[ad_1]

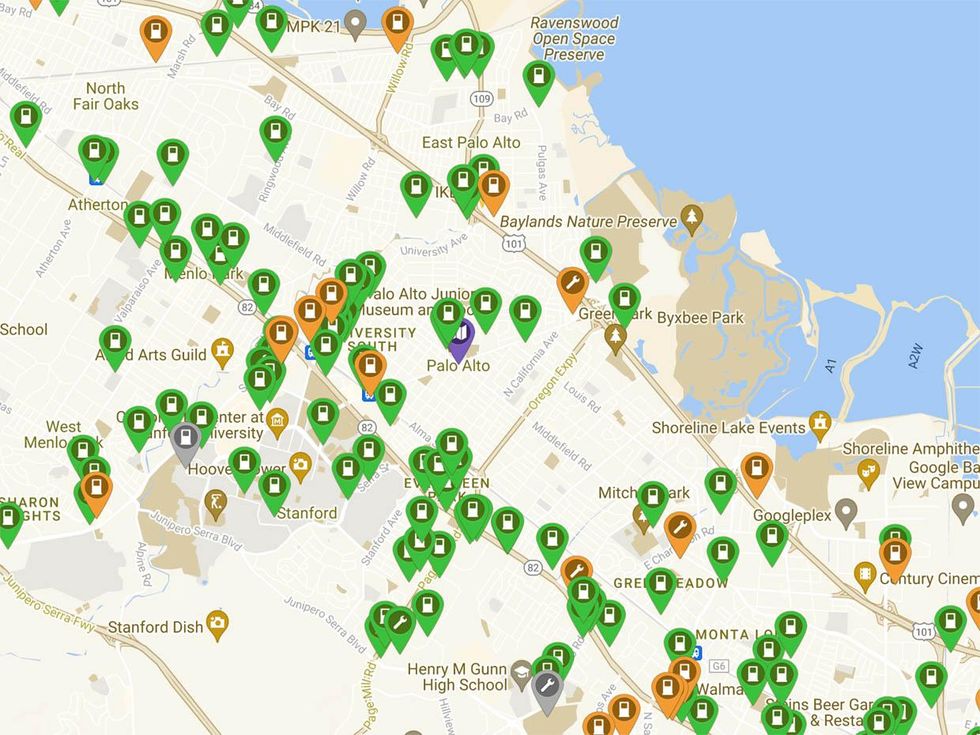

Palo Alto’s authorities has set a really aggressive Sustainability and Climate Action Plan with a purpose of decreasing its greenhouse gasoline emissions to 80 % under the 1990 degree by the 12 months 2030. In comparability, the state’s purpose is to realize this quantity by 2050. To understand this discount, Palo Alto should have 80 % of automobiles inside the subsequent eight years registered in (and commuting into) town be EVs (round 100,000 complete). The projected variety of charging ports might want to develop to an estimated 6,000 to 12,000 public ports (some 300 being DC quick chargers) and 18,000 to 26,000 residential ports, with most of these being L2-type charging ports.

“There are places even today where we can’t even take one more heat pump without having to rebuild the portion of the system. Or we can’t even have one EV charger go in.” —Tomm Marshall

To meet Palo Alto’s 2030 emission-reduction objectives, town, which owns and operates the electrical utility, want to enhance considerably the quantity of native renewable power getting used for electrical energy era (suppose rooftop photo voltaic) together with the flexibility to make use of EVs as distributed-energy assets (vehicle-to-grid (V2G) connections). The metropolis has offered incentives for the acquisition of each EVs and charging ports, the set up of heat-pump water heaters, and the set up of photo voltaic and battery-storage methods.

There are, nonetheless, just a few potholes that should be crammed to fulfill town’s 2030 emission goals. At a February assembly of Palo Alto’s Utilities Advisory Commission, Tomm Marshall, assistant director of utilities, acknowledged, “There are places even today [in the city] where we can’t even take one more heat pump without having to rebuild the portion of the [electrical distribution] system. Or we can’t even have one EV charger go in.”

Peak loading is the first concern. Palo Alto’s electrical-distribution system was constructed for the electrical a great deal of the Nineteen Fifties and Sixties, when family heating, water, and cooking had been operating primarily on pure gasoline. The distribution system doesn’t have the capability to assist EVs and all electrical home equipment at scale, Marshall steered. Further, the system was designed for one-way energy, not for distributed-renewable-energy gadgets sending energy again into the system.

An enormous downside is the three,150 distribution transformers within the metropolis, Marshall indicated. A 2020 electrification-impact research discovered that with out enhancements, greater than 95 % of residential transformers can be overloaded if Palo Alto hits its EV and electrical-appliance targets by 2030.

Palo Alto’s electrical-distribution system wants an entire improve to permit the utility to steadiness peak masses.

For occasion, Marshall acknowledged, it isn’t uncommon for a 37.5 kilovolt-ampere transformer to assist 15 households, because the distribution system was initially designed for every family to attract 2 kilowatts of energy. Converting a gasoline equipment to a warmth pump, for instance, would draw 4 to six kW, whereas an L2 charger for EVs can be 12 to 14 kW. A cluster of uncoordinated L2 charging may create an extreme peak load that may overload or blow out a transformer, particularly when they’re towards the top of their lives, which many already are. Without sensible meters—that’s, Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI), which shall be launched into Palo Alto in 2024—the utility has little to no family peak load insights.

Palo Alto’s electrical-distribution system wants an entire improve to permit the utility to steadiness peak masses, handle two-way energy flows, set up the requisite variety of EV charging ports and electrical home equipment to assist town’s emission-reduction objectives, and ship energy in a protected, dependable, sustainable, and cybersecure method. The system additionally should be capable of cope in a multihour-outage state of affairs, the place future electrical home equipment and EV charging will begin unexpectedly when energy is restored, putting a heavy peak load on the distribution system.

Palo Alto is contemplating investing US $150 million towards modernizing its distribution system, however that can take two to 3 years of planning, in addition to one other three to 4 years or extra to carry out all the required work, however provided that the utility can get the engineering and administration workers, which continues to be briefly provide there and at different utilities throughout the nation. Further, like different industries, the power enterprise has change into digitized, which means the talents wanted are totally different from these beforehand required.

Until it may modernize its distribution community, Marshall conceded that the utility should proceed to cope with offended and confused prospects who’re being inspired by town to put money into EVs, charging ports, and electrical home equipment, solely then to be advised that they is probably not accommodated anytime quickly.

Policy runs up towards engineering actuality

The state of affairs in Palo Alto is not distinctive. There are some 465 cities within the United States with populations between 50,000 and 100,000 residents, and one other 315 which might be bigger, many going through comparable challenges. How many can actually assist a speedy inflow of hundreds of recent EVs? Phoenix, for instance, desires 280,000 EVs plying its streets by 2030, practically seven instances as many because it has at the moment. Similar mismatches between climate-policy needs and an power infrastructure incapable of supporting these insurance policies will play out throughout not solely the United States however elsewhere in a single kind or one other over the following 20 years as conversion to EVs and electrical home equipment strikes to scale.

As in Palo Alto, it is going to probably be blown transformers or continually flickering lights that sign there’s an EV charging-load problem. Professor Deepak Divan, the director of the Center for Distributed Energy at Georgia Tech, says his staff discovered that in residential areas “multiple L2 chargers on one distribution transformer can reduce its life from an expected 30 to 40 years to 3 years.” Given that many of the hundreds of thousands of U.S. transformers are approaching the top of their helpful lives, changing transformers quickly might be a serious and expensive headache for utilities, assuming they’ll get them.

Supplies for distribution transformers are low, and prices have skyrocketed from a spread of $3,000 to $4,000 to $20,000 every. Supporting EVs might require bigger, heavier transformers, which suggests most of the 180 million energy poles on which these want to take a seat will should be changed to assist the extra weight.

Exacerbating the transformer loading downside, Divan says, is that many utilities “have no visibility beyond the substation” into how and when energy is being consumed. His staff surveyed “twenty-nine utilities for detailed voltage data from their AMI systems, and no one had it.”

This state of affairs shouldn’t be true universally. Xcel Energy in Minnesota, for instance, has already began to improve distribution transformers due to potential residential EV electrical-load points. Xcel president Chris Clark advised the Minneapolis Star Tribune that 4 or 5 households shopping for EVs noticeably impacts the transformer load in a neighborhood, with a household shopping for an EV “adding another half of their house.”

Joyce Bodoh, director of power options and clear power for Virginia’s Rappahannock Electric Cooperative (REC), a utility distributor in central Virginia, says that “REC leadership is really, really supportive of electrification, energy efficiency, and electric transportation.” However, she provides, “all those things are not a magic wand. You can’t make all three things happen at the same time without a lot of forward thinking and planning.”

As a part of this planning effort, Bodoh says that REC has actively been performing “an engineering study that looked at line loss across our systems as well as our transformers, and said, ‘If this transformer got one L2 charger, what would happen? If it got two L2s, what would happen, and so on?’” She provides that REC “is trying to do its due diligence, so we don’t get surprised when a cul-de-sac gets a bunch of L2 chargers and there’s a power outage.”

REC additionally has hourly energy-use information from which it may discover the place L2 chargers could also be in use due to the load profile of EV charging. However, Bodoh says, REC doesn’t simply need to know the place the L2 chargers are, but in addition to encourage its EV-owning prospects to cost at nonpeak hours—that’s, 9 p.m. to five a.m. and 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. REC has lately arrange an EV charging pilot program for 200 EV house owners that gives a $7 month-to-month credit score in the event that they do off-peak charging. Whether REC or different utilities can persuade sufficient EV house owners of L2 chargers to persistently cost throughout off-peak hours stays to be seen.

“Multiple L2 chargers on one distribution transformer can reduce its life from an expected 30 to 40 years to 3 years.” —Deepak Divan

Even if EV proprietor habits modifications, off-peak charging might not totally resolve the peak-load downside as soon as EV possession actually ramps up. “Transformers are passively cooled devices,” particularly designed to be cooled at night time, says Divan. “When you change the (power) consumption profile by adding several EVs using L2 chargers at night, that transformer is running hot.” The threat of transformer failure from uncoordinated in a single day charging could also be particularly aggravated throughout instances of summer time warmth waves, an problem that issues Palo Alto’s utility managers.

There are technical options accessible to assist unfold EV charging peak masses, however utilities should make the investments in higher transformers and sensible metering methods, in addition to get regulatory permission to alter electricity-rate constructions to encourage off-peak charging. Vehicle-to-grid (V2G), which permits an EV to function a storage system to easy out grid masses, could also be one other answer, however for many utilities within the United States, this can be a long-term possibility. Numerous points should be addressed, such because the updating of hundreds of thousands of family electrical panels and sensible meters to accommodate V2G, the creation of agreed-upon nationwide technical requirements for the data alternate wanted between EVs and native utilities, the event of V2G regulatory insurance policies, and residential and industrial enterprise fashions, together with honest compensation for using an EV’s saved power.

As power skilled Chris Nelderfamous at a National Academy EV workshop, “vehicle-to-grid is not really a thing, at least not yet. I don’t expect it to be for quite some time until we solve a lot of problems at various utility commissions, state by state, rate by rate.”

In the following article within the sequence, we are going to have a look at the complexities of making an EV charging infrastructure.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web