[ad_1]

This article was first revealed as “Marcian E Hoff.” It appeared within the February 1994 challenge of IEEE Spectrum. A PDF model is obtainable on IEEE Xplore. The pictures appeared within the authentic print model.

But for Hoff, the microprocessor was merely one blip amongst many alongside the tracing of his lengthy fascination with electronics. His ardour for the sector led him from New York City’s used electronics shops to elite college laboratories, by the extreme early years of the microprocessor revolution and the tumult of the online game trade, and in the end to his job in the present day: high-tech non-public eye.

Fairly early in his childhood Hoff found out that one of the simplest ways to really feel much less like a child—and somewhat extra highly effective—was to know how issues work. He began his explorations with chemistry. By the age of 12 he had moved on to electronics, constructing issues with components ordered from an Allied Radio Catalog, a shortwave radio package, and surplus relays and motors salvaged from the rubbish at his father’s employer, General Railway Signal Co., in Rochester, NY. Then in highschool, working largely with secondhand elements, he constructed an oscilloscope, an achievement he parlayed right into a technician’s job at General Railway Signal.

Hoff returned to that job throughout breaks from his undergraduate research at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, N.Y. Several summers started with Hoff getting into the General Railway laboratory to search out the researchers’ two greatest oscilloscopes damaged. He would restore the state-of-the-art Tektronix 545s, then transfer on to extra attention-grabbing stuff, like inventing an audio frequency railroadpractice monitoring circuit and a lightning safety unit that gave him two patents earlier than he was out of his teenagers.

The neatest thing in regards to the job, Hoff recalled, was the entry it gave him to elements that had been past the budgets of most engineering college students within the l950s—transistors, for example, and even the just-introduced energy transistor. He did an undergraduate thesis on transistors used as switches, and the money prize he gained for it shortly went for a Heathkit scope of his personal.

Early Neural Networks

Hoff preferred the engineering programs at Rensselaer, however not the slender focus of the faculty itself. He needed to broaden his perspective, each intellectually and geographically (he had by no means been quite a lot of miles west of Niagara Falls), so selected California’s Stanford University for graduate faculty. While working towards his Ph.D. there, he did analysis in adaptive programs (which in the present day are known as neural networks) and, together with his thesis advisor Bernard Widrow, racked up two extra patents.

“He had a toy train moving back and forth under computer control, balancing a broom stick. I saw him as a kooky inventor, a mad scientist.”

—Stanley Mazor

His Intel colleague Mazor, now coaching supervisor at Synopsys Inc., Mountain View, Calif., recalled assembly Hoff in his Stanford laboratory.

“He had a toy train moving back and forth under computer control, balancing a broomstick,” Mazor stated. “I saw him as a kooky inventor, a mad scientist.”

After getting his diploma, Hoff stayed at Stanford for six extra years as a postdoctoral researcher, persevering with the work on neural networks. At first, his group made the networks trainable through the use of a tool whose resistance modified with the quantity and path of present utilized. It consisted of a pencil lead and a chunk of copper wire sitting in a copper sulfate and sulfuric acid resolution, they usually known as it a memistor.

“One result of all our work on microprocessors that has always pleased me is that we got computers away from those [computer center] people.”

—Ted Hoff

The group quickly acquired an IBM 1620 pc, and Hoff had his first expertise in programming—and in bucking the system. He needed to cope with officers on the campus pc middle who thought all computer systems ought to be in a single place, run by specialists who dealt with the bins of punched playing cards delivered by researchers. The thought {that a} researcher ought to program pc programs interactively was anathema to them.

Ted Hoff: Vital Stats

Name

Marcian E. (Ted) Hoff Jr.

Date of start

Oct. 28, 1937

Family

Wife, Judy; three daughters, Carolyn, Lisa, and Jill

Education

BS, 1958, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, N.Y.; MS, 1959, Ph.D., 1962, Stanford University, California, all in electrical engineering

First job

Planting cabbages

First electronics job

Technician, General Railway Signal Co., Rochester, N.Y.

Biggest shock in profession

Media hysteria over the microprocessor

Patents

17

Books just lately learn

Introduction to Nuclear Reactor Theory by John R. Lamarsh; A Compiler Generator by William M. McKeeman, James J. Horning, and David B. Wortman

People most revered

Intel Corp. founders Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore, Intel chief government officer Andrew Grove

Favorite eating places

Postrio and Bella Voce in San Francisco, Beausejour in Los Altos, Calif.

Favorite motion pictures

2001, Dr. Strangelove

Motto

“If it works, it’s aesthetic”

Leisure actions

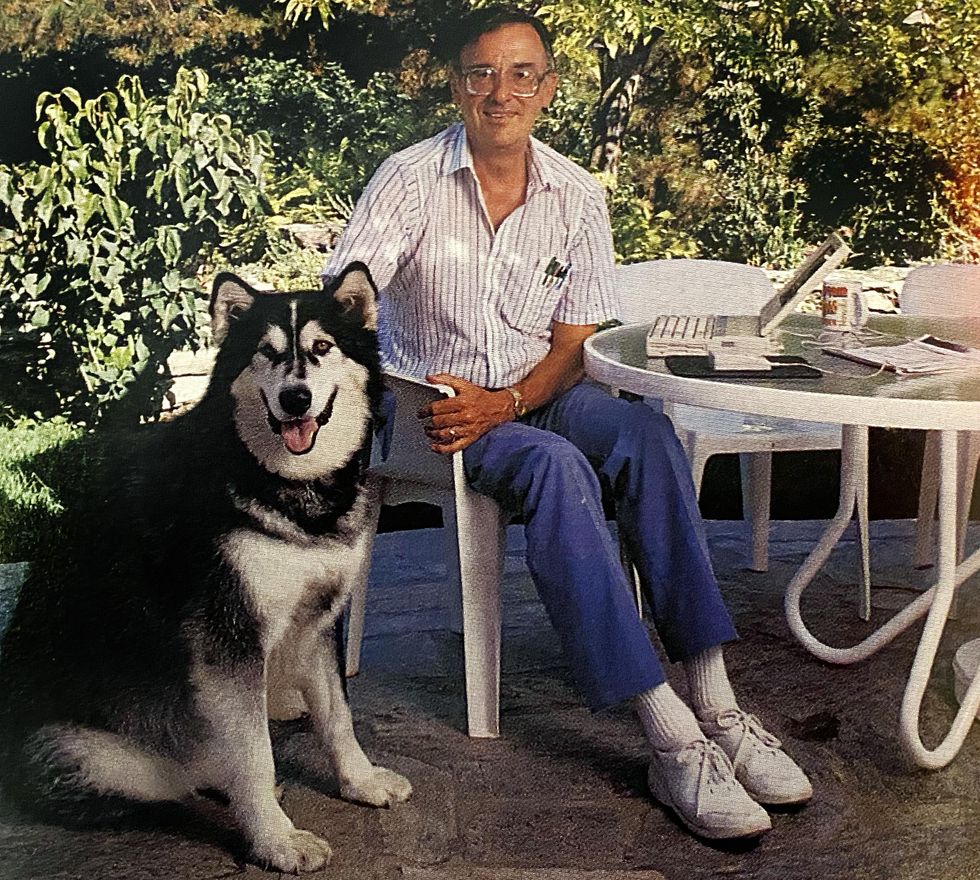

Playing with electronics; attending operas and concert events; going to the theater, physique browsing in Hawaii; strolling his Alaskan malamutes

Car

Porsche 944

Management creed

“The best motivation is self-motivation”

Organizational memberships

IEEE, Sigma Xi

Major awards

Stuart Balantine Medal of the Franklin Institute, IEEE Cledo Brunetti Award, IEEE Centennial Medal, IEEE Fellow

“One result of all our work on microprocessors that has always pleased me,” Hoff instructed IEEE Spectrum, “is that we got computers away from those people.”

By 1968 scholar hostility to the federal government over the Vietnam War was rising and life for researchers on campus who, like Hoff, relied on authorities funding was trying as if it would get uncomfortable. Hoff had already been considering the probabilities of commercial jobs when he obtained a phone name from Robert Noyce, who instructed him he was beginning a brand new firm, Intel Corp., and had heard Hoff is likely to be considering a job. He requested Hoff the place the semiconductor built-in circuit enterprise would discover its subsequent progress space. “Memories,” Hoff replied.

That was the reply Noyce had in thoughts (Intel was launched as a reminiscence producer), and that 12 months he employed Hoff as a member of the technical employees, Intel’s twelfth worker. Working on reminiscence expertise, Hoff quickly obtained a patent for a cell to be used in MOS random-access built-in circuit reminiscence. Moving on to turn into supervisor of functions analysis, he had the primary buyer contact of his profession.

“Engineering people tend to have a very haughty attitude toward marketing, but I discovered you learn a tremendous amount if you keep your eyes and ears open in the field.”

—Hoff

“Engineering people tend to have a very haughty attitude toward marketing,” Hoff stated, “but I discovered you learn a tremendous amount if you keep your eyes and ears open in the field. Trying to understand what problems people are trying to solve is very helpful. People back in the lab who don’t have that contact are working at a disadvantage.”

From 12 Chips to One Microprocessor

One group of consumers with whom Hoff made contact had been from Busicom Corp., Tokyo. Busicom had employed Intel to develop a set of customized chips for a low-cost calculator and had despatched three engineers to Santa Clara to work on the chip designs. Hoff was assigned to take care of them, getting them pencils and paper, displaying them the place the lunchroom was—nothing technical.

But the technical a part of Hoff’s thoughts has no off-switch, and he shortly concluded that the engineers had been going within the flawed path. Twelve chips, every with greater than 3000 transistors and 36 leads, had been to deal with totally different parts of the calculator logic and controls, and he surmised the packaging alone would price greater than the focused retail value of the calculator. Hoff was struck by the complexity of this tiny calculator, in contrast with the simplicity of the PDP-8 minicomputer he was at present utilizing in one other challenge, and he concluded {that a} easy pc that would deal with the capabilities of a calculator may very well be designed with about 1900 transistors. Given Intel’s superior MOS course of, all these, he felt, may match on a single chip.

Marcian E. “Ted” Hoff

The Busicom engineers had little interest in dumping their design in favor of Hoff’s unproved proposal. But Hoff, with Noyce’s blessing, began engaged on the challenge. Soon Mazor, then a analysis engineer at Intel, joined him, and the 2 pursued Hoff’s concepts, creating a easy instruction set that may very well be carried out with about 2000 transistors. They confirmed that the one set of directions may deal with decimal addition, scan a keyboard, keep a show, and carry out different capabilities that had been allotted to separate chips within the Busicom design.

In October 1969, Hoff, Mazor, and the three Japanese engineers met with Busicom administration, visiting from Japan, and described their divergent approaches. Busicom’s managers selected Hoff’s method, partly, Hoff stated, as a result of they understood that the chip may have different functions past that of a calculator. The challenge was given the interior moniker “4004.”

Federico Faggin, now president and chief government officer of Synaptics Inc., San Jose, Calif., was assigned to design the chip, and in 9 months got here up with working prototypes of a 4-bit, 2300-transistor “microprogrammable computer on a chip.” Busicom obtained its first cargo of the units in February 1971.

Faggin recalled that when he started implementing the microprocessor, Hoff appeared to have misplaced curiosity within the challenge, and infrequently interacted with him. Hoff was already engaged on his subsequent challenge, the preliminary design of an 8-bit microprogrammable pc for Computer Terminals Corp., San Antonio, Texas, which, architected by Computer Terminals, was named the 8008. Hoff all the time “had to do very cutting-edge work,” Faggin instructed Spectrum. “I could see a tension in him to always be at the forefront of what was happening.”

In these early Intel days, Mazor recalled that Hoff had numerous concepts for initiatives, lots of which, although not commercially profitable, proved prescient: a RAM chip that will act like a digital digicam and seize a picture in reminiscence, a online game with transferring spaceships, a tool for programming erasable programmable ROMs, and computer-aided design instruments meant for logic simulation.

The Intel advertising division they estimated that gross sales [of microprocessors] may complete solely 2000 chips a 12 months.

Meanwhile, the microprocessor revolution was gearing up, albeit slowly. Hoff joined Faggin as a microprocessor evangelist, attempting to persuade folks that general-purpose one chip computer systems made sense. Hoff stated his hardest promote was to the Intel advertising division.

“They were rather hostile to the idea,” he recalled, for a number of causes. First, they felt that every one the chips Intel may make would go for a number of years to 1 firm, so there was little level in advertising them to others. Second, they instructed Hoff, ‘‘We have diode salesman out there struggling like crazy to sell memories, and you want them to sell computers? You’re loopy.” And lastly, they estimated that gross sales may complete solely 2000 chips a 12 months.

But phrase went out. In May 1971 an article in Datamation journal talked about the product, and the next November Intel produced its first advert for the 4004 CPU and positioned it in Electronic News. By 1972 tales in regards to the miracle of what started being known as the microprocessor began showing commonly within the press, and Intel’s rivals adopted its lead by launching microprocessor merchandise of their very own.

Hoff by no means even thought of patenting the microprocessor. To him the invention appeared to be apparent.

One step Hoff didn’t take at the moment was apply for a patent, although he had already efficiently patented a number of innovations. (Later, with Mazor and Faggin he filed for and was granted a patent for a “memory system for a multi-chip digital computer.”)

Looking again, Hoff recalled that he by no means even thought of patenting the microprocessor in these days. To him the invention appeared to be apparent, and obviousness was thought of grounds for rejecting a patent utility (although, Hoff stated bitterly, the patent workplace at present appears to disregard that rule). It was apparent to Hoff that if in a single 12 months a pc may very well be constructed with 1000 circuits on100 chips, and if within the following 12 months these 1000 circuits may very well be put onto10 chips, ultimately these 1000 circuits may very well be con structed on one chip.

Instead of patenting, Hoff in March 1970 revealed an article within the proceedings of the 1970 IEEE International Convention that acknowledged: “An entirely new approach to design of very small computers is made possible by the vast circuit complexity possible with MOS technology. With from 1000 to 6000 MOS devices per chip, an entire central processor may be fabricated on a single chip.”

But in December 1970, an impartial inventor exterior the cliquish semiconductor trade, Gilbert Hyatt, filed for a patent on a processor and talked about that it was to be made on a single chip. In 1990, after quite a few appeals and extensions, Hyatt was granted that patent and commenced gathering royalties from many microprocessor producers. Currently, although historical past traces in the present day’s microprocessor again to Hoff, Mazor, and Faggin, the authorized rights to the invention belong to Hyatt.

The Invention of the Codec

While the microprocessor has proved to be his most celebrated achievement, Hoff doesn’t view it as his greatest technical breakthrough. That designation he reserves for the single-chip analog-to-digital/ digital-to-analog coder/decoder (codec).

“Now that work was an exciting technical challenge,” Hoff recollected with some glee, “because there were so many who said it couldn’t be done.”

The challenge was kicked off by Noyce, who noticed the phone trade as ripe for brand spanking new expertise, and urged Hoff to search out an vital product for that market. Studying phone communications, Hoff and several other different researchers noticed that digitized voice transmission, then getting used between central workplaces, relied on the usage of complicated costly codecs that tied into electromechanical switches.

”We thought,” Hoff instructed Spectrum, “we could integrate this, the analog-to-digital conversion, on a chip, and then use these circuits as the basis for switching.”

Besides lowering the price of the programs to the phone firm, such chips would allow corporations to construct small department exchanges that dealt with switching electronically.

Hoff and his group developed a multiplexed method to conversion during which a single converter is shared by the transmit and obtain channels. They additionally established numerous different methods for conversion and decoding that Hoff noticed as not being apparent and for which he obtained patents.

With that challenge’s completion in 1980, after six years of effort, and its switch to Intel’s manufacturing facility in Chandler, Ariz., Hoff turned an Intel Fellow, free to pursue no matter expertise him. What him was returning to his work on adaptive buildings, combining the ideas he had wrestled with at Stanford with the facility of the microprocessor within the service of speech recognition. After a 12 months he constructed a recognition system that Intel marketed for a number of years.

A first-rate buyer for the system was the automotive trade. Its inspectors used the programs to assist them take a look at a automobile because it lastly left the meeting line. When an inspector famous out loud numerous issues that wanted fixing, the system would immediate him for additional data, and log his responses in a pc.

From Intel to Atari

Though his place as an Intel Fellow gave Hoff a good quantity of freedom, he discovered himself losing interest. Intel’s success in microprocessors by 1983 had turned it right into a chip provider, and different corporations had been designing the chips into programs.

“I had always been more interested in systems than in chips,” Hoff stated, “and I had been at Intel for 14 years, at a time when the average stay at a company in Silicon Valley was three years. I was overdue for a move.”

Again, Hoff had not gone past enthusiastic about leaving Intel when a brand new job got here to him. Atari Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif., then a booming online game firm owned by Warner Communications Inc. and a significant consumer of microprocessors, was on the lookout for a vice chairman of company expertise. In February 1983, after discussing the scope of the concepts that Atari researchers had been pursuing, Hoff latched onto the chance.

Intel from the beginning had a structured, extremely managed tradition. At Atari, chaos reigned.

Intel from the beginning had a structured, extremely managed tradition. At Atari, chaos reigned. Under Hoff had been analysis laboratories in Sunnyvale, Los Angeles, and Grass Valley, Calif.; Cambridge, Mass.; and New York City. Researchers had been engaged on image telephones, digital aids for joggers, pc controls that gave tactile suggestions, graphical environments akin to in the present day’s digital actuality, digital sound synthesis, superior private computer systems, and software program distribution through FM sidebands.

But Hoff had barely had time to find out about all of the analysis initiatives underneath approach earlier than the online game enterprise took a well-publicized plunge. Without strong inner controls, Atari was unable to find out how effectively its video games had been promoting on the retail level, and distributors had been returning lots of of 1000’s of cartridges and sport machines. Hoff started receiving orders for workers cuts month-to-month.

“It would have been one thing if I had known I had to cut back to, say, one-quarter the size of my group,” he instructed Spectrum. “But when every month you find you have to cut another chunk, morale really drops.”

In July 1984, whereas Hoff was at his thirtieth highschool reunion, Warner bought Atari to Jack Tramiel. Hoff then had to decide on between convincing Tramiel that he may play a task in a narrowly targeted firm bored with funding futuristic analysis, and permitting Warner to purchase out his contract. He selected the latter.

Looking again, most people who had been at Atari in these days now view them darkly. But Hoff recollects his 12 months there as an pleasing and in the end helpful expertise. “Maybe I look at it more positively than I should,” he stated, “but it turned out to be a good transition for me, and the life I have now is a very nice one.”

“Whenever you are working on one problem, there is always another problem over here that seems more interesting.”

—Hoff

He now spends half his time as a marketing consultant and half pursuing technical initiatives of his personal devising—a learnout gadget for machine instruments, numerous forms of body grabbers, sample recognition, and methods for analog-to-digital conversion. This variegated schedule is ideal for him. He has all the time felt himself to be a generalist, and has had hassle specializing in only one expertise.

“It’s easy for me to get distracted,” he stated. “Whenever you are working on one problem, there is always another problem over here that seems more interesting. But now it is more likely that my own projects get delayed, rather than things critical to other people and their employment.”

Faggin for one just isn’t stunned that such impartial work appeals to Hoff. “He never was the gregarious type,” Faggin stated. “He liked introverted work, the thinking, the figuring out of new things. That is what he is good at. I always was impressed how he was able to visualize an architecture for a new IC, practically on the spot.”

“He comes up with idea after idea, situation after situation. I think if he wanted to, Ted could sit down and crank out a patent a month.”

—Gary Summers

Said Gary Summers, president and chief government officer of Teklicon Inc., Mountain View, the consulting agency that employs Hoff in the present day: “He comes up with idea after idea, situation after situation. I think if he wanted to, Ted could sit down and crank out a patent a month.”

“There is no doubt in my mind that he is a genius,” Mazor acknowledged. Summers readily concurred.

Hoff’s first challenge after Atari was a voicemanaged music synthesizer, which gave off the sound of a particular instrument when somebody sang into it. Hoff’s greatest contribution to the challenge was a system that ensured that the rising notes could be in tune, or no less than harmonically complement the tune, even when the singer strayed off key. He scored one other patent for this technique, and the gadget was bought briefly by the Sharper Image catalog, however by no means turned an enormous success.

Hoff nonetheless contributes sometimes to product designs. At Teklicon, nevertheless, the place he’s vice chairman and chief technical officer, most of his consulting is finished for legal professionals. Hoff has a singular mixture of lengthy expertise with digital design and long-standing pack rat habits. His dwelling workshop comprises about eight private computer systems of various makes and vintages, 5 oscilloscopes, together with a classic Tektronix 545 scope, 15000 ICs inventoried and filed, and cabinets loaded with IC information books courting proper again to the Nineteen Sixties.

“If my washing machine breaks down, I call the repairman. Most clever engineers would buy the replacement gear and install it. Ted is capable of analyzing the reason the gear failed in the first place, redesigning a better gear from basic principles, carving it out of wood, casting it at his home, and dynamically balancing it on his lathe before installing it.”

—Mazor

When a lawyer reveals him a patent disclosure, even one many years previous, he can decide whether or not or not it may then have been “reduced to practice” and whether or not it supplied adequate data to permit “one of ordinary skill in the art” to apply the invention. Then he can construct a mannequin proving his conclusion, utilizing classic elements from his assortment, and show the mannequin in court docket as an professional witness. This model-building can get very fundamental. On Spectrum’s go to, Rochelle salt crystals that Hoff tried to develop for a current court docket demonstration littered his workshop flooring, subsequent to metal-working gear that he makes use of to construct circumstances for his fashions.

Hoff sees this means to get right down to fundamentals as one in every of his strengths. “I relate things to fundamental principles,” he stated. “People who don’t question the assumptions made going into a problem often end up solving the wrong problem.”

Mazor stated, “If my washing machine breaks down, I call the repairman. Most clever engineers would buy the replacement gear and install it. Ted is capable of analyzing the reason the gear failed in the first place, redesigning a better gear from basic principles, carving it out of wood, casting it at his home, and dynamically balancing it on his lathe before installing it.”

Doing authorized detective work appeals to Hoff for one more cause: it provides him an excuse to hunt for attention-grabbing “antique” elements at flea markets and electronics shops.

Hoff can’t talk about the specifics of patent circumstances he has been concerned with. Several just lately had been within the online game space; others have concerned numerous IC corporations. In numerous circumstances, Hoff was assured that his aspect was proper, and his aspect nonetheless misplaced, so he felt little shock when the microprocessor patent was granted to Hyatt. (After the award was made, although, he did sit down with Hyatt’s patent utility and tried to design a working microprocessor based mostly on Hyatt’s disclosures. He discovered a number of incongruities—like a clock fee solely suited to bipolar expertise with logic that would solely be rendered in MOS expertise, and logic that required far too many transistors to placed on a chip, proving in his thoughts that the award was incorrect.)

Seeing another person get credit score for the microprocessor, notably in current media experiences, “is irritating,” Hoff instructed Spectrum, “but I’m not going to let it bother me, because I know what I did, I know what all the other people on our project did, and I know what kind of company Intel is. And I know that I was where the action was.”

Editor’s word: Hoff retired from Teklicon in 2007. He at present serves as a decide for the Collegiate Inventors Competition, held yearly by the National Inventors Hall of Fame. These days, his fundamental technical pursuits encompass power, water, and local weather change.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web