[ad_1]

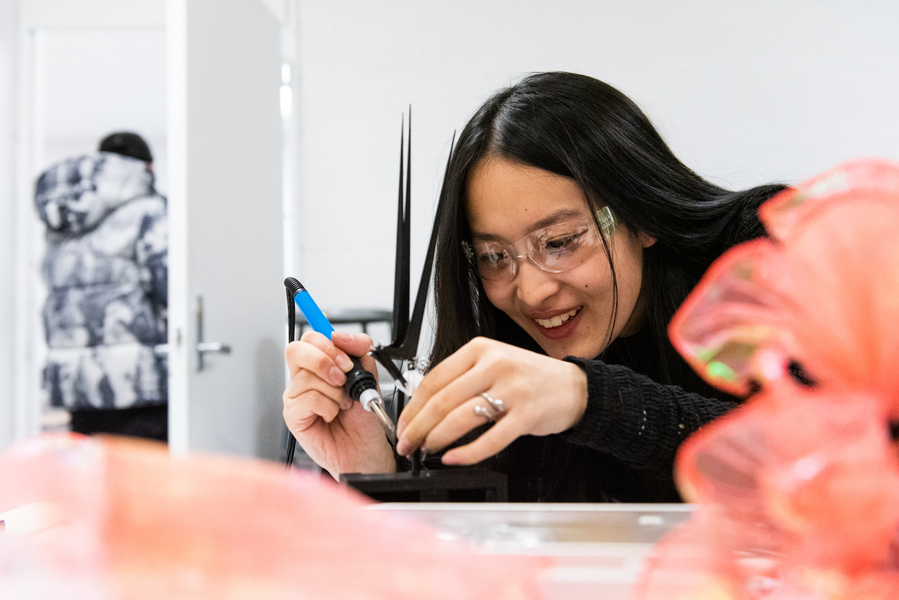

Shua Cho works on her art work in “Introduction to Physical Computing for Artists” on the MIT Student Art Association. Photo: Sarah Bastille

By Ken Shulman | Arts at MIT

One pupil confesses that motors have all the time freaked them out. Amy Huynh, a first-year pupil within the MIT Technology and Policy Program, says “I just didn’t respond to the way electrical engineering and coding is usually taught.”

Huynh and her fellow college students discovered a special method to grasp coding and circuits throughout the Independent Activities Period course Introduction to Physical Computing for Artists — a category created by Student Art Association (SAA) teacher Timothy Lee and provided for the primary time final January. During the four-week course, college students realized to make use of circuits, wiring, motors, sensors, and shows by creating their very own kinetic artworks.

“It’s a different approach to learning about art, and about circuits,” says Lee, who joined the SAA educational employees final June after finishing his MFA at Goldsmiths, University of London. “Some classes can push the technology too quickly. Here we try to take away the obstacles to learning, to create a collaborative environment, and to frame the technology in the broader concept of making an artwork. For many students, it’s a very effective way to learn.”

Lee graduated from Wesleyan University with three concurrent majors in neuroscience, biology, and studio artwork. “I didn’t have a lot of free time,” says Lee, who initially supposed to attend medical faculty earlier than deciding to observe his ardour for making artwork. “But I benefited from studying both science and art. Just as I almost always benefited from learning from my peers. I draw on both of those experiences in designing and teaching this class.”

On this January night, the third of 4 scheduled courses, Lee leads his college students by way of an train to create an MVP — a minimal viable product of their artwork mission. The MVP, he explains, serves as an artist’s proof of idea. “This is the smallest single unit that can demonstrate that your project is doable,” he says. “That you have the bare-minimum functioning hardware and software that shows your project can be scalable to your vision. Our work here is different from pure robotics or pure electronics. Here, the technology and the coding don’t need to be perfect. They need to support your aesthetic and conceptual goals. And here, these things can also be fun.”

Lee distributes varied digital objects to the scholars in accordance with their particular wants — wires, soldering irons, resistors, servo motors, and Arduino parts. The college students have already acquired a working information of coding and the Arduino language within the first two class periods. Sophomore Shua Cho is designing a night robe bedecked with flowers that may open and shut repeatedly. Her MVP is a cluster of three blossoms, mounted on a single publish that, when raised and lowered, opens and closes the sewn blossoms. She asks Lee for assist in attaching a servo motor — an digital motor that alternates between 0, 90, and 180 levels — to the publish. Two different college students, engaged on comparable issues, instantly pull their chairs beside Cho and Lee to hitch the dialogue.

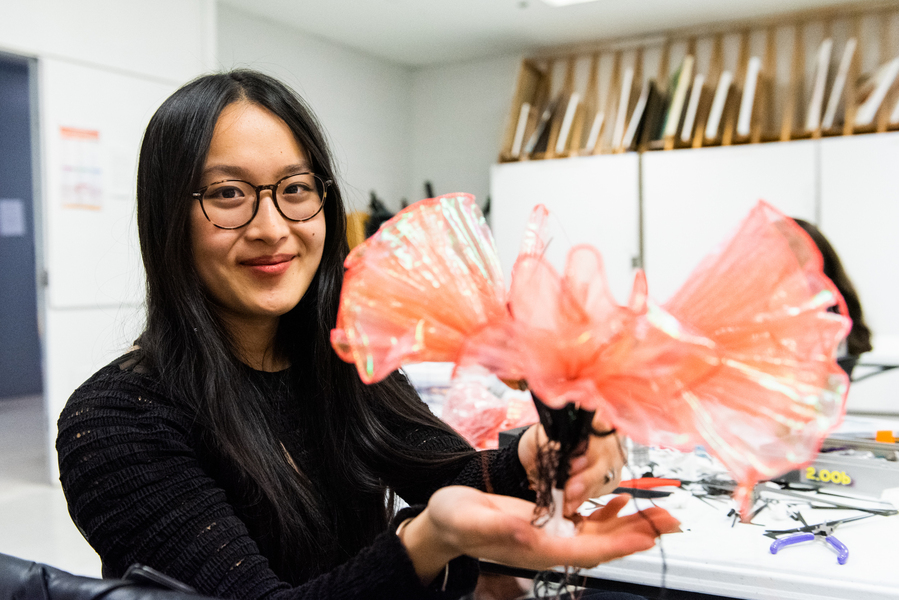

Shua Cho is designing a night robe bedecked with flowers that may open and shut repeatedly. Her minimal viable product is a cluster of three blossoms, mounted on a single publish that, when raised and lowered, opens and closes the sewn blossoms. Photo: Sarah Bastille

The teacher suggests they observe the dynamics of an old style practice locomotive wheel. One pupil calls up the picture on their laptop computer. Then, as a bunch, they attain an answer for Cho — an meeting of wire and glue that may connect the servo engine to the central publish, opening and shutting the blossoms. It’s improvised, even inelegant. But it really works, and proves that the mission for the blossom-covered kinetic gown is viable.

“This is one of the things I love about MIT,” says aeronautical and astronautical engineering senior Hannah Munguia. Her mission is a pair of palms that, when triggered by a movement sensor, will applaud when anybody walks by. “People raise their hand when they don’t understand something. And other people come to help. The students here trust each other, and are willing to collaborate.”

Student Hannah Munguia (left), teacher Timothy Lee (middle), and pupil Bryan Medina work on art work in “Introduction to Physical Computing for Artists” on the MIT Student Art Association. Photo: Sarah Bastille

Cho, who enjoys exploring the intersection between style and engineering, found Lee’s work on Instagram lengthy earlier than she determined to enroll at MIT. “And now I have the chance to study with him,” says Cho, who works at Infinite — MIT’s style journal — and takes courses in each mechanical engineering and design. “I find that having a creative project like this one, with a goal in mind, is the best way for me to learn. I feel like it reinforces my neural pathways, and I know it helps me retain information. I find myself walking down the street or in my room, thinking about possible solutions for this gown. It never feels like work.”

For Lee, who studied computational artwork throughout his grasp’s program, his course is already a profitable experiment. He’d like to supply a full-length model of “Introduction to Physical Computing for Artists” throughout the faculty 12 months. With 10 periods as an alternative of 4, he says, college students would be capable of full their initiatives, as an alternative of stopping at an MVP.

“Prior to coming to MIT, I’d only taught at art institutions,” says Lee. “Here, I needed to revise my focus, to redefine the value of art education for students who most likely were not going to pursue art as a profession. For me, the new definition was selecting a group of skills that are necessary in making this type of art, but that can also be applied to other areas and fields. Skills like sensitivity to materials, tactile dexterity, and abstract thinking. Why not learn these skills in an atmosphere that is experimental, visually based, sometimes a little uncomfortable. And why not learn that you don’t need to be an artist to make art. You just have to be excited about it.”

MIT News