[ad_1]

It took me a second to register the sound of scattered hissing on the Tocqueville Conversations—a two-day “taboo-free discussion” amongst public intellectuals concerning the disaster of Western democracies. More than 100 of us had gathered in a big tent arrange beneath the window of Alexis de Tocqueville’s research, on the grounds of the Sixteenth-century Château de Tocqueville, in coastal Normandy. I couldn’t keep in mind listening to an viewers react like this in such a discussion board.

The democratic disaster that the convention sought to handle has many sides: the rise of the authoritarian proper, metastasizing financial inequality, the pressures of local weather change, and extra. But the convention, held in September 2021, had principally narrowed its focus to the American social-justice ideology that’s generally known as “wokeness.” The particular person being hissed at that afternoon was Rokhaya Diallo, a French West African journalist, social-justice activist, and media character in her mid-40s. (In America, she writes for The Washington Post.) Besides me, she was one in every of only a handful of nonwhite audio system and, to my information, the only practising Muslim.

For many people who had come to alternate concepts, the venue felt important. The château, with its ivy-covered partitions and swan-filled pond, lies distant from the intricacies of multicultural life in fashionable democracies. But Tocqueville was, in fact, one of many world’s keenest interpreters of the American experiment. His basic two-volume textual content, Democracy in America, printed in 1835 and 1840, explored the paradoxical nature of a vibrant new multiethnic society, based on the rules of liberty and equality however compromised from the beginning by African slave labor and the theft of Indigenous land. Its creator, whereas discovering a lot to admire, remained skeptical that such highly effective divisions might ever be transcended, as a result of not like in Europe, social rank was written into the bodily options of the nation’s inhabitants.

Many who declare social justice as their final aim insist that America has achieved little to problem Tocqueville’s grim appraisal. In their view, a number of the nation’s cherished beliefs—individualism, freedom of speech, even the Protestant work ethic—are in reality obstacles to fairness, illusions spun by those that have energy with a view to preserve it and maintain the marginalized of their place. The woke left’s method to addressing historic oppression—particularly, prioritizing race and different classes of identification in all kinds of political and institutional selections—has stirred anxieties within the United States. But the issues expressed on the Tocqueville property have been much less about what this phenomenon means for America than what it would imply for France. As the saying goes, when America sneezes, Europe catches a chilly.

The French have lengthy prided themselves on having a system of presidency that doesn’t acknowledge racial or ethnic designations. The thought is to uphold a common imaginative and prescient of what it means to be French, impartial of race, ethnicity, and faith. Even preserving official statistics on race has, because the Holocaust, been impermissible. Recently, nonetheless, and to the alarm of many within the conventional French commentariat, American-style identification politics has piqued the curiosity of a brand new and extra various technology.

And so I’d come to witness a unprecedented alternate—one that may not occur within the U.S. mainstream. Over the course of the convention, audio system had repeatedly debated whether or not what the French have termed le wokisme is a critical concern. A majority of the panelists and viewers members, myself included, had answered kind of within the affirmative. Political group round identification reasonably than ideology is among the finest predictors of civil strife and even civil struggle, in line with an evaluation of violent conflicts by the political scientist Barbara F. Walter. By pitting teams towards each other in a zero-sum energy wrestle—and sorting them on a scale of advantage based mostly on privilege and oppression—wokeness can’t assist however elevate race and ethnicity to an extent that expands prejudice reasonably than decreasing it, within the course of fueling or, at minimal, offering cowl for a violent and harmful majoritarian response. That, not less than, was the prevailing sense of the group.

As the final panel, “Media and Universities: In Need of Reform and Reassessment?,” acquired underneath means, Diallo took the chance to argue the alternative place. Onstage along with her have been a political scientist and two philosophy professors, one in every of whom was the moderator, Perrine Simon-Nahum. Diallo is a well known and polarizing determine in France, a telegenic proponent of identification politics with a big social-media following. She attracts parallels between the French and American criminal-justice programs (one in every of her documentaries is known as From Paris to Ferguson), making the case that institutional racism afflicts her nation simply because it does the U.S., most notably in discriminatory stop-and-frisk policing. Her views would hardly be thought-about excessive in America, however right here she is seen in some quarters as a genuinely subversive agent.

Simon-Nahum opened the dialog with the query “How can we shape citizens in a democracy?” And what function ought to instructional establishments and the media play? Were woke forces in universities and media striving to delegitimize elites, she continued, and to undermine the establishments of data manufacturing? Were they “building a new totalitarianism of thought?” The woke perfect of disseminating information “on an egalitarian platform,” she recommended, was neither attainable nor even fascinating.

“The circulation of knowledge is also the circulation of experiences,” Diallo responded. “Some minority experiences may be more visible” now because of social media. That poses a much-needed problem to conventional “elite” information manufacturing, which, she stated, had “filtered out” sure views up to now. This declare was indeniable. Just a few weeks after this convention, Emmanuel Macron would grow to be the primary French president to take part in commemorations of the 1961 bloodbath of Algerian protesters by police in Paris. Most French individuals I do know had by no means encountered this occasion both in class or in conventional media.

The woke “have discovered new epistemologies,” Jean-François Braunstein, a philosophy professor at Panthéon-Sorbonne University, nonetheless retorted—theories of data that validate emotions over info. He referred to as Diallo’s place “a staunch attack against science and against truth.” He appeared to wish to develop the dialog’s scope past racial identification to embody the dissolution of the gender binary, which was not a topic Diallo had been addressing. Simon-Nahum demurred however recommended that the bigger disagreement about “the conception of knowledge” was nonetheless worrying; it justified fears that the French discourse was changing into Americanized.

Diallo replied that most individuals in attendance have been seemingly “privileged,” and as such, disproportionately frightened of the “emergence of minority speech [from] people who indeed didn’t have access to certain clubs … and are questioning things that were considered” unquestionable.

“Of course we cannot experience what others experience,” Simon-Nahum responded, with seeming irritation—now not moderating however totally getting into the talk. And but, we are able to perceive it: “It’s called empathy,” she stated, earlier than sharply taking challenge with Diallo’s level about privilege.

It was round that point, with Diallo remoted from the remainder of the panel, that I began to note the hissing, coming from the viewers when she spoke. As the moderator refused to concede even the theoretical risk that any information will be derived from identification, I observed Diallo’s expression rising distant. Simon-Nahum pressed on, referring to Diallo’s attraction to lived expertise as not solely misguided however a form of “domination.” “This intellectual war that’s being waged is a threat to democracy,” she stated. “I feel threatened … first and foremost [as] a citizen.”

Braunstein chimed in to say that Diallo’s argument reminded him of a quote by the extravagantly racist author and Nazi collaborator Charles Maurras: “A Jew can never understand [Jean] Racine, because he’s not French!” (When Diallo objected, Braunstein stated that he was not evaluating her to Maurras.)

It went on like that. By the top of the dialogue, I used to be considerably shaken. On many discrete factors, I tended to agree with the philosophers on the panel. I’ve made Paris my house for the previous 11 years and have been elevating French kids there for 9 of them, which is to say I really feel a real stake within the tradition. I’m satisfied that it will be a horrible, maybe even insurmountable, loss to desert the universalist, color-blind French perfect to the fractured panorama of American tribal identification.

And but I additionally felt that one thing essentially unfair had simply transpired. France, like America, is consistently evolving. Any try to make sense of it must take Diallo’s arguments critically. She had tried to share an understanding of French life—one wherein rising segments of the French inhabitants really feel excluded and censured—that her interlocutors couldn’t or wouldn’t settle for, however that their conduct appeared to substantiate.

I had till that time thought-about Diallo an ideological opponent. She had likewise regarded me warily—as a privileged, nonwhite, non-French spokesperson for a universalism that masks white prerogatives. Her private credo of kinds, “Kiffe ta race” (“Love your race”), which is the title of her podcast and her most up-to-date guide, immediately contradicts my very own writing towards the reinforcement of racial identification. And but, when she walked offstage alone, I discovered myself speeding to meet up with her. As we spoke, to my shock, my eyes turned teary. I wished her to know that I had seen what she’d skilled, even when nobody else had. “That happens all the time here,” she advised me. “It happens all the time.”

The French response to le wokisme has been revelatory for me. I’m engaged on a guide concerning the methods American tradition and establishments modified after the summer time of 2020, and the way that transformation has, to an uncommon diploma, reverberated internationally, and notably in France. The incident on the Tocqueville convention brought about me to recalibrate a few of my assumptions—and to understand extra keenly simply how simply anti-wokeness can succumb to a dogmatism as inflexible because the one it seeks to oppose. Many of the debates right here happen as if in a parallel universe, eerily acquainted however with a number of illuminating variations. They are a helpful prism for considering the excesses and limitations, in addition to the deserves, of the social-justice fervor that has gripped the United States.

The French left exerts far much less energy than American progressives do over the media, academia, tradition, and elite firms. Diversity as an finish in itself, and minority illustration specifically, continues to be removed from a mainstream preoccupation right here. Outside one prestigious faculty—Sciences Po, in Paris—affirmative motion scarcely exists. Perhaps due to comparatively muscular labor legal guidelines (which Macron has sought to weaken), individuals don’t concern being canceled for controversial speech, both in universities or within the office. The #MeToo motion couldn’t acquire a lot traction in a rustic whose main left-leaning intellectuals and not less than one newspaper printed unequivocal defenses of pedophilia as not too long ago because the Nineteen Seventies. France has little persistence for American culture-war staples corresponding to genderless pronouns and loos. Even the comparatively modest, gender-neutral iel was forcefully dismissed by the primary woman, Brigitte Macron: “Our language is beautiful. And two pronouns is enough,” she has stated, to virtually no pushback in any respect.

So why has the response to American-style identification politics grow to be so heated throughout the French mental sphere?

One motive lies in an important distinction between the political realities of France and the United States. In France, the controversy over le wokisme is sort of at all times a proxy for a deeper concern about Islam and terror on the European continent. Those seen as permissive of wokeness are presumed to be indulging not merely a sufferer advanced, however one thing way more sinister: islamo-gauchisme, what the far-right former presidential candidate Marine Le Pen has described because the alliance between Islamist fanatics and the French left. My pal Pascal Bruckner, a historically liberal thinker, describes it in his guide The Tyranny of Guilt as “the fusion between the atheist far Left and religious radicalism.” This is known as a wedding of comfort: The anti-capitalist left sees Islam’s potential for fomenting unrest as a device to discredit the middle and radically remake bourgeois society; reactionary Muslim events, in flip, faux to affix the left in opposing racism and globalization as a way of amassing energy.

Thus, within the French racial creativeness, it’s the doubtlessly violent Muslim—not merely the person with darkish pores and skin—who represents the final word “other.” But even when France didn’t expertise violence, an identification politics that may give cowl to separatism is seen as unacceptable. This is what Simon-Nahum appears to have meant when she stated she felt “threatened” as a citizen. And it’s why, for some, issues as trivial as halal-food aisles within the grocery store tackle an existential high quality that has no actual equal in Twenty first-century America.

But France’s vehement response to wokeism has one other trigger, which is barely discernible within the U.S. It has to do with France’s advanced relationship with America itself.

On September 13, 2001, beside a picture of the Statue of Liberty shrouded in blooming clouds of smoke, the entrance web page of Le Monde proudly declared, “Nous sommes tous Américains.” It was a grand and heartfelt gesture of solidarity within the face of incomprehensible hatred and barbarity, one which was returned in 2015 when a spasm of terror swept over France. That extraordinary yr started with the bloodbath by al-Qaeda-affiliated militants of 12 individuals within the Paris places of work of the satirical journal Charlie Hebdo, which had republished caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad. It concluded with a citywide rampage in November, wherein 130 have been slain and lots of extra have been injured in cafés, eating places, and the Bataclan live performance corridor—most of them by homegrown radicals declaring allegiance to the Islamic State. The rapid outpouring of grief within the American press, and the tens of millions of Facebook profile footage filtered with the tricolor, was as transferring because it was justified.

Over the subsequent 5 years, the U.S. might now not muster such empathy. By the autumn of 2020, America had totally turned its gaze inward. The police killings of George Floyd and others directed America’s consideration to its personal legacy of slavery and racism. These have been the situations wherein a brand new and at occasions totalizing ideology, organized round a racial binary, gained traction. And virtually in a single day, the mainstream American press turned reluctant to view what had been taking place in France (particularly, a spree of machete assaults, decapitations, and stabbings, from Paris all the way down to the Riviera) via the lens of particular person company, ideology, non secular radicalism, terrorism, and even plain previous good and evil. Suddenly, it was all about identification and programs of oppression. Through the lens of racial reckoning, fanatically secular and color-blind France had, in a way, introduced this grief upon itself.

For many in France, a headline in The New York Times crystallized this new angle of reproach. Following the beheading of a middle-school instructor named Samuel Paty in October 2020—for the transgression of exhibiting these Charlie Hebdo cartoons within the classroom—the American newspaper of document’s first encapsulation of the assault targeted not on Paty however on his assailant: “French Police Shoot and Kill Man After a Fatal Knife Attack on the Street.” The headline was subsequently modified, and the article itself was comparatively balanced. But when it described Paty as having “incited anger among some Muslim families,” the implication to many French readers was unambiguous: Teaching the common worth of free speech to all college students, no matter ethnic affiliation, was what had actually led to Paty’s homicide. French audiences took this concept—which was echoed all through a lot of the American media—as an exoneration of Paty’s murderer, an 18-year-old Chechen asylum recipient with extremist beliefs who had hunted down his sufferer solely after studying of his existence from a social-media mob.

Reading such protection within the American press was painful for a lot of French individuals of all ethnicities and spiritual affiliations. For months, the perceived abandonment by an admired and influential ally was the topic of fixed dialog. Why have been American commentators utilizing Paty’s killing to attain factors on Twitter by condemning a society they didn’t know? Why had the Times framed this act of savagery as a easy—and, one may infer, probably extreme—police taking pictures? Why have been journalists at different outlets, together with The Washington Post, reinforcing a story that decreased advanced problems with secularism, republicanism, and immigration to broad allegations of Islamophobia? Why have been critics on social media resorting to the blunt racial catchall of whiteness? Did they not perceive that French residents of African or Arab descent have been additionally appalled by such violence?

Many French individuals started to see their nation as a pivotal theater of resistance to woke orthodoxy. Macron himself turned a decided critic, insisting that his nation comply with its personal path to attain a multiethnic democracy, with out mimicking the identity-obsessed American mannequin. “We have left the intellectual debate to … Anglo-Saxon traditions based on a different history, which is not ours,” he argued simply earlier than Paty’s killing, in his October 2020 speech towards “Islamist separatism.” Macron’s minister of nationwide schooling on the time, Jean-Michel Blanquer, spoke of the necessity to wage “a battle” towards the woke concepts being promulgated by American universities.

The unease with le wokisme in France, then, is formed and heightened by the nation’s distinctive historical past and self-perception—its respectable fears of homegrown jihad and its issues about domineering Yankee affect. You can’t perceive the French response to wokeness with out understanding these home preoccupations. But on the similar time, you possibly can’t dismiss France’s extra philosophical—and universalist—critiques of wokeism merely due to them. The battle towards wokeness that Blanquer described has been joined on each side of the Atlantic. Last spring, I visited him at his places of work to get his perspective on it.

Blanquer, the minister of nationwide schooling from 2017 till May 2022, has been one in every of France’s most constant, controversial, and highly effective opponents of woke ideology. (He as soon as filed a go well with—later dismissed—towards a French academics’ union for utilizing the time period institutional racism in an outline of its workshops.) In January 2022, he spoke at—and, by his presence, lent the state’s imprimatur to—a colloquium on the Sorbonne titled “After Deconstruction,” which introduced collectively an array of critics of the brand new social-justice orthodoxy.

Blanquer is matter-of-fact and unsparing. While finding out at Harvard within the ’90s, he advised me, he first turned conscious of PC tradition, the precursor to what he sees as at present’s disaster. He sympathized with most of the goals of political correctness however grew cautious of its software: Treating ladies and minority teams as completely different and particular, he started to suppose, was in the end antithetical to equality. “In the history of ideas, it’s not the first time that, when you push an idea to the extreme, it becomes the contrary,” he stated.

He has some extent. Especially when turbocharged by social media, wokeness tends to fetishize identification and bestow ethical authority on complete teams by dint of historic oppression. Of the numerous cheap issues one may need with this method, most are dismissed by its proponents as brute racism, undeserving of significant engagement. But within the Ministry of National Education’s foyer sat a big faculty portrait of the late Samuel Paty—a literal martyr to the results of zealous group identification.

The key to wholesome and sustainable social progress is knowing to what extent a doubtlessly helpful thought will be pursued earlier than tipping over into self-defeating extremism. A relentless lure for would-be guardians of the liberal order is a response that itself turns into excessive. As Mathieu Lefevre of More in Common, a nonprofit working in France and elsewhere to reunite divided societies, defined to me, wokeness “rearranges [all] the chairs at the ideological dinner party.” On the one aspect, it fosters a form of leftist illiberalism that’s virtually non secular in nature, in that it brooks no dissent—the kind of ideology that center-left liberals have traditionally opposed. And on the opposite aspect, “being anti-woke allows a proximity between the center and the far right. You start with a [colloquium] about le wokisme, and you end up questioning foundational liberal principles like freedom of expression.” You find yourself banning phrases corresponding to institutional racism.

This isn’t merely a theoretical pitfall for the French center-left and center-right. In 2021, then–Minister of Higher Education Frédérique Vidal ordered a authorities investigation into public-university analysis that sought “to divide and fracture”—in different phrases, analysis specializing in colonialism and racial distinction. The establishment tasked with finishing up the investigation ultimately refused to take action, however because the sociologist François Dubet wrote in Le Monde, “How can we think that it is up to the State to say which currents of thought are acceptable and which are not?”

What’s extra, a critic may notice, Blanquer’s inflexible devotion to the precept of universalism entails a sure blindness to typically legitimate minority issues—a couple of lack of recognition, inclusion, and dignity. Though there aren’t any official statistics on the matter, in line with a 2016 French research, younger people who find themselves perceived as Black and Arab are 20 occasions extra seemingly than everybody else to be stopped by the cops. In November 2020, a video went viral exhibiting the unprovoked pummeling of a Black music producer by armed police in Paris. I, too, in the end consider in universalism, and I fear that obsessively monitoring demographic variations can lead us to ascribe practically something to racism. But occasions like this have lent credence to the identitarian left’s argument that addressing unequal therapy is sort of unimaginable when you possibly can’t measure it.

And so the activists and people listening to them have seemed to America for a vocabulary to precise what is occurring in their very own nation, whether or not or not that vocabulary totally is smart right here. Wokeism’s perpetual, typically performative outrage; its lack of nuance; its reflexive inclination to silence dissent—these are critical flaws for individuals who care about liberal democracy. And but these similar qualities have attracted good-faith consideration to points too lengthy uncared for in America, and sometimes nonetheless unmentionable in Europe.

When I requested Blanquer why he had recommended up to now that the battle towards wokeness was already misplaced, he admitted that it was solely “a provocation—I never think we’ll lose.” And after I requested him whether or not there are particular circumstances of cancel tradition in France that evaluate to essentially the most egregious circumstances within the U.S., he paused. Eventually, he talked about a manufacturing of The Suppliants, by Aeschylus. In 2019, there have been protests over the forged’s use of darkish make-up. But these protests have been comparatively small and in the end unsuccessful. When I attended the opening-night efficiency, the minister of tradition was there to point out solidarity towards the tried censorship. In a typical debate in America, this might be the second when the declare is made—falsely—that cancel tradition doesn’t exist.

In 2010, the U.S. State Department invited French politicians and activists to a management program to assist them strengthen the voice and illustration of ethnic teams which were excluded from authorities. Rokhaya Diallo attended, which a lot of her critics nonetheless use as proof that she is a educated proselytizer of American social-justice propaganda. (In 2017, underneath strain from each the left and the correct, Macron’s authorities requested for her removing—as Diallo put it to me, it “canceled” her—from a authorities advisory council, seemingly on the grounds that race- and religious-based political organizing contradicts key rules of French republicanism and secularism, or laïcité.)

But in a categorized memo printed on WikiLeaks, former U.S. Ambassador Charles H. Rivkin laid out the pragmatic, self-interested rationale for this system, a part of what was referred to as a “Minority Engagement Strategy”:

French establishments haven’t confirmed themselves versatile sufficient to regulate to an more and more heterodox demography. We consider that if France, over the long term, doesn’t efficiently improve alternative and supply real political illustration for its minority populations, France might grow to be a weaker, extra divided nation, maybe extra crisis-prone and inward-looking, and consequently a much less succesful ally.

Today, in a post-Trump America, it’s unimaginable to learn such an evaluation with out a sense of deep embarrassment. Still, I used to be haunted by these phrases as I watched the French elections final spring. Macron was reelected, however the outcomes clearly confirmed that an identity-driven illiberalism lengthy lively on the correct is gaining pressure on the left: Both the far left and much proper gained seats in Parliament. Significant numbers of minority voters—feeling ignored and misunderstood—have grown sufficiently demoralized to surrender on the middle. After being changed in May as minister of nationwide schooling, Blanquer ran for Parliament and didn’t even survive the primary spherical of elections final June—coming in third behind candidates at every excessive.

Many within the French mainstream are right to notice that wokeness is philosophically incoherent—attempting to finish racism by elevating race—and, if taken far sufficient, harmful. The politics of identification that undergirds the obsession with social justice obliterates individuality. It subordinates human psychology—at all times an ambiguous terrain—to sweeping platitudes and self-certain dictates; it bins all of us in. Worst of all, it smacks of determinism, trapping the current in a unending previous that steals the innocence from any collective future.

Le wokisme has not gone properly in America. Cancel tradition is kind of actual within the U.S., and its results have been poisonous to debate and, in lots of circumstances, to institutional determination making. Resistance to wokeism’s extra formidable designs—the elimination of merit-based screening at elite public excessive faculties; the “defunding” and even abolition of the police—has been widespread and, to many progressives’ shock, ethnically various. Yet its outright suppression in France has not gone properly both. Ambassador Rivkin’s evaluation is relevant to each societies: America and France are concurrently changing into weaker, much less succesful, every undermined by rising inner divisions—the one by overemphasizing them, the opposite by denying them altogether.

I stay satisfied that an authentically color-blind society—one which acknowledges histories of distinction however refuses to fetishize or reproduce them—is the vacation spot we should purpose for. Either we obtain real universalism or we destroy ourselves as a consequence of our mutual resentment and suspicion.

Attempting this can be painful and, at occasions, really feel counterintuitive. Woke impulses are irrepressible at present, and they’ll seemingly stay in order the grand international venture of constructing multicultural democracies continues. The query, then, will not be how one can stamp out these impulses, however how one can channel them responsibly, whereas refusing to succumb to the myopia of group identification. A riff on the apocryphal Winston Churchill quip about liberal ideology describes the problem aptly: You haven’t any head when you wholly embrace it, however when you categorically reject it, you don’t have any coronary heart.

In precept, it’s onerous to disclaim the prevalence of the French mannequin of common citizenship—liberté, égalité, fraternité. Yet in apply, the exhausting and typically disingenuous American reflex to interpret social life via imperfect notions of identification nonetheless manages to understand actual experiences that in any other case get dismissed and, when suppressed lengthy sufficient, put us all in peril. It can be a mistake for both tradition to remake itself solely within the picture of the opposite. The future belongs to the multiethnic society that finds a approach to synthesize them.

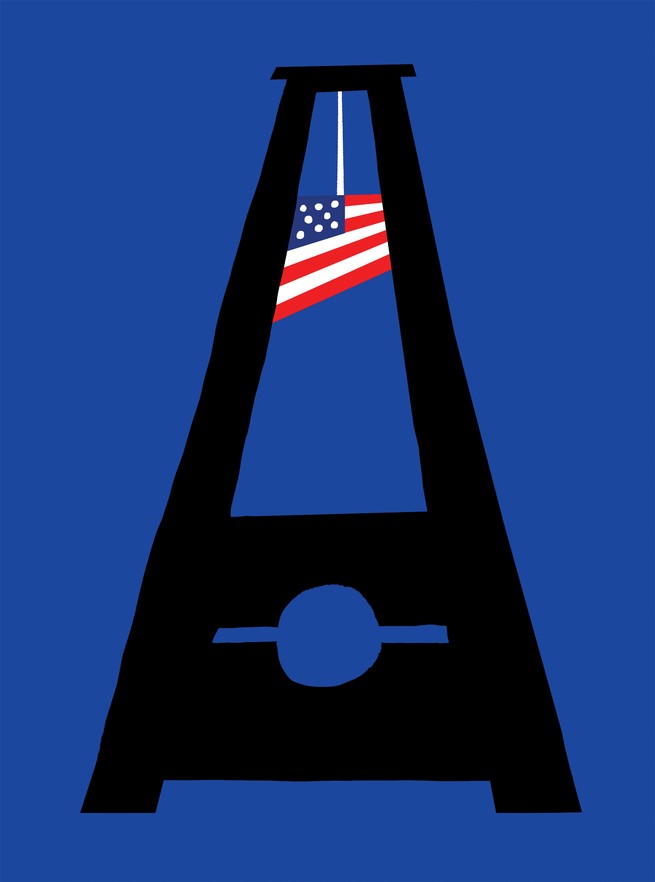

This article seems within the March 2023 print version with the headline “The French Are in a Panic Over le Wokisme.”