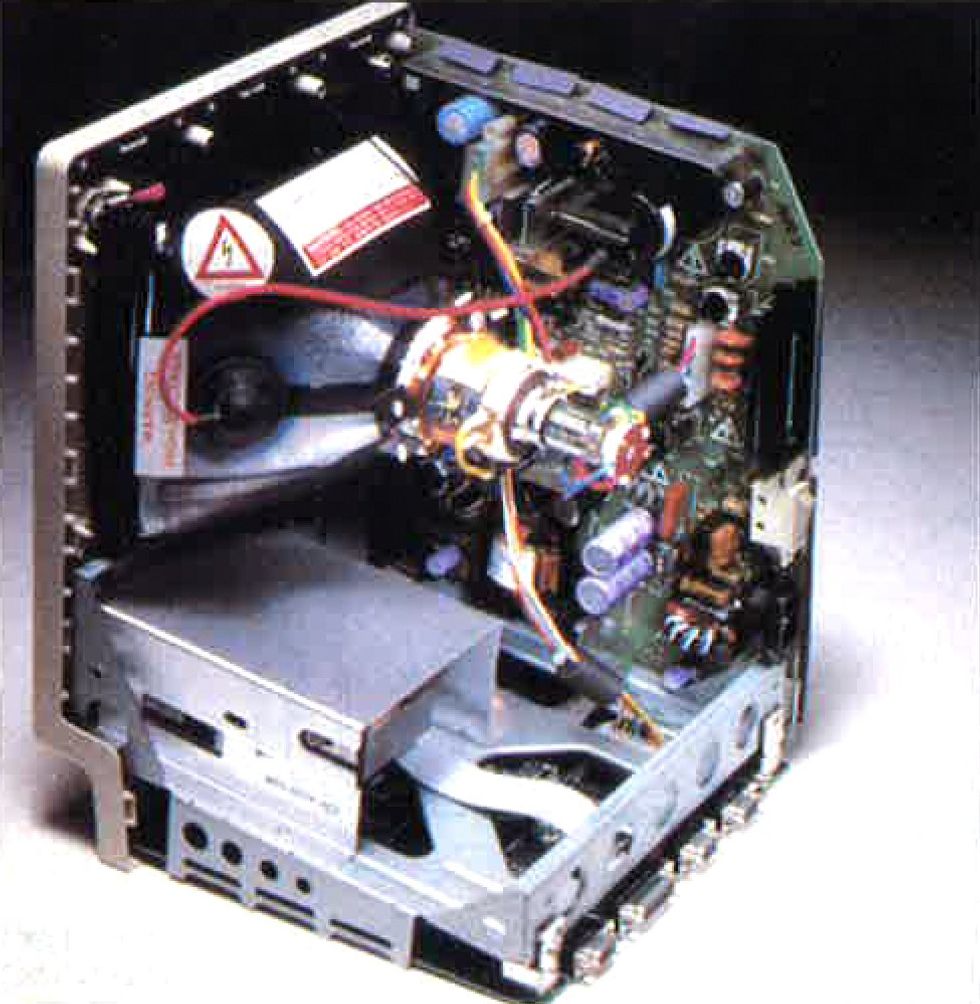

In this fashion, they realized what they didn’t need their product to be. In their opponents’ merchandise, Mr. Smith noticed a propensity for utilizing connectors and slots for inserting printed-circuit boards—a slot for the video circuitry, a slot for the keyboard circuitry, a slot for the disk drives, and reminiscence slots. Behind every slot have been buffers to permit alerts to go onto and off the printed-circuit board correctly. The buffers meant delays within the computer systems’ operations, since a number of boards shared a backplane, and the large capacitance required for a number of PC boards slowed the backplane. The variety of components required made the opponents’ computer systems onerous to fabricate, pricey, and fewer dependable. The Macintosh workforce resolved that their PC would have however two printed-circuit boards and no slots, buffers, or backplane.

A problem in constructing the Macintosh was to supply refined software program utilizing the fewest and least-expensive components.

To squeeze the wanted parts onto the board, Mr. Smith deliberate the Macintosh to carry out particular capabilities fairly than function as a versatile pc that may very well be tailor-made by programmers for all kinds of purposes. By rigidly defining the configuration of the Macintosh and the capabilities it will carry out, he eradicated a lot circuitry. Instead of offering slots into which the consumer may insert printed-circuit boards with such {hardware} as reminiscence or coprocessors, the designers determined to include lots of the fundamental capabilities of the pc in read-only reminiscence, which is extra dependable. The pc could be expanded not by slots, however by way of a high-speed serial port.

Writing the Mac’s Software

The software program designers have been confronted to start with with often-unrealistic schedules. “We looked for any place where we could beg, borrow, or steal code,” Mr. Herzfeld recalled. The apparent place for them to look was the Lisa workstation. The Macintosh workforce needed to borrow a number of the Lisa’s software program for drawing graphics on the bit-mapped show. In 1981, Bill Atkinson was refining the Lisa graphics software program, referred to as Quickdraw, and started to work part-time implementing it for the Macintosh.

Quickdraw was a scheme for manipulating bit maps to allow purposes programmers to assemble photos simply on the Macintosh bit-mapped show. The Quickdraw program permits the programmer to outline and manipulate a area—a software program illustration of an arbitrarily formed space of the display screen. One such area is an oblong window with rounded comers, used all through the Macintosh software program. Quickdraw additionally permits the programmer to maintain photos inside outlined boundaries, which make the home windows within the Macintosh software program seem to carry knowledge. The programmer can unite two areas, subtract one from the opposite, or intersect them.

In Macintosh, the Quickdraw program was to be tightly written in assembly-level code and etched completely in ROM. It would function a basis for higher-level software program to utilize graphics.

Quickdraw was “an amazing graphics package,” Mr. Hertzfeld famous, however it will have strained the capabilities of the 6809 microprocessor, the center of the early Macintosh prototype. Motorola Corp. introduced in late 1980 that the 68000 microprocessor was accessible, however that chip was new and unproven within the area, and at $200 apiece it was additionally costly. Reasoning that the value of the chip would come down earlier than Apple was prepared to start out mass-producing the Macintosh, the Macintosh designers determined to gamble on the Motorola chip.

Another early design query for the Macintosh was whether or not to make use of the Lisa working system. Since the Lisa was nonetheless within the early phases of design, appreciable improvement would have been required to tailor its working system for the Macintosh. Even if the Lisa had been accomplished, rewriting its software program in meeting code would have been required for the far smaller reminiscence of the Macintosh. In addition, the Lisa was to have a multitasking working system, utilizing complicated circuitry and software program to run multiple pc program on the identical time, which might have been too costly for the Macintosh. Thus the choice was made to write down a Macintosh working system from scratch, working from the fundamental ideas of the Lisa. Simplifying the Macintosh working system posed the fragile drawback of proscribing the pc’s reminiscence capability sufficient to maintain it cheap however not a lot as to make it rigid.

The Macintosh would don’t have any multitasking functionality however would execute just one purposes program at a time. Generally, a multitasking working system tracks the progress of every of the applications it’s working after which shops the complete state of every program—the values of its variables, the situation of this system counter, and so forth. This complicated operation requires extra reminiscence and {hardware} than the Macintosh designers may afford. However, the phantasm of multitasking was created by small applications constructed into the Macintosh system software program. Since these small applications—similar to one which creates the pictures of a calculator on the display screen and does easy arithmetic—function in areas of reminiscence separate from purposes, they will run concurrently with purposes applications.

Embedding Macintosh software program in 64 kilobytes of read-only reminiscence elevated the reliability of the pc and simplified the {hardware} [A]. About one third of the ROM software program is the working system. One third is taken up by Quickdraw, a program for representing shapes and pictures for the bit-mapped show. The remaining third is dedicated to the consumer interface toolbox, which handles the show of home windows, textual content modifying, menus, and the like. The consumer interface of the Macintosh consists of pull-down menus, which seem solely when the cursor is positioned over the menu identify and a button on the mouse is pressed. Above, a consumer analyzing the ‘file’ menu selects the open command, which causes the pc to load the file (indicated by darkened icon) from disk into inner reminiscence. The Macintosh software program was designed to make the toolbox routines optionally available for programmers; the purposes program presents the selection of whether or not or to not deal with an occasion [B].

Since the Macintosh used a memory-mapped scheme, the 68000 microprocessor required no reminiscence administration, simplifying each the {hardware} and the software program. For instance, the 68000 has two modes of operation: a consumer mode, which is restricted so {that a} programmer can’t inadvertently upset the memory-management scheme; and a supervisor mode, which permits unrestricted entry to the entire 68000’s instructions. Each mode makes use of its personal stack of tips to blocks of reminiscence. The 68000 was rigged to run solely within the supervisor mode, eliminating the necessity for the extra stack. Although seven ranges of interrupts have been accessible for the 68000, solely three have been used.

Another simplification was made within the Macintosh’s file construction, exploiting the small disk house with just one or two floppy disk drives. In the Lisa and most different working programs, two indexes entry a program on floppy disk, utilizing up treasured random-access reminiscence and rising the delay in fetching applications from a disk. The designers determined to make use of just one index for the Macintosh—a block map, positioned in RAM, to point the situation of a program on a disk. Each block map represented one quantity of disk house.

This scheme bumped into sudden difficulties and could also be modified in future variations of the Macintosh, Mr. Hertzfeld mentioned. Initially, the Macintosh was not supposed for enterprise customers, however because the design progressed and it turned obvious that the Macintosh would value greater than anticipated, Apple shifted its advertising plan to focus on enterprise customers. Many of them add onerous disk drives to the Macintosh, making the block-map scheme unwieldy.

By January 1982, Mr. Hertzfeld started engaged on software program for the Macintosh, maybe the pc’s most distinctive function, which he referred to as the user-interface toolbox.

The toolbox was envisioned as a set of software program routines for setting up the home windows, pull-down menus, scroll bars, icons, and different graphic objects within the Macintosh working system. Since RAM house could be scarce on the Macintosh (it initially was to have solely 64 kilobytes), the toolbox routines have been to be part of the Macintosh’s working software program; they might use the Quickdraw routines and function in ROM.

It was vital nonetheless, to not handicap purposes programmers—who may enhance gross sales of the Macintosh by writing applications for it—by proscribing them to only some toolbox routines in ROM. So the toolbox code was designed to fetch definition capabilities—routines that use Quickdraw to create a graphic picture similar to a window—from both the programs disk or an purposes disk. In this fashion, an purposes programmer may add definition capabilities for a program, which Apple may incorporate in later variations the Macintosh by modifying the system disk. “We were nervous about putting (the toolbox) in ROM,” recalled Mr. Hertzfeld, “We knew that after the Macintosh was out, programmers would want to add to the toolbox routines.”

Although the consumer may function just one purposes program at a time, he may switch textual content or graphics from one purposes program to a different with a toolbox routine referred to as scrapbook. Since the scrapbook and the remainder of the toolbox routines have been positioned in ROM, they might run together with purposes applications, giving the phantasm of multitasking. The consumer would minimize textual content from one program into the scrapbook, shut this system, open one other, and paste the textual content from the scrapbook. Other routines within the toolbox, such because the calculator, may additionally function concurrently with purposes applications.

Late within the design of the Macintosh software program, the designers realized that, to market the Macintosh in non-English-speaking nations, a simple manner of translating textual content in applications into overseas languages was wanted. Thus pc code and knowledge have been separated within the software program to permit translation with out unraveling a posh pc program, by scanning the info portion of a program. No programmer could be wanted for translation.

Placing an Early Bet on the 68000 Chip

The 68000, with a 16-bit knowledge bus and 32-bit inner registers and a 7.83-megahertz clock, may seize knowledge in comparatively massive chunks. Mr. Smith allotted with separate controllers for the mouse, the disk drives, and different peripheral capabilities. “We were able to leverage off slave devices,” Mr. Smith defined, “and we had enough throughput to deal with those devices in a way that appeared concurrent to the user.”

When Mr. Smith recommended implementing the mouse with out a separate controller, a number of members of the design workforce argued that if the primary microprocessor was interrupted every time the mouse was moved, the motion of the cursor on the display screen would all the time lag. Only when Mr. Smith received the prototype up and working have been they satisfied it will work.

Likewise, within the second prototype, the disk drives have been managed by the primary microprocessor. “In other computers,” Mr. Smith famous, “the disk controller is a brick wall between the disk and the CPU, and you end up with a poor-performance, expensive disk that you can lose control of. It’s like buying a brand-new car complete with a chauffeur who insists on driving everywhere.

The 68000 was assigned many duties of the disk controller and was linked with a disk-controller circuit built by Mr. Wozniak for the Apple II. “Instead of a wimpy little 8-bit microprocessor out there, we have this incredible 68000—it’s the world’s best disk controller,” Mr. Smith mentioned.

Direct-memory-access circuitry was designed to permit the video display screen to share RAM with the 68000. Thus the 68000 would have entry to RAM at half pace through the dwell portion of the horizontal line of the video display screen and at full pace through the horizontal and vertical retrace. [See diagram, below.]

The 68000 microprocessor, which has unique entry to the read-only reminiscence of the Macintosh, fetches instructions from ROM at full pace—.83 megahertz. The 68000 shares the random-access reminiscence with the video and sound circuitry, accessing RAM solely a part of the time [A]; it fetches directions from RAM at a mean pace of about 6 megahertz. The video and sound directions are loaded immediately into the video-shift register or the sound-counter, respectively. Much of the “glue” circuitry of the Macintosh is contained in eight programmable-array-logic chips. The Macintosh’s capacity to play 4 impartial voices was added comparatively late within the design, when it was realized that a lot of the circuitry wanted already existed within the video circuitry [B]. The 4 voices are added in software program and the digital samples saved in reminiscence. During the video retrace, sound knowledge is fed into the sound buffer.

While constructing the following prototype, Mr. Smith noticed a number of methods to avoid wasting on digital circuitry and improve the execution pace of the Macintosh. The 68000 instruction set allowed Mr. Smith to embed subroutines in ROM. Since the 68000 has unique use of the handle and knowledge buses of the ROM, it has entry to the ROM routines at as much as the total clock pace. The ROM serves considerably as a high-speed cache reminiscence. While constructing the following prototype, Mr. Smith noticed a number of methods to avoid wasting on digital circuitry and improve the execution pace of the Macintosh. The 68000 instruction set allowed Mr. Smith to embed subroutines in ROM. Since the 68000 has unique use of the handle and knowledge buses of the ROM, it has entry to the ROM routines at as much as the total clock pace. The ROM serves considerably as a high-speed cache reminiscence.

The subsequent main revision within the authentic idea of the Macintosh was made within the pc’s show. Mr. Raskin had proposed a pc that may very well be hooked as much as a regular tv set. However, it turned clear early on that the decision of tv show was too coarse for the Macintosh. After a little bit of analysis, the designers discovered they might improve the show decision from 256 by 256 dots to 384 by 256 dots by together with a show with the pc. This added to the estimated worth of the Macintosh, however the designers thought of it an affordable tradeoff.

To maintain the components depend low, the 2 enter/output ports of the Macintosh have been to be serial. The choice to go together with this was a critical one, for the reason that future usefulness of the pc depended largely on its effectivity when hooked as much as printers, local-area networks, and different peripherals. In the early phases of improvement, the Macintosh was not supposed to be a enterprise product, which might have made networking a excessive precedence.

“We had an image problem. We wore T-shirts and blue jeans with holes in the knees, and we had a maniacal conviction that we were right about the Macintosh, and that put some people off.”

—Chris Espinosa

The key issue within the choice to make use of one high-speed serial port was the introduction within the spring of 1981 of the Zilog Corp.’s 85530 serial-communications controller, a single chip to exchange two inexpensive standard components—” vanilla” chips—within the Macintosh. The dangers in utilizing the Zilog chip have been that it had not been confirmed within the area and it was costly, virtually $9 apiece. In addition, Apple had a tough time convincing Zilog that it severely supposed to order the half in excessive volumes for the Macintosh.

“We had an image problem,” defined Mr. Espinosa. “We wore T-shirts and blue jeans with holes in the knees, and we had a maniacal conviction that we were right about the Macintosh, and that put some people off. Also, Apple hadn’t yet sold a million Apple IIs. How were we to convince them that we would sell a million Macs?”

In the top, Apple received a dedication from Zilog to produce the half, which Mr. Espinosa attributes to the negotiating skills of Mr. Jobs. The serial enter/output ports “gave us essentially the same bandwidth that a memory-mapped parallel port would,” Mr. Smith mentioned. Peripherals have been related to serial ports in a daisy-chain configuration with the Apple bus community.

Designing the Mac’s Factory Without the Product

In the autumn of 1981, as Mr. Smith labored on the fourth Macintosh prototype, the design for the Macintosh manufacturing facility was getting beneath manner. Mr. Jobs employed Debi Coleman, who was then working as monetary supervisor at Hewlett-Packard Co. in Cupertino, Calif., to deal with the funds of the Macintosh undertaking. A graduate of Stanford University with a grasp’s diploma in enterprise advertministration, Ms. Coleman was a member of a process drive at HP that was learning factories, high quality administration, and stock administration. This was good coaching for Apple, for Mr. Jobs was intent on utilizing such ideas to construct a extremely automated manufacturing plant for the Macintosh within the United States.

Briefly he thought of constructing the plant in Texas, however for the reason that designers have been to work intently with the manufacturing workforce within the later phases of the Macintosh design, he determined to find the plant at Fremont, Calif., lower than a half-hour’s drive from Apple’s Cupertino headquarters.

Mr. Jobs and different members of the Macintosh workforce made frequent excursions of automated crops in varied industries, significantly in Japan. At lengthy conferences held after the visits, the manufacturing group mentioned whether or not to borrow sure strategies that they had noticed.

The Macintosh manufacturing facility borrowed meeting concepts from different pc crops and different industries. A way of testing the brightness of cathode-ray tubes was borrowed from tv producers.

The Macintosh manufacturing facility design was based mostly on two main ideas. The first was “just-in-time” stock, calling for distributors to ship components for the Macintosh steadily, in small heaps, to keep away from extreme dealing with of parts on the manufacturing facility and scale back injury and storage prices. The second idea was zero-defect components, with any defect on the manufacturing line instantly traced to its supply and rectified to stop recurrence of the error.

The manufacturing facility, which was to churn out a few half million Macintosh computer systems a yr (the quantity stored rising), was designed to be inbuilt three phases: first, outfitted with stations for staff to insert some Macintosh parts, delivered to them by easy robots; second, with robots to insert parts as an alternative of staff; and third, a few years sooner or later, with “integrated” automation, requiring just about no human operators. In constructing the manufacturing facility, “Steve was willing to chuck all the traditional ideas about manufacturing and the relationship between design and manufacturing,” Ms. Coleman famous. “He was willing to spend whatever it cost to experiment in this factory. We planned to have a major revision every two years.”

By late 1982, earlier than Mr. Smith had designed the ultimate Macintosh prototype, the designs of a lot of the manufacturing facility’s main subassemblies have been frozen, and the meeting stations may very well be designed. About 85 % of the parts on the digital-logic printed-circuit board have been to be inserted mechanically, and the remaining 15 % have been to be surface-mounted gadgets inserted manually at first and by robots within the second stage of the manufacturing facility. The manufacturing traces for automated insertion have been laid out to be versatile; the variety of stations was not outlined till trial runs have been made. The materials-delivery system, designed with the assistance of engineers recruited from Texas Instruments in Dallas, Texas, divided small and enormous components between receiving doorways on the supplies distribution middle. The completed Macintoshes coming down the conveyor belt have been to be wrapped in plastic and stuffed into containers utilizing tools tailored from machines used within the wine {industry} for packaging bottles.

Most of the discrete parts within the Macintosh are inserted mechanically into the printed-circuit boards.

As manufacturing facility building progressed, stress constructed on the Macintosh design workforce to ship a closing prototype. The designers had been working lengthy hours however with no deadline set for the pc’s introduction. That modified in the midst of 1981, after Mr. Jobs imposed a troublesome and generally unrealistic schedule, reminding the workforce repeatedly that “real artists ship” a completed product. In late 1981, when IBM introduced its private pc, the Macintosh advertising workers started to check with a “window of opportunity” that made it pressing to get the Macintosh to clients.

“We had been saying, ‘We’re going to finish in six months’ for two years,” Mr. Hertzfeld recalled.

The new urgency led to a collection of design issues that appeared to threaten the Macintosh dream.

The Mac Team Faces Impossible Deadlines

The pc’s circuit density was one bottleneck. Mr. Smith had hassle paring sufficient circuitry off his first two prototypes to squeeze them onto one logic board. In addition, he wanted quicker circuitry for the Macintosh show. The horizontal decision was solely 384 dots—not sufficient room for the 80 characters of textual content wanted for the Macintosh to compete as a phrase processor. One recommended answer was to make use of the word-processing software program to permit an 80-character line to be seen by horizontal scrolling. However, most traditional pc shows have been able to holding 80 characters, and the transportable computer systems with much less functionality have been very inconvenient to make use of.

Another drawback with the Macintosh show was its restricted dot density. Although the analog circuitry, which was being designed by Apple engineer George Crow, accommodated 512 dots on the horizontal axis, Mr. Smith’s digital circuitry—which consisted of bipolar logic arrays—didn’t function quick sufficient to generate the dots. Faster bipolar circuitry was thought of however rejected due to its high-power dissipation and its value. Mr. Smith may consider however one different: mix the video and different miscellaneous circuitry on a single customized n-channel MOS chip.

Mr. Smith started designing such a chip in February 1982. During the following six months the scale of the hypothetical chip stored rising. Mr. Jobs set a transport goal of May 1983 for the Macintosh however, with a backlog of different design issues, Burrell Smith nonetheless had not completed designing the customized chip, which was named after him: the IBM (Integrated Burrell Machine) chip.

Meanwhile, the Macintosh workplaces have been moved from Texaco Towers to extra spacious quarters on the Apple headquarters, for the reason that Macintosh workers had swelled to about 40. One of the brand new staff was Robert Belleville, whose earlier employer was the Xerox Palo Alto Research Corp. At Xerox he had designed the {hardware} for the Star workstation—which, with its home windows, icons. and mouse, is likely to be thought of an early prototype of the Macintosh. When Mr. Jobs provided him a spot on the Macintosh workforce, Mr. Belleville was impatiently ready for authorization from Xerox to proceed on a undertaking he had proposed that was just like the Macintosh—a low-cost model of the Star.

Asthe brand new head of the Macintosh engineering, Mr. Belleville confronted the duty of directing Mr. Smith, who was continuing on what appeared an increasing number of like a dead-end course. Despite the looming deadlines, Mr. Belleville tried a soft-sell strategy.

“I asked Burrell if he really needed the custom chip,” Mr. Belleville recalled. “He said yes. I told him to think about trying something else.”

After excited about the issue for 3 months, Mr. Smith concluded in July 1982 that “the difference in size between this chip and the state of Rhode Island is not very great.” He then got down to design the circuitry with higher-speed programmable-array logic—as he had began to do six months earlier. He had assumed that greater decision within the horizontal video required a quicker clock pace. But he realized that he may obtain the identical impact with intelligent use of quicker bipolar-logic chips that had grow to be accessible only some months earlier. By including a number of excessive-speed logic circuits and some abnormal circuits, he pushed the decision as much as 512 dots.

Another benefit was that the PALs have been a mature expertise and their electrical parameters may tolerate massive variations from the desired values, making the Macintosh extra steady and extra dependable—vital traits for a so-called equipment product. Since {the electrical} traits of every built-in circuit could range from these of different ICs made in numerous batches, the sum of the variances of fiftyor so parts in a pc could also be massive sufficient to threaten the system’s integrity.

“It became an intense and almost religious argument about the purity of the system’s design versus the user’s freedom to configure the system as he liked. We had weeks of argument over whether to add a few pennies to the cost of the machine.”

—Chris Espinosa

Even as late because the summer season of 1982, with one deadline after one other blown, the Macintosh designers have been discovering methods of including options to the pc. After the workforce disagreed over the selection of a white background for the video with black characters or the extra typical white-on-black, it was recommended that each choices be made accessible to the consumer by way of a change on the again of the Macintosh. But this compromise led to debates about different questions.

“It became an intense and almost religious argument,” recalled Mr. Espinosa, “about the purity of the system’s design versus the user’s freedom to configure the system as he liked. We had weeks of argument over whether to add a few pennies to the cost of the machine.”

The designers, being dedicated to the Macintosh, usually labored lengthy hours to refine the system. A programmer may spend many evening hours to scale back the time wanted to format a disk from three minutes to at least one. The reasoning was that expenditure of a Macintosh programmer’s time amounted to little as compared with a discount of two minutes within the formatting time. “If you take two extra minutes per user, times a million people, times 50 disks to format, that’s a lot of the world’s time,” Mr. Espinosa defined.

But if the group’s dedication to refinements usually stored them from assembly deadlines, it paid off in tangible design enhancements. “There was a lot of competition for doing something very bright and creative and amazing,” mentioned Mr. Espinosa. “People were so bright that it became a contest to astonish them.”

The Macintosh workforce’s strategy to working—“like a Chautauqua, with daylong affairs where people would sit and talk about how they were going to do this or that’”—sparked inventive excited about the Macintosh’s capabilities. When a programmer and a {hardware} designer began to debate the way to implement the sound generator, as an example, they have been joined by certainly one of a number of nontechnical members of the workforce—advertising workers, finance specialists, secretaries—who remarked how a lot enjoyable it will be if the Macintosh may sound 4 distinct voices directly so the consumer may program it to play music. That chance excited the programmer and the {hardware} engineer sufficient to spend further hours in designing a sound generator with 4 voices.

The payoff of such discussions with nontechnical workforce members, Mr. Espinosa mentioned, “was coming up with all those glaringly evident things that only somebody completely ignorant could come up with. If you immerse yourself in a group that doesn’t know the technical limitations, then you get a group mania to try and deny those limitations. You start trying to do the impossible—and once in a while succeeding.”

Nobody had even thought of designing a four-voice [sound] generator—that’s, not till “group mania” set in.

The sound generator within the authentic Macintosh was fairly easy—a one-bit register related to a speaker. To vibrate the speaker, the programmer wrote a software program loop that modified the worth of the register from one to zero repeatedly. Nobody had even thought of designing a four-voice generator—that’s, not till “group mania” set in.

Mr. Smith was pondering this drawback when he observed that the video circuitry was similar to the sound-generator circuitry. Since the video was bit-mapped, a little bit of reminiscence represented one dot on the video display screen. The bits that made up an entire video picture have been held in a block of RAM and fetched by a scanning circuit to generate the picture. Sound circuitry required comparable scanning, with knowledge in reminiscence similar to the amplitude and frequency of the sound emanating from the speaker. Mr. Smith reasoned that by including a pulse-width-modulator circuit, the video circuitry may very well be used to generate sound over the last microsecond of the horizontal retrace—the time it took the electron beam within the cathode-ray tube of the show to maneuver from the final dot on every line to the primary dot of the following line. During the retrace the video-scanning circuitry jumped to a block of reminiscence earmarked for the amplitude worth of the sound wave, fetched bytes, deposited them in a buffer that fed the sound generator, after which jumped again to the video reminiscence in time for the following hint. The sound generator was merely a digital-to-analog converter related to a linear amplifier.

To allow the sound generator to supply 4 distinct voices, software program routines have been written and embedded in ROM to simply accept values representing 4 separate sound waves and convert them into one complicated wave. Thus a programmer writing purposes applications for the Macintosh may specify individually every voice with out worrying concerning the nature of the complicated wave.

Gearing as much as Build Macs

In the autumn of 1982, because the manufacturing facility was being constructed and the design of the Macintosh was approaching its closing kind, Mr. Jobs started to play a higher function within the day-to-day actions of the designers. Although the {hardware} for the sound generator had been designed, the software program to allow the pc to make sounds had not but been written by Mr. Hertzfeld, who thought of different components of the Macintosh software program extra pressing. Mr. Jobs had been informed that the sound generator could be spectacular, with the analog circuitry and the speaker having been upgraded to accommodate 4 voices. But since this was an extra {hardware} expense, with no audible outcomes at that time, one Friday Mr. Jobs issued an ultimatum: “If I don’t hear sound out of this thing by Monday morning, we’re ripping out the amplifier.”

That motivation despatched Mr. Hertzfeld to the workplace through the weekend to write down the software program. By Sunday afternoon solely three voices have been working. He telephoned his colleague Mr. Smith and requested him to cease by and assist optimize the software program.

“Do you mean to tell me you’re using subroutines!” Burrell Smith exclaimed after analyzing the issue. “No wonder you can’t get four voices. Subroutines are much too slow.”

“Do you mean to tell me you’re using subroutines!” Mr. Smith exclaimed after analyzing the issue. “No wonder you can’t get four voices. Subroutines are much too slow.”

By Monday morning, the pair had written the microcode applications to supply outcomes that happy Mr. Jobs.

Although Mr. Jobs’s enter was generally onerous to outline, his intuition for outlining the Macintosh as a product was vital to its success, in line with the designers. “He would say, ‘This isn’t what I want. I don’t know what I want, but this isn’t it.’” Mr. Smith mentioned.

“He knows what great products are,” famous Mr. Hertzfeld. “He intuitively knows what people want.’’

One example was the design of the Macintosh casing, when clay models were made to demonstrate various possibilities. “I could hardly tell the difference between two models,” Mr. Hertzfeld mentioned. “Steve would walk in and say, ‘This one stinks and this one is great.’ And he was usually right.”

Because Mr. Jobs positioned nice emphasis on packaging the Macintosh to occupy little house on a desk, a vertical design was used, with the disk drive positioned beneath the CRT.

Mr. Jobs additionally decreed that the Macintosh comprise no followers, which he had tried to remove from the unique Apple pc. A vent was added to the Macintosh casing to permit cool air to enter and take up warmth from the vertical energy provide, with scorching air escaping on the prime. The logic board was horizontally positioned.

[Steve] Jobs at instances gave unworkable orders. When he demanded that the designers reposition the RAM chips on an early printed-circuit board as a result of they have been too shut collectively, “most people chortled.”

Mr. Jobs, nonetheless, at instances gave unworkable orders. When he demanded that the designers reposition the RAM chips on an early printed-circuit board as a result of they have been too shut collectively, “most people chortled,” one designer mentioned. The board was redesigned with the chips farther aside, nevertheless it didn’t work as a result of the alerts from the chips took too lengthy to propagate over the elevated distance. The board was redesigned once more to maneuver the chips again to their authentic place.

Stopping the Radiation Leaks

When the design group began to focus on manufacturing, essentially the most imposing process was stopping radiation from leaking from the Macintosh’s plastic casing. At one time the destiny of the Apple II had hung within the steadiness as its designers tried unsuccessfully to satisfy the emissions requirements of the Federal Communications Commission. “I quickly saw the number of Apple II components double when several inductors and about 50 capacitors were added to the printed-circuit boards,” Mr. Smith recalled. With the Macintosh, nonetheless, he continued, “we eliminated all of the discrete electronics by going to a connector-less and solder-less design; we had had our noses rubbed in the FCC regulations, and we knew how important that was.’’ The highspeed serial I/O ports caused little interference because they were easy to shield.

Another question that arose toward the end of the design was the means of testing the Macintosh. In line with the zero-defect concept, the Macintosh team devised software for factory workers to use in debugging faults in the printed-circuit boards, as well as self-testing routines for the Macintosh itself.

The disk controller is tested with the video circuits. Video signals sent into the disk controller are read by the microprocessor. “We can display on the screen the pattern we were supposed to receive and the pattern we did receive when reading off the disk,” Mr. Smith defined, “and other kinds of prepared information about errors and where they occurred on the disk.’’

To test the printed-circuit boards in the factory, the Macintosh engineers designed software for a custom bed-of-nails tester that checks each computer in only a few seconds, faster than off-the-shelf testers. If a board fails when a factory worker places it on the tester, the board is handed to another worker who runs a diagnostic test on it. A third worker repairs the board and returns it to the production line.

Each Macintosh is burned in—that is, turned on and heated—to detect the potential for early failures before shipping, thus increasing the reliability of the computers that are in fact shipped.

When Apple completed building the Macintosh factory, at an investment of $20 million, the design team spent most of its time there, helping the manufacturing engineers get the production lines moving. Problems with the disk drives in the middle of 1983 required Mr. Smith to redesign his final prototype twice.

Some of the plans for the factory proved troublesome, according to Ms. Coleman. The automatic insertion scheme for discrete components was unexpectedly difficult to implement. Many of the precise specifications for the geometric and electrical properties of the parts had to be reworked several times. Machines proved to be needed to align many of the parts before they were inserted. Although the machines, at $2000 apiece, were not expensive, they were a last-minute requirement.

The factory had few major difficulties with its first experimental run in December 1983, although the project had slipped from its May 1983 deadline. Often the factory would stop completely while engineers busily traced the faults to the sources—part of the zero-defect approach. Mr. Smith and the other design engineers virtually lived in the factory that December.

In January 1984 the first salable Macintosh computer rolled off the line. Although the production rate was erratic at first, it has since settled at one Macintosh every 27 seconds—about a half million a year.

An Unheard of $30 Million Marketing Budget

The marketing of the Macintosh shaped up much like the marketing of a new shampoo or soft drink, according to Mike Murray, who was hired in 1982 as the third member of the Macintosh marketing staff. “If Pepsi has two times more shelf space than Coke,” he defined, “you will sell more Pepsi. We want to create shelf space in your mind for the Macintosh.’’

To create that space on a shelf already crowded by IBM, Tandy, and other computer companies, Apple launched an aggressive advertising campaign—its most expensive ever.

Mr. Murray proposed the first formal marketing budget for the Macintosh in late 1983: he asked for $40 million. “People literally laughed at me,” he recalled. “They said, ‘What kind of a yo-yo is this guy?’ “He didn’t get his $40 million budget, but he got close to it—$30 million.

“We’ve established a beachhead with the Macintosh. If IBM knew in their heart of hearts how aggressive and driven we are, they would push us off the beach right now.”

—Mike Murray

The advertising marketing campaign began earlier than the Macintosh was launched. Television viewers watching the Super Bowl soccer sport in January 1984 noticed a industrial with the Macintosh overcoming Orwell’s nightmare imaginative and prescient of 1984.

Other tv commercials, in addition to journal and billboard adverts, depicted the Macintosh as being straightforward to study to make use of. In some adverts, the Mac was positioned immediately alongside IBM’s private pc. Elaborate shade foldouts in main magazines pictured the Macintosh and members of the design workforce.

“The interesting thing about this business,” mused Mr. Murray, “is that there is no such thing as a historical past. The greatest manner is to come back in actually good, actually perceive the basics of the expertise and the way the software program sellers work, after which run as quick as you may.’’

The Mac Team Disperses

“We’ve established a beachhead with the Macintosh,” defined Mr. Murray. “We’re on the beach. If IBM knew in their heart of hearts how aggressive and driven we are, they would push us off the beach right now, and I think they’re trying. The next 18 to 24 months is do-or-die time for us.”

With gross sales of the Lisa workstation disappointing, Apple is relying on the Macintosh to outlive. The capacity to convey out a profitable household of merchandise is seen as a key to that purpose, and the corporate is engaged on a collection of Macintosh peripherals—printers, local-area networks, and the like. This, too, is proving each a technical and organizational problem.

“Once you go from a stand-alone system to a networked one, the complexity increases enormously,” famous Mr. Murray. “We cannot throw it all out into the market and let people tell us what is wrong with it. We have to walk before we can run.”

Only two software program applications have been written by Apple for the Macintosh—Macpaint, which permits customers to attract footage with the mouse, and Macwrite, a word-processing program. Apple is relying on impartial software program distributors to write down and market purposes applications for the Macintosh that can make it a extra enticing product for potential clients. The firm can also be modifying some Lisa software program to be used on Macintosh and making variations of the Macintosh software program to run on the Lisa.

Meanwhile the small, coherent Macintosh design workforce is not. “Nowadays we’re a large company,” Mr. Smith remarked.

“The pendulum of the project swings,” defined Mr. Hertzfeld, who has taken a go away of absence from Apple. “Now the company is a more mainstream organization, with managers who have managers working for them. That’s why I’m not there, because I got spoiled” engaged on the Macintosh design workforce.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

[ad_2]