[ad_1]

Fran Caffrey/AFP/Getty Images

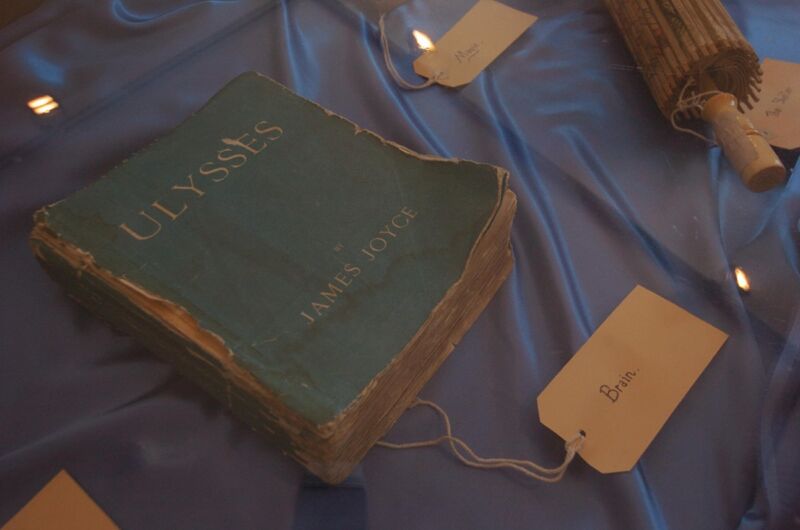

Ulysses, the groundbreaking modernist novel by James Joyce, marked its 100-year anniversary final 12 months; it was first printed on February 2, 1922. The poet T.S Eliot declared the novel to be “crucial expression which the current age has discovered,” and Ulysses has amassed many different followers within the ages since. Count Harry Manos, an English professor at Los Angeles City College, amongst these followers. Manos can be a fan of physics—a lot so, that he penned a December 2021 paper printed in The Physics Teacher, detailing how Joyce had sprinkled a number of examples of classical physics all through the novel.

“The incontrovertible fact that Ulysses comprises a lot classical physics shouldn’t be shocking,” Manos wrote. “Joyce’s buddy Eugene Jolas noticed: ‘the vary of topics he [Joyce] loved discussing was a large one … [including] sure sciences, notably physics, geometry, and arithmetic.’ Knowing physics can improve everybody’s understanding of this novel and enrich its leisure worth. Ulysses exemplifies what physics college students (science and non-science majors) and physics lecturers ought to understand, particularly, physics and literature aren’t mutually unique.”

Ulysses chronicles the lifetime of an strange Dublin man named Leopold Bloom over the course of a single day: June 16, 1904 (now celebrated world wide as Bloomsday). While the novel may look like unstructured and chaotic, Joyce modeled his narrative on Homer’s epic poem the Odyssey; its 18 “episodes” loosely correspond to the 24 books in Homer’s epic. Bloom represents Odysseus; his spouse Molly Bloom corresponds to Penelope; and aspiring author Stephen Daedalus—the primary character of Joyce’s semi-autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916)—represents Telemachus, son of Odysseus and Penelope.

In his paper, Manos notes that the fictional Bloom fancies himself a person accustomed to science, however Joyce slyly reveals his protagonist to be a dilettante whose information stems primarily from the favored science books accessible on the time—which will surely clarify sure misconceptions Bloom holds. For occasion, when Bloom invitations Dedalus to his residence, he tries to impress the younger man by declaring that it’s potential to see the Milky Way throughout the day if the observer have been “positioned on the decrease finish of a cylindrical vertical shaft 5000 ft [sic] deep sunk from the floor in direction of the middle of the Earth.”

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone/Getty Images

This is fake, in fact; Manos writes that Rayleigh scattering would render the celebs invisible—even from the underside of a cylindrical vertical shaft or tall chimney. Where may Bloom have acquired this false impression? Manos notes that Sir Robert Ball, on the time director of the Dunsink Observatory simply north of Dublin, had printed two well-liked books. Dedalus spots one among them, The Story of the Heavens, in Blooms’s library, The different was known as Star-Land, which talks about with the ability to see stars in daylight from the underside of a mineshaft or tall chimney. If Bloom possessed the primary guide, it is extremely seemingly he would even have learn Star-Land—therefore his false impression.

Other physics examples mirror the accepted science of that point, regardless that subsequent advances rendered that science incorrect. For occasion, Bloom ruminates on how warmth is transferred by means of convection, conduction, and radiation whereas boiling water for tea, together with a point out of how the Sun’s radiant warmth is “transmitted by means of omnipresent luminiferous diathermanous ether.” At the time, some physicists nonetheless believed within the existence of a luminiferous ether that served because the medium by means of which gentle traveled. It was finally disproved—due to the well-known Michelson-Morley experiment in 1887 and Albert Einstein’s growth of particular relativity and his paper on the photoelectric impact in 1905 (his annus mirabilis). But Manos notes {that a} highschool textbook up to date with the novel’s 1904 setting nonetheless referenced the ether as a scientific truth.

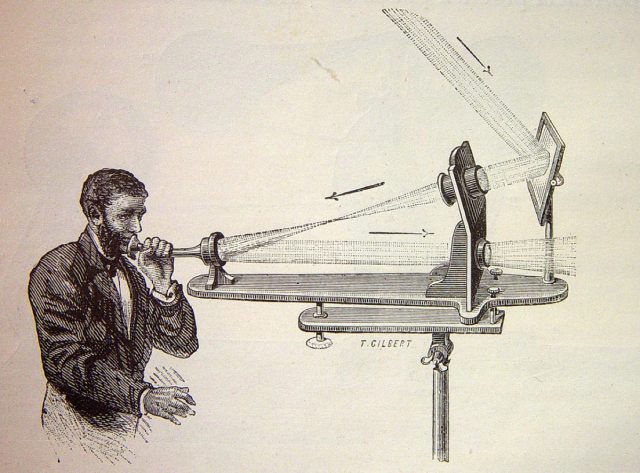

In Chapter 15 (“Circe”), one of many characters says, “You can name me up by sunphone any previous time”—a phrase that additionally seems in Joyce’s handwritten notes for the chapter. While Manos was unable to hint a selected supply for this time period, there was an analogous gadget that had been invented some 20 years earlier: Alexander Graham Bell’s photophone, co-invented together with his assistant Charles Sumner Tainter.

Public area

Unlike the phone, which depends on electrical energy, the photophone transmitted sound on a beam of sunshine. Bell’s voice was projected by means of the instrument to a mirror, inflicting comparable vibrations within the mirror. When he directed daylight into the mirror, it captured and projected the mirror’s vibrations by way of reflection, which have been then remodeled again into sound on the receiving finish of the projection. Bell’s gadget by no means discovered fast software, however it’s arguably the progenitor to trendy fiber optic telecommunications.

There are a number of different situations of physics (each right and incorrect/outdated) talked about in Ulysses, per Manos, together with Bloom misunderstanding the science of x-rays; his confusion over parallax; making an attempt to determine the supply of buoyancy within the Dead Sea; ruminating on Archimedes’ “burning glass”; seeing rainbow colours in a water spray; and pondering why he hears the ocean when he locations a seashell to his ear. Manos believes introducing literature like Ulysses into physics programs might be a boon for non-majors, in addition to encouraging physics and engineering college students to study extra about literature.

In truth, Manos notes that an earlier 1995 paper launched a helpful introductory physics downside involving distance, velocity and time. Ulysses opens with Stephen Dedalus and his roommate, Buck Mulligan, standing on the Martello tower overlooking a bay at Sandy Cove. Mulligan is shaving and slyly performs an “obvious miracle”: he whistles, and some moments later a passing mailboat whistles again. Mulligan had noticed the mailboat by means of his shaving mirror giving its normal two blasts at the moment of the morning, a couple of mile away.

Using a easy equation (t = d/v), “Students can simply calculate that on the velocity of sunshine, Mulligan would have seen the steam in 5.4 ×10-6 s, with the whistle blast,” Manos wrote. “At 1100 ft/s, the sound would have traversed the mile to the Martello tower in 4.8 s, giving Mulligan time to whistle to the heavens and wait (“paused”) for the heavens (the mailboat’s departure whistle) to answer, thus pulling off his obvious miracle.”

DOI: The Physics Teacher, 2021. 10.1119/5.0028832 (About DOIs).